features

Data Guru

PHOTO: KEVIN KOPANSKI

PHOTO: KEVIN KOPANSKI

As Ohio's housing crisis crested a decade ago, its poorest communities felt the deepest pain. Foreclosure filings hit some 14,000 homes in Cuyahoga County in 2007 alone. Elected officials and social service providers were struggling to track and fight the epidemic when Case Western Reserve's Claudia J. Coulton quietly stepped up to help.

Her not-so-secret weapon: public data.

It's been said that Big Data is the new oil—a transformative force shaping this century the way oil did the last one. If so, Coulton is one prolific prospector.

A Distinguished University Professor at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Coulton, PhD (GRS '78, social welfare), has made it her mission to collect and analyze massive amounts of information, mining for patterns that humans could never recognize without the aid of computers—all to better inform policymakers and improve the lives of children, the poor and the suddenly vulnerable. Her approach has become a model for academics and nonprofits around the country.

When Cleveland became ground zero for the national foreclosure crisis, Coulton—the Lillian F. Harris Professor, and a founder and co-director of the Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development at the Mandel School—culled, developed and interpreted block-by-block statistics so locals could form a battle plan to combat blight and abandonment.

For close to four decades, Coulton and her colleagues have amassed on-the-ground data and analytical studies to better inform policymakers. But they have done even more.

In the early 1990s, they were pioneers in transforming how information was compiled and analyzed—effectively helping to create Big Data before the term was popularized. Today, the center's free, public online system is used by governments, organizations and interested citizens to turn kaleidoscopes of millions of disparate factoids into crystal-clear patterns.

Leading by example, Coulton has demonstrated how her profession can harness reams of information for the public good. "Data has changed the conversation," she said.

Consider just a few instances: When government officials in Cleveland sought federal dollars for a different approach to fight foreclosure-spawned blight, they successfully used her data to buttress their arguments. When a Coulton-led report showed city residents couldn't get to available jobs in outer-ring suburbs via public transportation, the transit authority adjusted its routes. And Coulton's innovative method (developed with center Co-Director Robert L. Fischer, PhD) of marrying public records with sensitive individual records—while still keeping identities private—led to new insights into how lead poisoning affects school readiness.

"In figuring out how to match community data and [anonymous] individual records to generate valuable insights without compromising privacy, Case Western Reserve University has been a leader," said Alaina Harkness, who, until recently, was a senior program officer at the MacArthur Foundation, which has supported Coulton's work. (Harkness now is a fellow with the Brookings Institution.) "Claudia is the model that we need: a translator who can bridge academics, practitioners and policymakers. She is a source of inspiration, grounded locally and globally influential."

PHOTO: KEVIN KOPANSKI

PHOTO: KEVIN KOPANSKIClaudia J. Coulton and Robert L. Fischer

Growing Up in the Great Society

Coulton traces her passion for social change to the inspiration of her mother, Laverne, and, before that, of Martin Luther King Jr.

"She didn't lead a march on Washington, but she was active in civil rights in Lyndhurst [a Cleveland suburb]," Coulton recalled. "She supported the Voting Rights Act and felt pushback in an all white neighborhood."

Her mother's example influenced Coulton and her brother, Rob, who recently retired as a Cleveland Clinic administrator. Their father, Robert, an engineer, passed on a love of mathematics to his daughter.

Aiming for a career in social work, Coulton received a bachelor's degree in sociology from Ohio Wesleyan University and soon began working for a state hospital—"the kind of bleak institution we don't have today," she said.

But Coulton grew dissatisfied with 1960s-era Great Society programs, which she felt did little to address root causes of persistent poverty. The frustration drove her back to academia to search for answers and better tools to affect public policy.

She earned her master's degree in social work from The Ohio State University and her PhD from Case Western Reserve. In 1978, she joined the Mandel School faculty.

A decade later, then Mandel School Dean Arthur J. Naparstek invited Coulton to contribute to a six-city, data-driven Rockefeller Foundation study examining persistent urban poverty. "Poverty had been my first and foremost concern, even before my professional career," she recalled. That project paved the way for the creation of what's now the Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development, which Coulton co-founded.

Steven Minter (SAS '63, HON '89) was then president of The Cleveland Foundation, which also supported the six-city project. In his view, Coulton's work on urban poverty was decisive. "Claudia had a lot of influence on how the whole Rockefeller Foundation program began to evolve nationally," said Minter, now an executive-in-residence at Cleveland State University. "From that early start, [her] work … influenced other cities in that network. You'd have to call her one of most important leaders we've had in the discipline."

From Paper to Punch Cards

Coulton attacked the analysis of Cleveland poverty with her usual vigor, asking for data "from every agency that would work with us." The project used maps and statistical analysis to discern patterns. The data sets included monthly enrollment in Aid to Families with Dependent Children, food stamps and Medicaid, as well as birth and death records, crime reports, school records, child maltreatment and neglect reports, and employment.

Coulton thought the public data contained in birth certificates—birth weight, mothers' prenatal care and marital status—could be a gold mine. She sensed that by feeding enormous amounts of data into a computer, she could understand children's health issues that began even before birth. But it was 1988, and the certificates were kept only in paper form.

"We went to the basement of Cleveland City Hall, copied all the records, then brought them to campus and keyed them into the university's mainframe computer," said Coulton. Other agencies gave them huge nine-track reels of tape. The resulting data system—with 36 million entries—showed a concentration of problems in specific neighborhoods that demanded greater coordination of services.

