LENS

Nourishing a Community

How researchers are working to eradicate 'food deserts'

Darcy Freedman

Cleveland shouldn't be in this position.

It has a bounty of urban farming, multimillion-dollar investments to increase healthy-foods outlets and a solid understanding of the connection between community well-being and convenient access to healthy food.

Yet more than half of Clevelanders live in so-called "food deserts," where the availability of affordable, nutritious foods is limited and people experience inequalities in economic opportunity and quality of health.

That disconnect has made Cleveland ripe for an examination of why efforts to increase food security are not working sufficiently—and what can be done differently.

A Case Western Reserve-led team is doing that research, thanks to a three-year, $936,000 Tipping Points grant from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, and matching grants from several local organizations and national foundations.

The researchers are taking a novel approach by building a computational model to help guide local decision-makers with simulations that test what real-world changes or combination of changes might best deliver broad improvements in Cleveland.

The model will take into account data and on-the-ground perspectives of local stakeholders as well as the many complex, confounding and interacting dynamics influencing a "local food system," which is the network that includes food production, distribution, purchases, consumption and waste.

Lessons learned here could be adopted in low-resource urban communities nationally.

"We are trying to figure out if there are tipping points in the [food] system that produce big impacts over time on outcomes such as food security," said Darcy Freedman, PhD, who leads the new research and is an associate professor in the School of Medicine's Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences and director of its Mary Ann Swetland Center for Environmental Health. "The simulation project will inform how best to sequence and integrate efforts to move the needle on some of the most intractable factors shaping food deserts."

The researchers know, for example, that having more grocery stores in underserved areas is important, but not sufficient.

But what if a community could reduce the number of households facing crises (ranging from homelessness to domestic violence), increase job-training initiatives or boost the use of savings accounts? Would some of these changes catalyze improvements in the number of people able to secure affordable, healthy food? And because people need money to buy food, the researchers also are using the simulations to find ways to improve economic opportunity.

Freedman said that once the computational model is completed and validated, researchers and community stakeholders will run simulations asking these kinds of "what if" questions.

While she recognizes the challenges in reducing stressors such as homelessness or unemployment, she said the goal "is to open our minds to think outside the box" and pinpoint how new initiatives could have a significant return on investment now and into the future.

Modeling Strategies to Improve Communities

Research by Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, The Ohio State University's John Glenn College of Public Affairs and Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City

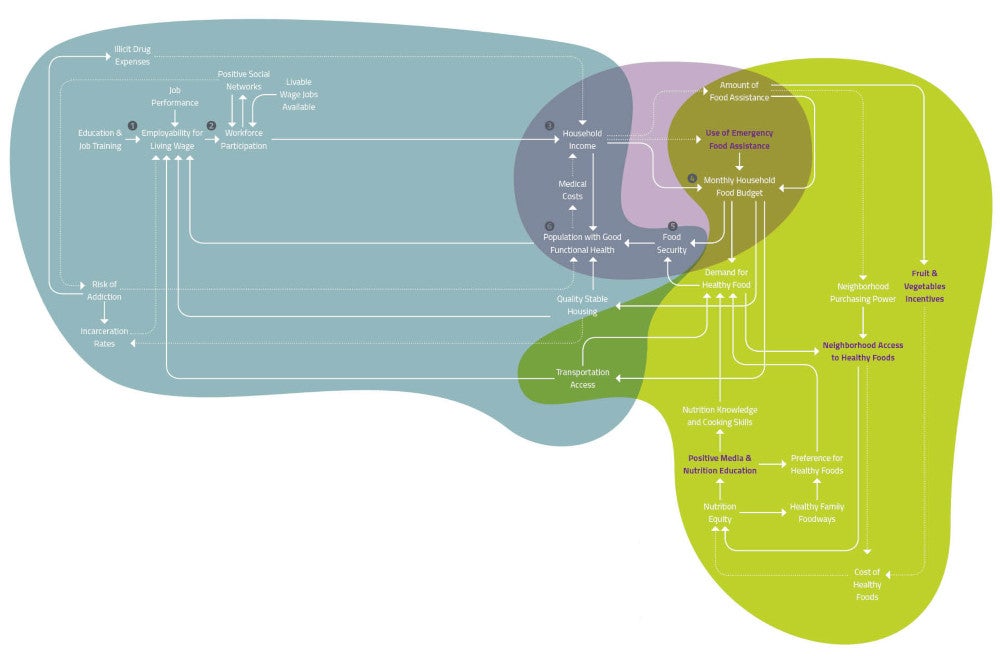

A COMPLEX ISSUE

While increasing the number of grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods is important, it isn't enough.

Researchers in a Case Western Reserve-led project are creating a computational model to better understand the many factors that can lead to improved economic opportunity, food security and nutrition equity, and run simulations to discover solutions that could have the most impact.

On paper, the variables—or levers—impacting these outcomes look like a constellation of connected dots that can be "pressed."

Consider an example in the graphic above: An increase in the number of people with the skills to secure a job paying a living wage (1) could in succession lead to: more workforce participation (2), higher household income (3), a larger household food budget (4), increased food security (5), more people with good functional health (6) and then back to more people in a position to obtain a living wage (1). Once the model is completed later this year, researchers will test different income levels—and countless other variables—in a series of simulations to learn which changes could best achieve food security and other outcomes at a community-wide level.

Three Outcomes to Maximize in the Computational Model:

LOCAL

50% of Clevelanders and 25% of Cuyahoga County residents live in a food desert, or low-income areas more than 0.5 miles from a supermarket.1

More than 137,000 Cuyahoga County residents live more than 2 miles from a supermarket.2

NATIONAL

54.4 million people—nearly 18% of the U.S. population—live in areas that are low income and have limited access to a supermarket or grocery store within 0.5 miles (urban) and 10 miles (rural)3

1 A 2017 Cuyahoga County Planning Commission report for the Cuyahoga County Board of Health

2 Cuyahoga County Board of Health

3 A 2017 report based on 2015 data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture

Infographic and artist's rendering of computational model by Mariana Cano