FEATURE Performing Arts

She's a Mover

Gina Gibney's Dance Steps Reverberate Far Beyond Her New York Studios

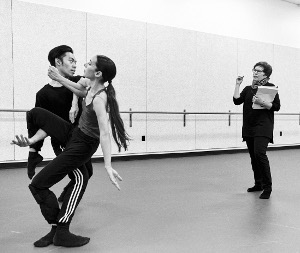

PHOTO: Roger Mastroanni

PHOTO: Roger MastroanniGina Gibney rehearsing her Drafting Foresight, a world premiere for GroundWorks DanceTheater in Cleveland, with dancers Michael Marquez and Felise Bagley. The piece was part of the company's 2017 spring concert series.

The economic crash of 2008 wreaked havoc on millions of Americans—including choreographer and dance impresario Gina Gibney.

Everything Gibney had built since 1991 seemed in peril: her namesake dance company in New York City, the studio spaces she had opened to other artists to showcase their work, the dance classes, and the programs she launched to help at-risk youth and victims of domestic violence heal through movement.

“We almost closed the doors,” said Gibney, MFA (WRC ’79, GRS ’82, theater). “For a time, it seemed there was nothing coming in. It was a really scary period. But I said, ‘I don’t want to lose the space.’ It was a platform that supported so many artists.”

So she hunkered down. Absorbing every aspect of Gibney Dance, she became the bookkeeper, accountant and finance director. She learned to read spreadsheets. She scrimped and saved. And counterintuitively, as other cash-strapped tenants in her building at 890 Broadway near Union Square vacated, she moved into their abandoned rooms.

The risk paid off. “We just had this horrible year,” she later told the New York Observer, “but one thing led to another and the next thing you know we’re doing it.”

By 2011, two decades after she had begun with one studio and an office, Gibney was operating eight studios and related spaces to the tune of 15,000 square feet. Soon, she was renting much of it for rehearsals of such Broadway shows as Nice Work If You Can Get It, Cinderella and Lucky Guy, starring Tom Hanks.

Since then, Gibney’s reputation only has grown.

In 2013, when the financially troubled Dance New Amsterdam declared bankruptcy and cleared out of its 36,000-square-foot space opposite City Hall Park, the city (which owns the building) approached Gibney to take up residence.

“We wanted to preserve it for the dance community,” Deputy Commissioner of Cultural Affairs Margaret Morton told The Wall Street Journal at the time. Gibney accepted the offer and, in 2014, signed a 20- year lease for the building, which is at 280 Broadway.

That same year, the New York Observer dubbed her a “power broker” and “one of contemporary dance’s most powerful figures in New York.”

And in June, Gibney will receive the Ernie Award from Dance/USA—the national service organization for professional dance—for extraordinary leadership and working behind the scenes to empower artists and support their creativity.

Lucinda Lavelli, MFA (GRS ’77, theater; MNO ’91), dean of the University of Florida, College of the Arts and a friend from their Case Western Reserve University days, said: “I can’t imagine any other dancer who has done what she has done. There are many choreographers who travel to New York and leave the profession; they go into banking or education or even massage therapy. But every move Gina has made has been about dance.”

All the accolades embarrass Gibney Dance’s soft-spoken founder, artistic director and CEO. “I’ve been working at this a very long time and there are very many unsung heroes,” she said. “I’d rather not be positioned as a power broker. I never anticipated that this would happen.”

On any given day, Gibney Dance offers workshops in everything from contemporary forms to movement research. The company is flourishing, and other choreographers rely on Gibney’s spaces in a tight Manhattan real estate market.

One winter afternoon, Gibney made her usual rounds, peering in on classes and rehearsals through the glass fronts of the dance spaces, chatting up arriving and departing students and performers. She sat for the first 10 minutes of a demonstration of her latest dance piece, Folding In, and took particular note of the booking schedules outside each studio. “If I see a gap,” she said, “I ask about it.”

During her walk through, she spotted and removed a couple of errant scraps of wood and duct tape, likely detritus from ongoing construction: 280 Broadway remains a work in progress and, ultimately, is expected to include an additional half-dozen pre-production labs and rehearsal halls.

Amid this activity, Gibney herself has not performed for some time. “My physicality these days is more about swimming, gardening and stretching.” Lest there be any mistaking the point, she added, “I’m a mover.”

