|

To understand the film of any country, one must look at the context in which films were produced. The motion picture can be used in many ways by different people or groups with a message to get across. Films can be government propoganda, entertainment, or art, but no matter which category a film is placed, one thing is certain of all films made: films, because they cost money to produce, are all made within a structure of politics and economics and ,therefore, carry a definite message. This site gives a brief description of 5 distinct periods of the German cinema with some represenative films from each period. My aim is to put present these films as texts which can be read only by considering the contexts to which they belong. I have divided the study into 5 sections; The Formative years, Films of the Weimar Republic, Third Reich Propoganda Films, Post WWII Films, and The New German Cinema. Each period is defined by its own unique political agendas and methods of utilizing the power of the motion picture. Each section contains a brief summary of the period with some represenative films. The Formative YearsEarly experiments by Eadweard Muybridge, John D. Isaacs, and Ottomar Anschütz, although headed in the wrong direction, sparked an early interest in the potential of film in Germany. Max and Emil Skladanowsky are notable in that they invented the Bioscope (a double projector system) and presented their pictures publicly at the Berlin Wintergarten on November 1, 1895, predating the first public performance by the Lumières by over a month (their previous showings were all to private audiences). Oskar Meester was one of the most important German film pioneers. After

studying the work of Anschütz, the Lumeères, and Thomas Edison, Meester created

a projection system which substituted the Maltese Cross for the claw movement

of the Lumières. Meester's first film catalogue published in 1897 featured an

article which he wrote demonstrating his understanding of the potential of

film. "By its means historical events can henceforth be preserved just as they happened and brought to view again not only now, but also for the benefit of future generations." Among the films offered in Meester's catalogue were examples of the first close-ups, the first animation effects, and the first speeded-up motion effect. Early films were shown in Kintopps which were usually converted storefronts with white canvas on one wall. The Kintopps soon gave way to the Lichtspieltheatre, a structure especially designed for the exhibition of motion pictures. The German Kaiser was much interested in motion pictures. On his yaught, the Kaiser had a court photograher shoot films during the day which would be developed on board and shown later that day. This was an early indication that a German head of state had realized the potential of film as a tool to publicize and propogandize. Demand for films was so great that German companies began to import films from England, Italy, America, France, and Denmark, with the latter two supplying the most. The first German film to be seriously regarded by the press was Der Andere (The Other One), directed by Max Mack in 1913. And since the film was based on a play by Paul Lindau, it has the distinction of being the first Autorenfilm, or famous author films. "People began discussing the cinema as an art in 1913. In Germany such discussion arose in connection with the films of Paul Wegener" wrote Ceram in his book Archeology of the Cinema. One of the earlist examples of Wegener's art is Der Student von Prag (The Student From Prague) While some intellectuals scorned the new medium, others recognized its educational potential. The Organization for Cinematographic Study was founded in 1913 to encourage films of an instructive and scientific value, hoping to raise the standards of ordinary films. The organization proposed to underwrite the cost of production in instances where producers felt such films would not make a profit. One early example of the Lehrfilm (instructional film) occurred in a Berlin symphony hall in 1914. While a live orchestra played the overture to Bizet's Carmen, the audience watched a film of a conductor leading the musicians as if he were actually before them. This early experiment was an indication of the part the Lehrfilm would play in the following years. World War I encouraged the development of the Lehrfilm for the instruction and training of troops. Offshoots of the Lehrfilm included the Werkfilm (industrial film), designed for training employees, the Statistische Film which presented statistical data in animated graphs and charts, and the Wissenschaftlichen (scientific film), which described new apparatus or depicted the performance of a surgical operation. To many, the Lehrfilm held the promise of revolutionizing the dissemination of knowledge. The Golden Age of German FilmWWI brought a new agenda for the German film industry. With the entry of the