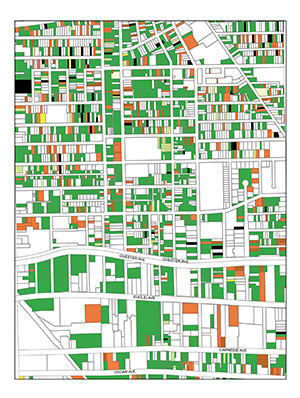

The center stripped out private information, then made other statistics from that system publicly available in 1992 when it debuted the Northeast Ohio Community and Neighborhood Data for Organizing (NEO CANDO). With support from local nonprofit organizations and partners, including the Gund and Cleveland foundations, the free system (neocando.case.edu) offered a public trove of millions of pieces of data from 17 counties. Questions about U.S. Census figures, crime statistics, property characteristics and mortgage lending data, public welfare and school attendance can be answered at regional levels, block by block and everywhere in between, creating a statistical portrait of an area. NEO CANDO now handles 23,000 queries a year.

"Claudia looks at the influence of where we live on how we live. No other researcher has provided the unifying focus on the power of neighborhood in individual and family well being," said Fischer, who, in addition to co-directing the poverty center with Coulton, is a research professor at the Mandel School.

Not only is Coulton's approach a national model, but her former students apply her know-how in other cities. The National Neighborhood Indicators Project, a 30-city consortium that queries integrated data to address community needs, also relies on her as an inspirational co-founder.

These days, Coulton's to-do list remains long and ambitious. On her current agenda: preparing for publication a MacArthur Foundation-funded study investigating how surrounding conditions affect young children's school readiness. Coulton and Fischer are leading the study and pairing, for the first time, data on environmental factors such as crime statistics, property foreclosures and vacancies with three years of school records for Cleveland kindergartners. Coulton also will lead a childhood asthma study, which, also for the first time, will link data from electronic medical records with information in the center's longitudinal data system on children.

Coulton still works 10-hour days to meet the demands of teaching, writing and traveling. And she continues to bring a dispassionate approach and high energy to her lifelong passion for social justice.

"I recently looked at what she'd done in the previous year—the high-impact work, the grants, publications and teaching," said Grover C. Gilmore, PhD, the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Dean in Applied Social Sciences and a professor of psychology and social work at the Mandel School. "I told her: 'You're the duck moving across the water, traveling a graceful path. Everyone says, what a beautiful peaceful scene. And underneath, the feet are paddling tremendously.'"

Coulton has no plans for retirement, and remains committed to serving poor communities.

"Poverty is higher now than in 1979 when I started to worry about all this," she said. "And now there's less [public] money to fight it, so we must be more strategic. This is still our job: to empower agencies, residents, volunteers and decision makers to do the very best with what we have."

Mining Data to Benefit the Community

Claudia Coulton and her colleagues at the Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development are working on projects involving:

Early childhood education

Beginning in 1999, the center documented the quality of many local early learning programs at the request of what's now Cuyahoga County's Invest in Children—a public/private partnership focused on young children. The partnership subsequently encouraged providers to adopt voluntary state standards for high-quality preschools and, in 2007, launched a Universal Pre-Kindergarten Program. But did the higher-quality programs give children a better start? The data said yes: Students in high-quality programs scored higher for kindergarten readiness, which translated into significantly better odds for passing the third-grade reading proficiency exam.

Lead hazards

The center has combined state blood test results with data on neighborhood housing conditions in Cleveland and is working with the Invest in Children partnership to examine the relationship between kindergarten readiness and elevated lead levels. The center found that 22 percent of children in the Universal Pre-Kindergarten Program had lead levels above the public health standard for concern—and those children, in turn, showed much less progress in skills related to school readiness than other children in the program. The partnership is working to develop strategies to better meet the needs of these children.

Keeping families intact

Cuyahoga County launched Partners for Family Success last year, a program to help homeless families that could not have moved forward without the center's human services data. Among other things, the data was used to help develop a list of families eligible for the program. The program offers housing and mental health services to homeless parents to help them achieve stability so their children can be returned to them from foster care. Coulton also provided advice on the design of the program, which is receiving national attention.

Repairing neighborhood devastation

The foreclosure crisis slammed Cleveland and surrounding communities. In 2012, then-Cuyahoga County Treasurer Jim Rokakis, JD, knew more funds were needed to slow the blight's spread. He appealed to the U.S. Department of Treasury: "We said, 'We can prove to you that demolitions can prevent more foreclosures.'" In June 2013, Rokakis said, the federal government made funds available to hard-hit states, not just to help homeowners avoid foreclosures but also to demolish houses. "The data from [the center's community data system] was absolutely essential," said Rokakis, now director of the Thriving Communities Institute at the Western Reserve Land Conservancy.

Coulton's Former Students Gather Data from Around the World

Gautam Yadama, PhD (SAS '85, GRS '90, social welfare), and Shanta Pandey, PhD (GRS '89, social welfare), now professors at Washington University's George Warren Brown School of Social Work, met as graduate students in one of Professor Claudia Coulton's statistics classes at the Mandel School. Coulton's work not only brought them together—the pair married in 1990—but also inspired them to analyze problems in developing nations.

"Claudia was influential in helping me think of ways to use existing data that others have collected," said Pandey, whose students are analyzing national household survey data from more than 90 developing countries to study global trends such as child marriage, intimate partner violence and fertility patterns in those countries.

Yadama, who also serves as his university's assistant vice chancellor for international affairs for India, is using another Coulton strategy: combining data—in this case on environmental changes in rural India collected by satellite, community organizations, social media and even smartphones—to find patterns otherwise not apparent. "It helps capture the reality of rural poor households and the way livelihoods are impacted by environmental risks such as frequent droughts."