LENS Diagram

Understanding an Epidemic

Researchers Delve into the Expanding Opioid Crisis—and Work to Combat It

Architect Bill Ayars (MGT '01) knew his daughter, Jennifer, had struggled with substance abuse since high school. But he hoped she could conquer her demons. She earned a degree from culinary school, worked at a restaurant in Phoenix, then moved to Boulder, Colorado, to be closer to her younger sister.

"It seemed like things would improve," said Ayars, who lives in Bay Village, Ohio.

Jennifer returned to Ohio in the fall of 2015. Six months later, she was found dead from an overdose. She was 28. Doctors said she had traces of the powerful synthetic drug fentanyl in her system—a sure sign that she had fallen prey to the ongoing opioid epidemic.

Jennifer's story tragically illustrates some of what Case Western Reserve faculty know about this drug crisis.

Their research underscores how difficult it can be to overcome an addiction, how easy it can be to score a fix and why the latest generation of drugs is so deadly.

Prior to overdosing, Jennifer had tried to get clean, Ayars said. She was staying in a house with others who were recovering and seeing a therapist every week. Despite her best intentions, he added, she fell in with some old friends from her days as a drug user, and took something so powerful that it killed her.

"Relapse is the rule, not the exception to the rule," said Mark Singer, PhD (SAS '79; GRS '83, social welfare), the Leonard W. Mayo Professor in Family and Child Welfare and a member of the Northeast Ohio Heroin and Opioid Task Force. It takes "a good two years of sobriety" to see if a person can stay clean over the long term.

What's more, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and its chemical cousin carfentanil are so potent that even tiny amounts can be lethal, making accidental overdoses increasingly common. "The margin between getting as high as you want to be and dying is very slim," said Ted Parran, MD (MED '82), the Carter and Isabel Wong Professor of Medical Education, who directs several substance abuse treatment programs in Ohio.

While stanching the epidemic appears to be increasingly daunting, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a report this summer analyzing the issue and offering recommendations. The committee that issued the report included Lee Hoffer, PhD, a Case Western Reserve anthropologist who studies illicit drug markets, and Linda Burnes Bolton, DrPH, RN (HON '11), a member of the University's Board of Trustees who works at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles as the health system chief nursing executive, vice president for nursing, and director of nursing research.

The recommendations include expanding access to treatment and developing non-addictive alternatives to the opioid painkillers that helped spark the crisis in the first place.

Hoffer, who uses computer software to simulate communities of drug dealers and users, said that while dealers play an important role in opioid markets, many people with addictions often obtain their drugs with the assistance of fellow users. As a result, getting users into treatment should disrupt opioid drug markets as effectively as arresting dealers.

Treatment and harm-reduction strategies that include relapse prevention, addiction counseling, needle exchanges and opioid-replacement therapies such as methadone are key to dealing with the epidemic, as is the overdose-prevention drug naloxone.

Moreover, because some people with mental health issues may use drugs to self-medicate, drug-related treatment alone won't necessarily keep them clean, and they will need other services as well, Singer said.

Bill Ayars found that sorting through the various treatment options for his daughter was complicated and exasperating. So this year, he founded the Emerald Jenny Foundation (emeraldjennyfoundation.org) to provide families with a searchable online database of treatment providers throughout Ohio.

"If I can help people get to where the help is, then I'll have accomplished something," he said.

A GRIM REALITY

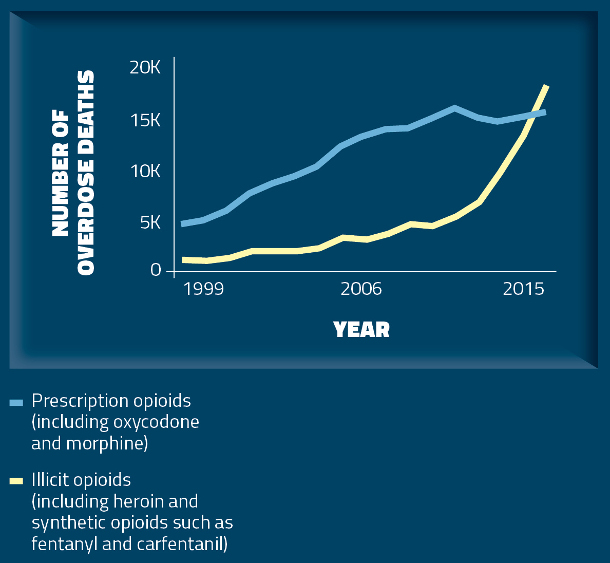

"Since 1999, the number of opioid overdoses in America have quadrupled according to the CDC. Not coincidentally, in that same period, the amount of prescription opioids in America have quadrupled as well. … We have an enormous problem that is often not beginning on street corners; it is starting in doctor's offices and hospitals in every state in our nation.

"… As access to prescription opioids tightens, consumers increasingly are turning to dangerous street opioids, heroin, fentanyl alone or combined, and mingled with cocaine or other drugs. …"

—Interim report by President Trump's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis

The most effective treatment involves a combination of:

- Sobriety-oriented counseling

- Involvement in a 12-step recovery community

- Monitoring and surveillance

- Medication-assisted treatment

- Addressing co-existing problems such as mental illness and sexual abuse

Facts:

- The typical opioid abuser is young, white, and rural or suburban

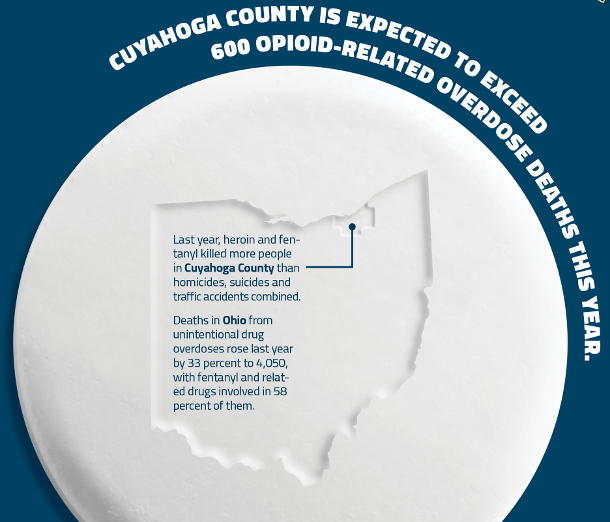

- The death rate nationally from most synthetic opioids increased 72.2% from 2014 to 2015. The states with the largest increases were Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Ohio, Rhode Island and West Virginia

- Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine

- Carfentanil can be 100 times more powerful than fentanyl

- 91 Americans die everyday from opioid-related overdoses

*SOURCES: CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION / CUYAHOGA COUNTY MEDICAL EXAMINER'S OFFICE / OHIO DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH / THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, ENGINEERING AND MEDICINE / MARK SINGER / TED PARRAN