U.S. into the war in 1917, Erich von Ludendorff, Quartermaster General of the

Army, concluded that more drastic measures should be taken to meet the general

wave of anti-Germany propoganda coming from the well-equiped studio of its new

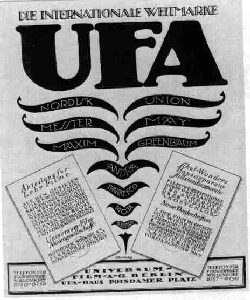

enemy. On December 18, 1917, the German High Command formed UFA (Universum Film

A.G.), which brought together prominent financiers and industrialists with the

largest film companies in Germany. The intent of UFA was soon realized by Ernst Lubitsch with his production of Madame Dubarryreleased in 1918. The film achieved a near revolution in the art of film. Lubitsch did with the camera what no previous German director had. Upon its release in the U.S. in 1920, Madame Dubarry, retitled Passion, was acclaimed the most important European picture since the Italian production of Cabiria. With Madame Dubarry, Lubitsch emerged as a director of would stature and the German film achieved its first breakthrough in the international market since the Armistice. In 1921, the Reich government divested itself of its UFA holdings, with the Deutsche Bank acquiring its shares. Reconstituted as a private company, the primary objective of UFA was to be the production of commercial films of high artistic value that would be capable of competing on the world market, especially the American. Germany was in poor shape by the end of WWI. Many citizens were dying of starvation as the country was faced with high inflation and widespread unemployment. The anguish of the period was reflected in Fritz Lang's two-part film, Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (Dr. Mabuse the Gambler), released in 1922. The film depicts an unscrupulous criminal who gambles with lives and fortunes. The Aufklärungsfilme "films about the facts of life" emerged during this period. Most of these films were actually sex films, only thinly veiled as education. Popular demonstrations and legal action against the Aufklärungsfilme occured throughout Germany. The National Assembly proposed the nationalization of the film industry which was rejected in favor of a National Censorship Law, adopted in May, 1920. Under this law children under twelve were prohibited from seeing films while children between twelve and eighteen could only be admitted to films which had been designated with a special certificate. No film could be prohibited due to its content. The most enduring of the films of the 1920's are those that came out of the

expressionist movement. As an artistic movement, German expressionism antedated

WWI. Film, the newest of the arts, was also the last to reflect expressionism.

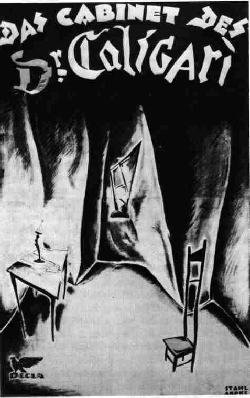

Two definitive expressionist films are Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), directed by Dr. Robert Weine in 1919-20,

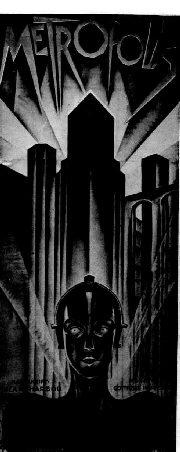

and Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926-27.

The pure expressionism of Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari and Metropolis, although among the most famous of German films from the 20s, was not characteristic of the several thousand motion pictures produced between 1919 and the end of the silent era. Although both were artistic and remain the quintessential examples of cinematic expressionism, neither Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari nor Metropolis were commercial successes. And while the German film achieved an international renown for the artistry of selected motion pictures, the industry never rested on a firm financial basis. This struggle between artistic expression and financial succuss would plague the German cinema for years to come. For some German filmmakers, success was measured by American popularity. Ernst Lubitsch was the first of the major German directors to accept an American assignment. He was asked by Mary Pickford (a popular American actress of the 20s) to direct Rosita. Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau's Der letze Mann earned him an invitation to direct American films. Murnau's American work consists of only four films: Sunrise (1927), The Four Devils (1928), City Girl (1930), andTabu (1931). After completion of Tabu, Murnau died in an automobile accident near Santa Barbara, California. Besides Lubitsch and Murnau, many other German directors and actors entered the American industy during the 20s, a trend that continues today. Fritz Lang, director of Der müde Tod, Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler and Die Nibelungen, was the principle German director to remain outside the American industry during this first wave of immigration. Lang had no desire to move to Hollywood. While visiting America, Lang told an interviewer that while he admired the technical resources of the American industry, he found American directors too commercial and less devoted to art than their German counterparts. Lang clearly had a different idea regarding the potential of film than did the American directors of the time. Third Reich FilmsNo period of German history is as infamous as that of the Third Reich. Hitler's rise to power on January 30, 1933, would have a profound effect on the course of the German Film. Dr. Joseph Goebbels was named Reichminister für Volksaufklärung und Propoganda (Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propoganda) by Hitler in March of 1933. This was the beginning of the most famous propoganda machine ever. To centralize his authority, Goebbels established the Reichskulturammer (State Chambers of Culture) for art, music, theater, authorship, press, radio, and film. The Filmkammer was established as an official section of the Kulturkammer. Goebbels was very interested in the potential of film as a propogandistic tool and took an active role in its development during the twelve years of the Third Reich. Goebbels summoned Fritz Lang to his office to offer Lang a position within the "new" German film industry. Just as Lang was not interested in making films in America, he accordingly had no desire in directing National Socialist pictures. Lang reminded Goebbles of his Jewish ancestry to which Goebbles replied that this would be overlooked. Lang could never bring himself to be at the mercy of the new order, so shortly after the interview, he left Germany for France where he began a new career, first in Paris and later in Hollywood. Lang's emmigration was followed by many German film notables: producers, directors, cameramen, technicians, writers and actors. These people, who had contributed so much to the German cinema during the fifteen-year life span of the Weimar Republic and made the German film an international success, left the country and took with them the "Golden Age" of the German cinema. The flood of talent leaving the country had a large impact on the development of the German film.