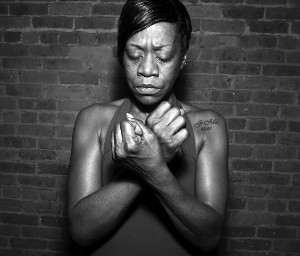

PHOTO: Julieta Cervantes / Gibney Dance

PHOTO: Julieta Cervantes / Gibney DanceSandra was a participant in the Gibney Dance workshops for survivors of domestic violence. Not a professional dancer, she created "Here to Tell," a piece about her journey to find strength. "It was very moving, ... and had minimal movement and text, but maximum emotion," said Gina Gibney.

FINDING HER VOICE

Gibney grew up in a family of “capable and determined” adults in Ontario—not the Canadian province, but a farm town with a small industrial base about 90 minutes southwest of Cleveland.

Her maternal grandmother, an interior designer in Columbus, kept a massive table in her basement, where she’d cut and sew upholstery fabrics or gather an army of women to create what Gibney called “an assembly line of generosity” to make hundreds of Easter baskets or charity Thanksgiving dinners. “It would always be about helping the poor and the needy and the children,” Gibney said.

Her parents each had been married before, and Gina, born when her mother was 44 and her father was 52, came of age with three half-brothers and a full sister. Ken and Jane Gibney were entrepreneurial, artistic and natural mentors—qualities Gibney likewise embodies. “I have no problem being a reflection of my parents,” she said. “They were amazing people.”

Her father supervised and trained insurance agents for a company he later bought. He was musical and charming, and drew whimsical cartoons for his young daughter before leaving on business trips.

Her mother was a skilled homemaker active in the community, who presided over a local theater company and offered wise counsel to the mothers of Gina’s friends who flocked to her for advice. Years later, she joined her husband’s company—and, Gibney recalled, sharply increased sales.

When Gibney was around 4, she began taking traditional tap and ballet classes at the Ethyl Battin Dance Academy, named for the former Rockette. But growing up, Gibney found herself more committed to student government and social justice. “I drifted from dance because it didn’t seem serious enough for me,” Gibney recalled.

That attitude extended to her early years at Case Western Reserve, which she chose in part because it was close—but not too close—to home, and, with its broad strengths in the liberal arts, allowed Gibney to keep her options open.

She set out on a vaguely pre-law route and flirted with psychology, history and urban studies. But, in her second year, she began moving back to dance.

“I missed being physical,” Gibney said. “So I took some dance classes and it truly felt like starting over. It tapped into every part of me. It took me a while to have the courage to announce this as a profession. But I felt it had much more meaning than anything else I was doing.”

And when she did make her choice, Kathryn Karipides (GRS ’59, physical education) and Kelly Holt—then co-directors of the university’s MFA dance program—were there as a “watchful team,” providing Gibney with essential space to explore her creativity and crucial support when she hit a wall.

Karipides, who also founded the university’s dance department and now is the Samuel B. & Virginia C. Knight Professor Emerita of Humanities, remains a close friend of Gibney’s and serves on the honorary board of Gibney Dance.

The two talk frequently.

Karipides vividly remembers Gibney’s ambitious student production of “Chair People,” a “powerhouse” piece with a cast of about 20 dancers, each with a folding chair. “Gina has always had a clarity of intention,” Karipides said. “No matter what she is working on, she intelligently thinks things through and then delivers as dependably as a Mack truck.”

After earning her MFA, also at Case Western Reserve, Gibney proceeded to Seattle, connecting professionally with Gail Heilbron Steinitz, MFA (WRC ’73; GRS ’75, ’76, theater) and Mark Morris, founder of the Mark Morris Dance Group in New York City.

“Mark was all about breaking rules and telling people to take risks,” Gibney recalled. “He’d say, ‘What do you mean you’re afraid to use that music?’ Mark gave me the opportunity to move outside the boundaries of my strict, classical modern dance training. But if I hadn’t had the basics, I couldn’t have broken out and found my own voice.”

Gibney also broke through personally: She was gay and, in the bustling, open Seattle metropolis, was able to come out. “It was,” she said, “a moment of permission.” Last year, Out magazine named Gibney to its annual list of the 100 most influential LGBTQ people.

PHOTO: The Kathryn Karipides Papers, Kelvin Smith Library at Case Western Reserve University

PHOTO: The Kathryn Karipides Papers, Kelvin Smith Library at Case Western Reserve UniversityAs a student, Gina Gibney danced in this campus production of "Four by Four," choreographed by CWRU's Kathryn Karipides.

CREATION FOLLOWED BY HEARTBREAK AND REGROUPING

In the late 1980s, Gibney moved to New York City and worked as an independent—albeit struggling—choreographer. It was Pamela van Zandt, now Gibney’s life partner of 27 years, who urged her to make the bold move of launching her own company in a city already teeming with dance.

