feature

Cultivating Creativity

by Andrea Appleton

Richard Boyatzis

Richard Boyatzis

Tony Jack

Tony Jack

Stressful day? Some quiet contemplation is more likely to calm you down than smoking or knocking back another cup of coffee.

Such advice may sound like feel-good mumbo jumbo, but now we know it's backed up by hard science.

Advances in imaging research have allowed scientists to demonstrate that activities such as meditation engage a part of the body known as the parasympathetic nervous system, or PNS. The system slows the heart rate and helps the body recover from stress.

"Why do some people do breathing exercises or go for a walk outside when they take a break?" asks Richard Boyatzis, PhD, Distinguished University Professor, H.R. Horvitz Professor of Family Business and organizational behavior expert. "It's because in popular language it 'centers' them. That centering experience is very much at the heart of the parasympathetic nervous system."

Boyatzis has suspected for some time that an inspiring conversation might have the same effect. A few years ago, he teamed with Anthony Jack, PhD, an assistant professor of cognitive science, philosophy and psychology, to see if a particular kind of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would confirm his ideas. Specifically, he wanted to know if different parts of the brain would be activated based on the type of coaching to which people were subject.

It was a crash course in neuroscience for Boyatzis, who has won international acclaim for his work on coaching styles and emotional intelligence. But, he says, it was worth it.

"When you're a scientist, you're curious above all else," Boyatzis says. "And in this case, the curiosity is driven by not just the theory I've been working on, but the huge implications the theory has for helping people learn and build better lives."

A research team led by Jack and Boyatzis published its first study last year in Social Neuroscience. A follow-up study is underway. The two men are early in their research, but their initial findings have implications for how people are coached, taught and motivated across the range of human experiences.

Tracking Brain Activity

Psychologists have used functional MRI (fMRI) for decades to understand which areas of the brain are associated with particular mental tasks. These images measure brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow in different areas of the brain. The vascular system sends additional blood to areas of the brain that are in use, and researchers have used that function to illuminate everything from face recognition to the experience of grief. New research has linked particular regions in the brain with the parasympathetic nervous system. But the neuroscience of social interactions is still quite young, partly because it can be difficult to simulate real-world scenarios in experimental settings.

"Social interactions are amorphous; they go on their own path," Jack says. "And in an experiment, you want everything locked down and you want to control every element so that you can make good scientific inferences."

For the pair's first fMRI coaching study, college students met with interviewers who used one of two coaching styles—one focused on compassion, the other on compliance. The compassionate approach began with just one open-ended question: "If everything worked out ideally in your life, what would you be doing in 10 years?" The coaching-for-compliance approach used a series of focused questions about the student's academic experience. ("How are you doing with your courses? Are you doing all of the homework and readings?")

Boyatzis' prior research, conducted in collaboration with colleagues and PhD students, had shown the compassionate approach leads to more behavioral change than coaching for compliance. But whatever the interaction—parent and child, doctor and patient, manager and employee—the latter is much more common, he says. "Constructive criticism is still criticism in my theory," he says. "So when somebody says to you, 'You should put another sweater on your kid,' that's what I call [coaching for compliance]."

The new study's interviews aimed to help the students build a relationship with the interviewers so they would respond during the study more naturally. Researchers then scanned students' brains while students watched videos of mock coaching sessions based on the respective methods.

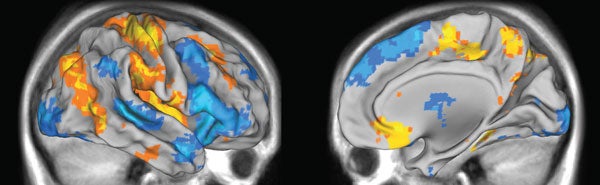

The results clearly showed that students' brains responded differently to the two coaching styles. The image—after pertinent data is extracted and averaged and then mapped on a 3-D generic human brain—is a cartoonish corrugated hemisphere painted in fluorescent yellows, oranges and blues. The blues indicate areas more engaged by coaching for compliance; these areas also are associated with focused attention and stress responses. The oranges and yellows show areas that responded more to compassionate coaching; some of these regions are involved in creative problem solving, taking a broader perspective, visioning and empathy.

The results of a similar, as yet unpublished, follow-up are even more compelling. In that project, repeated coaching-with-compassion sessions increased activity in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex, an area that helps create a sense of purpose in life. It also triggers the parasympathetic nervous system, relaxing the body and reducing stress. These fMRI results thus appear to support Boyatzis' theory that compassionate coaching engages the PNS. Research has shown that people are more creative and better at handling complex cognitive concepts when the PNS is activated. Evidence links a stronger parasympathetic response to good physical health as well.

Boyatzis also had speculated coaching for compliance would activate the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), and fMRI results appear to support this. The SNS activates the fight-or-flight response to stress, raising one's heart rate, pulling blood from the brain and increasing blood sugar. While this response is vital when a person is in physical danger, something as minor as a dropped cell phone call—or, as this research indicates, a misguided pep talk—can activate the SNS.

In short, brain scans appear to mirror what Boyatzis has long claimed: The most effective coaching is the compassionate kind. Moreover, the follow-up study indicates the effect is "dose dependent." Brain regions associated with the PNS were more engaged after repeated positive interviews than they were with a single session. When he saw the fMRI results from these studies, Boyatzis says, "It was pure elation."

While Jack and Boyatzis pursue this line of research, they and colleagues also have a long list of ongoing and future collaborations, including investigations into the neural patterns that make leaders effective when they're under stress and the ethical decision making of ground troops in extreme conditions.

"At this point, we have too many ideas," Jack says. "We say to one another, 'What would really be meaningful? OK, that means we should pick this thing from the list.'"

Coaching each other with compassion, it turns out, is helping these researchers figure out their own priorities.

To learn more:

- Visioning in the brain: An fMRI study of inspirational coaching and mentoring (pdf)

- Dehumanizing the enemy

- Coaching With Compassion: Inspiring Health, Well-Being, and Development in Organizations (pdf)

- About Richard Boyatzis, Distinguished University Professor

- About Assistant Professor Anthony Jack

Read More

Exploring the Brain

-

Cultivating Creativity

Brain scans show power of compassionate coaching.

-

Looking Within

New imaging techniques could spur better treatments.

-

Going Deep in the Brain

Locating best place to deliver electrical stimulation.

-

Restorative Touch

Giving man with prosthetic hand the ability to feel what's in his grasp.

-

Fearless

Alumna Lisa Beth Allen (WRC '83) shares what life is like after traumatic brain injury.

-

Cultivating Creativity

Brain scans show power of compassionate coaching.

-

Looking Within

New imaging techniques could spur better treatments.

-

Going Deep in the Brain

Locating best place to deliver electrical stimulation.

-

Restorative Touch

Giving man with prosthetic hand the ability to feel what's in his grasp.

-

Fearless

Alumna Lisa Beth Allen (WRC '83) shares what life is like after traumatic brain injury.