A Reich Film Law was enacted on February 16, 1934, which established a Censorship Committee. Under this law, a Reichsfilmdramaturg (Reich Film Supervisor) was designated to examine scripts and was given full authority to accept or reject those scripts. After a screenplay passed the Reichsfilmdramaturg, the completed film was shown to the Censorship Committee consisting of permanent members and four judges nominated by the Propoganda Mininster. This body was empowered to withhold permits for films if they were "likely to endanger the vital interests of the state or public order or safety, to offend National Socialist, religious, moral and artistic feelings, to have a corrupting influence, or to prejudice German prestige or German relations with foreign countries". Foreign films were also included under this law. Post World War II FilmsThe nucleus of Germany's pre-war film industry fell within the Soviet occupation zone. Soviet authorities quickly reopened, and by May 1945, thirty-six Lichtspielhäuser were functioning in the Soviet zone of Berlin. The British and American zones were comparitivley slow at getting the film industry going again. While the Soviet zone played older, non-propogandistic films, the allied zone adhered stictly to a policy of de-Nazification, making extensive use of German motion pictures not associated with National Socialist propoganda. In the name of democracy, both British and American authorities forbade combines and seperated the functions of production, distribution, and exhibition. This fragmentation of the German film industry actually served to prevent the development of a serious competitor. German citizens were shown Welt im Film (World on Film), the official Anglo-American newsreel, in an attempted goal of "educating German public opinion on sound democratic lines." Film policy in the American zone was guided by the Office of War Information Overseas Motion Picture Bureau (OWI). During the spring of 1945, German films were confiscated by the OWI in hopes of impressing upon the German people their responsibility for the war. Short documentaries of concentration camps were shown to German audiences during the first weeks of occupation. The OWI regarded film as a tool for the reeducation of the Germans. These films lacked entertainment value and were considered boring by most Germans. Germans were, however, curious to see certain American films such as Gone With the Wind, which had been censored during the Nazi era. But the film was not allowed in Germany as it did not meet the objective of reeducation.

Whether or not the OWI had succeeded in reeducating the Germans, it had succeeded in subordinating the German industry to the U.S., giving the American film a predominance in Germany which it exercises to this day. By 1948-49, about 70% of the pictures exhibited in the American sector were of Hollywood origin. The decade of the 1950's proved to be a time of crisis and transition for the West German film industry. The industry was in dire financial trouble, having lost its international market as well as a large share of its domestic market. German banks refused to make loans to German production companies, so many were forced to depend on private sponsors who were more concerned with making a profit than the artistic value of films. German producers and directors were reluctant to experiment with new techniques or themes. The German film appeared to have reached an artistic dead end. The 60s proved to be the darkest decade in the history of the postwar commercial German cinema. In 1959 West Germany produced about 106 films, 98 in 1960, and 75 in 1961. Many production companies closed while survivors struggled to maintain their share of the market, now seriously eroded by American competition and the growth of television. The times were epitomized by the return of Fritz Lang who had retired from the American film scence and chose to reenter the German scene after an absence of more than a quarter of a century. He returned in 1958 to direct a new version of Das indische Grabmal. Lang appears to have believed that the screenplay would be as valid in 1958 as it had been in 1920. Unfortunately, that was not the case as his movie was not received well. The German film seems to have bottomed out with the German western. Der Schatz im Silbersee (The Treasure of Silver Lake) and Flusspriaten des Mississippi (Mississippi Pirates) are two examples of films lacking in originality. As one critic observed, "They look authentic enough; the mountains, streams, plains and even the Red Indians are very familiar; but what is lacking is imagination and style. Often the impression is that directors have sat through many American films and then set out to copy them." It seemed as though the German cinema had entered a downward spiral from which it could not escape. |

UFA's raison d' être was clearly propogandistic. As noted by one film historian, "The

official mission of UFA was to advertise Germany according to German

directives. These asked not only for direct screen propoganda, but also for

films characteristic of German culture and films serving the purpose of

national education".

