lens

Mapping Disease Risk

A novel approach to seeing connections between physical environments and the health of residents

Sanjay Rajagopalan

Researchers have long sought to understand how environments affect human health by studying factors such as water, air quality, tree cover, pavement and road density—in often laborious, manual, in-person studies.

But that's "the old-fashioned way," said Sanjay Rajagopalan, MD, a professor of medicine and director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

He has spent more than two decades studying how environmental stressors including pollutants contribute to the risk of heart disease and other chronic conditions. More recently, Rajagopalan—also the Herman K. Hellerstein MD, Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at the school—has added geographic and spatial factors to his analysis.

Known for creative approaches to medical research, Rajagopalan leads a team that developed a novel way to analyze environments—from large urban areas to expansive rural locales—and predict the prevalence of coronary heart disease and other conditions.

Its tools: artificial-intelligence (AI) systems that extract visual features from satellites and street-view images—and then find patterns to make the predictions.

"We have pioneered the utilization of street view features in assessing cardiovascular risk," Rajagopalan and his co-authors wrote in a study recently published in the European Heart Journal. It's based on more than 500,000 images from nearly 800 census tracts in seven cities, including Cleveland.

The research team, which includes Zhuo Chen, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Rajagopalan's lab and the first author on the work, published a separate, similar study in JAMA Cardiology based on nearly 32,000 satellite images from the same cities.

"This is a really innovative way to try to do this type of research," said William Schiemann, PhD, vice dean for research and innovation at CWRU's medical school, noting that the approach could help with preventative healthcare and outreach initiatives.

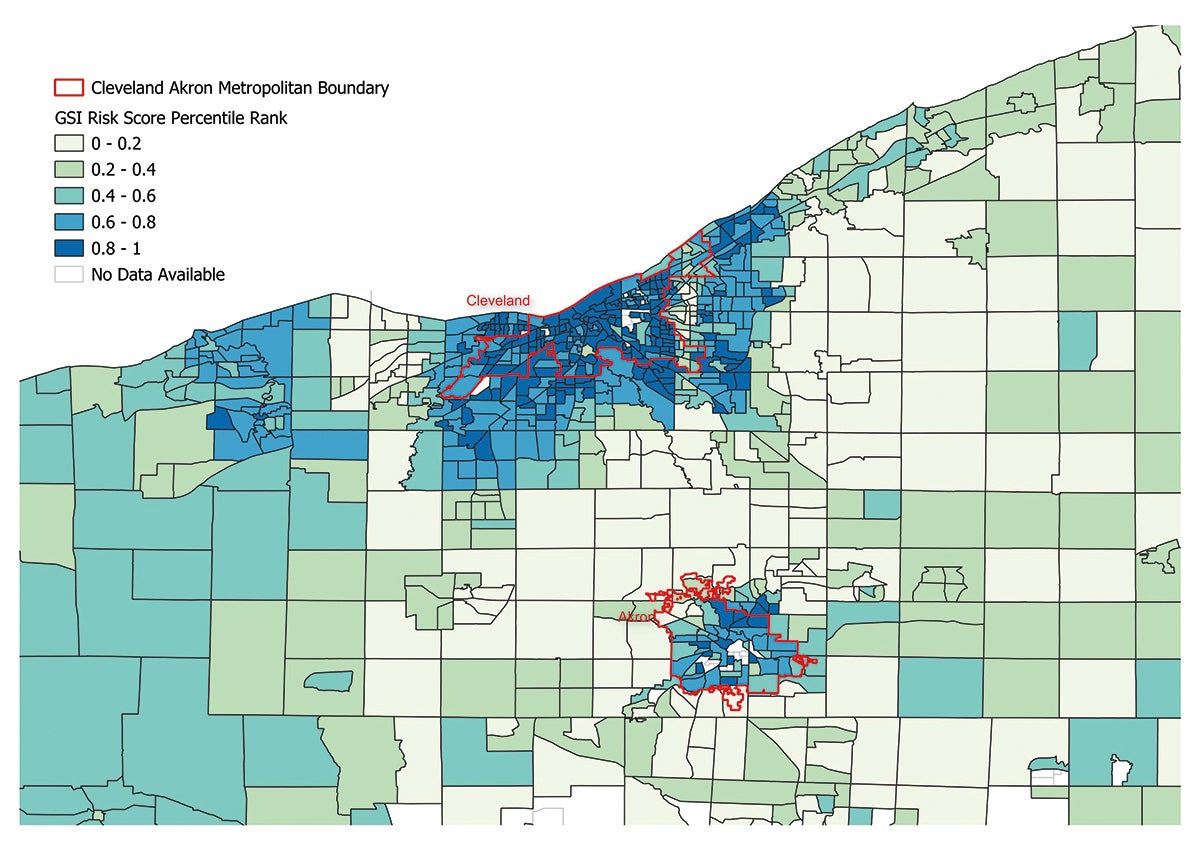

IMAGE COURTESY OF ZHUO CHEN OF SANJAY RAJAGOPALAN'S TEAMThis map shows areas in Northeast Ohio, including Cleveland and Akron, ranked by their risk score for cardiovascular problems, including heart attacks and strokes. The scores are based on satellite images analyzed with artificial intelligence, which assesses the neighborhood and environmental factors linked to these health issues. Darker areas

indicate higher risk.

IMAGE COURTESY OF ZHUO CHEN OF SANJAY RAJAGOPALAN'S TEAMThis map shows areas in Northeast Ohio, including Cleveland and Akron, ranked by their risk score for cardiovascular problems, including heart attacks and strokes. The scores are based on satellite images analyzed with artificial intelligence, which assesses the neighborhood and environmental factors linked to these health issues. Darker areas

indicate higher risk.

Researchers began their work by feeding the images into a computer vision model—that is, a software program able to detect, identify and classify potentially thousands of visual features from each image. They then trained complex computer models to use the features to predict instances of coronary heart disease and other chronic health conditions in neighborhoods.

Researchers compared those predictions to actual prevalence levels—and were encouraged by the strength of the correlations. They also produced maps highlighting areas with features more—or less—predictive of disease.

For example, one feature that highlighted roads, highways and railroads on these "heat maps" had a positive association with coronary heart disease, while another that highlighted recreational facilities had a negative association.

The researchers wrote in the JAMA article that their approach had the potential to identify vulnerable patient populations and high-prevalence areas and facilitate "targeted interventions and resource allocation for more effective prevention and management strategies."

The teams on the studies included researchers from CWRU, University Hospitals Harrington Heart and Vascular Institute and Houston Methodist Hospital. Rajagopalan is also chief of cardiovascular medicine and chief academic and scientific officer at the Harrington institute.

He sees tremendous prospects. Already, he said, there's increased interest in links between the external environment and chronic health conditions. And he envisions information gleaned from AI and computer-vision models being used by urban planners to design healthier neighborhoods and by physicians who combine environmental data with traditional health statistics to refine personalized predictions for chronic conditions.

"If you can use this approach to aggregate environmental features from large geographic areas using your laptop, and can do it to reimagine a healthier world," Rajagopalan said, "how powerful is that?"

— LYDIA COUTRÉ