launch

ISRAELI CAVE DIG

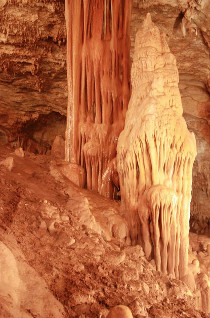

photo: Anne Dubitzky

photo: Anne DubitzkyDuring a trip this past summer, graduate student Yvonne McDermott scraped the floor of Manot Cave for artifacts and fossils.

In an enormous cave on the earliest land route for humans between Africa and Europe, graduate student Yvonne McDermott unearthed charred and shattered deer bones this summer—signs that humans or Neanderthals cooked in the cave.

"It's not unusual to find fossils and tools every day," said McDermott, who studies biology at Case Western Reserve, and has been a volunteer for two expeditions at Manot Cave in Western Galilee, Israel. "We're always hoping to find more pieces to the puzzle of our early history."

From an earlier dig, they already helped identify one critical piece: a 55,000-year-old partial human skull, suggesting human interbreeding with Neanderthals, who lived throughout Europe 350,000 to 40,000 years ago.

"We now think interbreeding between these species first happened inland just east of the Mediterranean Sea instead of mainland Europe—and nearly 15,000 years earlier," said Bruce Latimer, PhD (GRS '78, anthropology), visiting orthodontics professor in the Case Western Reserve School of Dental Medicine and co-director of the Manot Cave Project. The seven-story cave had been sealed by an earthquake for 30,000 years before being uncovered during sewer construction in 2008.

Since the cave's opening, Case Western Reserve has co-led six excavations with other universities and the Israeli government, bringing along a cross-disciplinary mix of students to dig, explore and study cave fossils for clues into the complex story of human evolution.

"We take it one bucketful at a time," McDermott said.