UFA's raison d' être was clearly propogandistic. As noted by one film historian, "The

official mission of UFA was to advertise Germany according to German

directives. These asked not only for direct screen propoganda, but also for

films characteristic of German culture and films serving the purpose of

national education".  . Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari,

based on a story by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, suggests the darker aspect of

expressionism with its probing of insanity. The authors originally intended for

the film to serve as an allegory against insane authority as represented by the

tyranny of Dr. Caligari, but the film ends with the harmless doctor telling his

piers that he can cure his patient now that he understands the root of his own

psychosis.

. Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari,

based on a story by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, suggests the darker aspect of

expressionism with its probing of insanity. The authors originally intended for

the film to serve as an allegory against insane authority as represented by the

tyranny of Dr. Caligari, but the film ends with the harmless doctor telling his

piers that he can cure his patient now that he understands the root of his own

psychosis.  Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926, emphasizes the importance of the spiritual as opposed to the material and

the notion that through choas and destruction a new and better world will come

about. The overthrow of the old order was an essential prerequisite for the

coming of the "New Man" and the establishment of the "Kingdom of Love". The final title reads: "There can be no understanding between

the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator."

Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926, emphasizes the importance of the spiritual as opposed to the material and

the notion that through choas and destruction a new and better world will come

about. The overthrow of the old order was an essential prerequisite for the

coming of the "New Man" and the establishment of the "Kingdom of Love". The final title reads: "There can be no understanding between

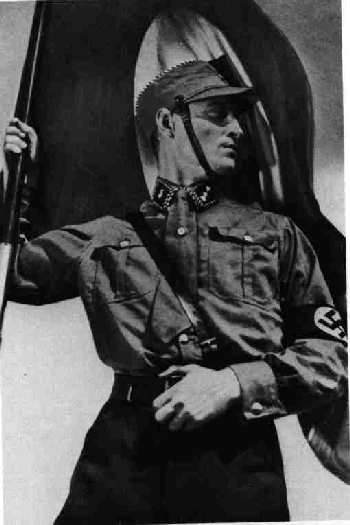

the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator."  Goebbels sought to assure the film industry that

its uncertainty was unwarranted. He then set about encouraging producers to

make films that were within the moral and political parameters set by the

regime. Arnold Raether, of the Ministry of Fine Arts, prefering a more direct

appoach, told producers that their purpose was to educate the people and to

propogandize. A string of nationalistic films such as Hans Westmar, directed by

DR. Franz Wenzler, were soon produced. These films were too political and

were not at all popular with the German people. Audiences were receptive to

entertainment but despised being preached to. Goebbles realized that propaganda

would have to be delivered in the form of entertainment. The historical film

was most suited to this purpose. Das Mädchen Johanna (Joan the Girl),

directed by Ucicky, which was shown at the International Film Congress in

Berlin 1935, presented Joan of Arc as a Hitler prototype. She was shown as a

leader who saved her people from despair and, like Hitler, was driven by her

belief in her country. The movie was well recieved by the German people.

Goebbels sought to assure the film industry that

its uncertainty was unwarranted. He then set about encouraging producers to

make films that were within the moral and political parameters set by the

regime. Arnold Raether, of the Ministry of Fine Arts, prefering a more direct

appoach, told producers that their purpose was to educate the people and to

propogandize. A string of nationalistic films such as Hans Westmar, directed by

DR. Franz Wenzler, were soon produced. These films were too political and

were not at all popular with the German people. Audiences were receptive to

entertainment but despised being preached to. Goebbles realized that propaganda

would have to be delivered in the form of entertainment. The historical film

was most suited to this purpose. Das Mädchen Johanna (Joan the Girl),

directed by Ucicky, which was shown at the International Film Congress in

Berlin 1935, presented Joan of Arc as a Hitler prototype. She was shown as a

leader who saved her people from despair and, like Hitler, was driven by her

belief in her country. The movie was well recieved by the German people.  The first post-war German production to recieve an

American license was Und über uns der Himmel (The Sky Above Us) directed

by Josef von Baky. This film portrayed Berlin as it was, with shots of the

miles of rubble and the hardships of its citizens. The more destroyed Germany appeared in a film, the more support it received from OWI.

The first post-war German production to recieve an

American license was Und über uns der Himmel (The Sky Above Us) directed

by Josef von Baky. This film portrayed Berlin as it was, with shots of the

miles of rubble and the hardships of its citizens. The more destroyed Germany appeared in a film, the more support it received from OWI.