“Pam is the singular business mentor, coach and champion who has been behind me every step of the way,” Gibney said. She “wanted me to have an artistic home.”

A human resources and operations pro who has worked for decades as an executive—first at Condé Nast Publications and later Estée Lauder Cos. Inc.—van Zandt “called in favors from all corners to get [the first studio] up and running,” Gibney said. She also helped incorporate the company, develop a regular group of dancers, and build the board—and then became the founding chair. “She made it happen,” Gibney said.

But almost as soon as the dance company formed in 1991, Gibney’s father died—and then her mother three years later. In early 1995, exhausted, she “very abruptly” disbanded her company and left dance entirely for a year and a half. Her two big accomplishments during this period were raising a Shetland sheepdog named Andy and growing a garden, digging and processing what she had experienced.

Gibney regrouped sufficiently to launch her enterprise anew in 1998 as an all-female troupe, believing that was the best way to showcase “the power, passion and equality of women.” The company remained single-sex for a decade, a prolific time during which Gibney created six full-length works. In 2008, Gibney Dance went coed again to expand the choreographic options. “I’m happy that we’re more balanced now,” she said. “It’s more representative of the world we live in.”

PHOTO: Gus Chan / The Plain Dealer / Advance Media

PHOTO: Gus Chan / The Plain Dealer / Advance MediaGibney led a master class on campus in 1996 for non-dance majors.

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

Today, Gibney’s commitment to the world around her informs what may be her most intensely felt undertaking. In 2000—during the time the dance company was all-female—Gibney Dance launched its Community Action initiative to help survivors of domestic violence express what they have endured through movement.

Gibney initially had resisted the idea of working with victims.

“I was worried that the gravity of the situation— the trauma that women had experienced—would put too great a weight on our organization,” she said. But she eventually changed her mind, pained by “the idea that you could not be safe in your own body, or in your own home.”

Community Action since has helped survivors in a dozen states, including Ohio, as well as in seven other countries, including Sweden, Turkey and Rwanda. It also has trained dancers and social-action organizations to create their own programs.

One of many beneficiaries is Sandra, a 56-year-old information-technology technician who said she was in an abusive relationship for a number of years. She believes Gibney is one of the “angels” who came into her life through divine intervention in 2007. Slowly, Sandra began to express her pain through hand gestures and small motions. Within two years, she had created a 10-minute solo piece, Here to Tell, which she continues to perform at arts and social justice events.

“It is a fuller expression of what I was feeling,” she said. “…I feel free now.”

Gibney is gratified and inspired by what dance can do to lift both performers and audiences to unexpected heights. But perhaps what moves her most today is seeing a person in pain take flight in a place that has no mirrored walls or polished hardwood floors. It is when Gibney’s love of dance and her passion for community action merge and bring both dancer and choreographer to a state of elation.

“Some of the most powerful performances I’ve ever seen were not in New York City theaters, but in the most unlikely spaces—the basements of shelters, laundry rooms, conference rooms,” she reflected. “Performance is a suspension of belief, and when survivors witness art unfolding in such mundane spaces, they may begin to believe that anything—including change—is possible. Everyday life can be extraordinary and magical.”

Movement and Mood

Gina Gibney Draws Inspiration from Her Dancers

PHOTO: Mark Horning / GroundWorks DanceTheater

PHOTO: Mark Horning / GroundWorks DanceTheaterA performance of Gina Gibney's Drafting Foresight, a work that explores pivotal conversations and the memories that result. Dancers are: Michael Marquez (left) and Felise Bagley (right).

When Cleveland’s GroundWorks DanceTheater wanted a new piece for its 2017 spring concert series, it turned to a reliable creative force: Gina Gibney.

“It’s always a great experience working with her,” said David Shimotakahara, GroundWorks’ executive artistic director, who values the way Gibney brings dancers into the creative process and “collaborates with their ideas in a way that reveals something unique in each of them.”

Drafting Foresight (with music by Ezekiel Honig) was the fourth original work that Gibney—a Case Western Reserve alumna and founder, artistic director and CEO of Gibney Dance in New York City—has created for GroundWorks.

On a wintry afternoon midway through the rehearsal process, Gibney sat on a chair in the center of a downtown studio, keenly observing the swirl of movement, quietly jotting down thoughts, and encouraging the dancers to explore their own ideas and take risks as they molded the piece together.

The work involved four dancers in duets—a favorite Gibney form.

“I wanted to create duets that felt like conversations between people, that had a sense [not of] two people dancing for an audience, but two people actually conversing with each other,” Gibney said. “I’m not about shapes and patterns and the presentational aspects of dance. I’m really interested in the ability of movement to tell a story, express emotions and create a mood.”