Conversant with Cultures

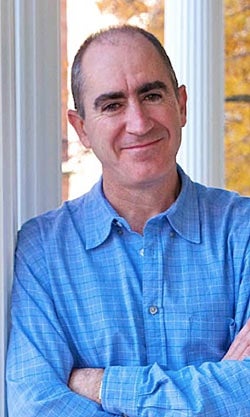

Antonio Candau Becomes Chair of the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures

In many ways, Antonio Candau often reminds his students, learning a new language is an unconscious process. He doesn’t mean that the diligent study of verb forms or grammatical distinctions is unnecessary. But he does insist on the value of simple exposure to a language in its daily uses. Listen to radio and TV broadcasts on your laptops, he tells the students. Spend your junior year abroad. And, since regular practice in speaking is as essential as listening, make the effort to express yourselves even when your ideas outrun your vocabulary.

With this kind of advice, Candau coaches his students through the learning process. And his style is the same whether he is teaching introductory Spanish or one of his advanced courses in literature and culture. Students reading a novel in a foreign language sometimes feel defeated by the sheer number of words they don’t know. So Candau says to them, "You have to use what you do know as steppingstones to try to make as much sense of the text as possible. You have to focus on the path instead of the obstacles."

A Houseful of Languages

Eight years after he began teaching in the College, Candau is now chair of the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures. He and his colleagues occupy most of Guilford House, and given the scope of their programs, that is no surprise. The department offers majors in French, German, Japanese Studies and Spanish; minors in Chinese, Hebrew, Italian and Russian; and courses in Arabic and Portuguese.

Like the college's performing arts programs, modern languages and literatures attracts significant numbers of double majors—students whose primary interests range from biology to political science to management. According to Candau, undergraduates often see an educational or career advantage in mastering a foreign language. Many began their language studies in middle or high school and don't want to abandon what they’ve learned. And many welcome the change of pace that language and literature courses provide. As Candau says of his advanced students, "They’re really happy to step away from the computer and read a book and talk about it in Spanish."

In his seminars on contemporary Spanish literature, Candau often draws on his early memories of places and events to illustrate the texts he is teaching. For him, this isn't just a matter of providing cultural reference points; he feels that he connects with students on a personal level by reconnecting with his past.

Candau was born in Valladolid, a Castilian city northwest of Madrid whose streets, as he remembers them, were always full of people. In his youth, he studied French and German, mostly by conjugating verbs and memorizing rules. Although he realizes "these things are important," he is pleased that language instruction today—across the world, and certainly in his department—focuses more on communication.

When he was in his early 20s, Candau met his future wife, an American college student spending her junior year in Spain. Soon he was taking English classes and building his vocabulary by listening to American music. He first came to the United States to earn a graduate degree in Spanish literature at the University of Massachusetts.

"It is never easy to be away from your place of birth, your country," Candau says. "But I think that, compared to other times, the immigrant in the 21st century has it pretty good. Transportation is easier. With the Internet and communications technology, you can follow events and connect with your country much more easily than before."

The Challenge of Something New

Candau's first book, a study of the contemporary novelist José Mariá Merino, appeared in 1992. Since then, he has published many essays on 20th-century prose and poetry, as well as a second book that examines literary depictions of Spain's provincial towns. His work in progress explores how poets and novelists since the 19th century have portrayed the Spanish street.

Candau is especially interested in urban literature from the 1920s, when avant-garde writers dramatized the impossibility of representing the "impulses and stimuli" experienced by a walker in the city. He is also intrigued that in the 1950s, while Spain was still under the dictatorship of General Francisco Franco, many novels and poems included scenes in public spaces. In these works, Candau says, the action unfolds "under the watchful eye of the censor."

This is the first book Candau is writing in English. The challenge of trying something new appealed to him, and so did the possibility of making his work accessible to his colleagues outside the Spanish program. He admits, a little ruefully, that he wrestles with word choice more than he otherwise would, that he has revised certain paragraphs again and again. As he explains, "The normal obstacles are multiplied when you write in another language." Yet the published book will vindicate the advice he gives to his students: Don’t let the obstacles drive you from the path.

Antonio Candau

Photo: Daniel Milner