features

Pioneering Scientist

Paul Tesar explores the complexities of little-understood cells to revolutionize treatment of devastating neurological diseases

Illustration by Israel Vargas

Illustration by Israel VargasThe memory is indelible.

Paul Tesar stood at a podium ready to share his groundbreaking research on Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD), a rare, incurable genetic condition that progressively erodes intellectual and motor skills.

Facing the pioneering Case Western Reserve University scientist was a sea of expectant peers, intensely focused parents determined to know more—and children in wheelchairs or held in their caretakers' arms.

"I was not prepared for the fact that many kids with PMD were in the room," said Tesar, PhD (CWR '03), "I remember every detail."

Tesar and his colleagues are working as fast as possible to advance the science, ever mindful of the parents—like those who attended the medical symposium—for whom "it's not moving fast enough."

But the image most seared into Tesar's mind from that day in Wilmington, Delaware, nearly eleven years ago is of the children. Despite their inability to walk or talk, despite their surgeries or feeding tubes, they looked happy. "It's inspirational to see their ability to appreciate joy in life," said Tesar, who has a 9-year-old daughter. "It gives me additional motivation to do everything I can to provide them a better life."

Now that future may be drawing closer. CWRU recently created an institute that Tesar directs to deepen the understanding of the cellular underpinnings of PMD and other neurological diseases—and revolutionize treatments. The university also licensed a PMD drug Tesar's lab created to Ionis Pharmaceuticals, which recently reached a milestone with the launch of a clinical trial. The goal is to help young people with the condition regain a level of motor and intellectual skills.

"His research has changed the future for PMD and provided hope to families that didn't have hope before," said former longtime PMD Foundation Chair David Manley, whose 22-year-old son, Jaden, was diagnosed with the disease at 18 months. "Paul's work has life-changing implications."

A CLEAR VISION

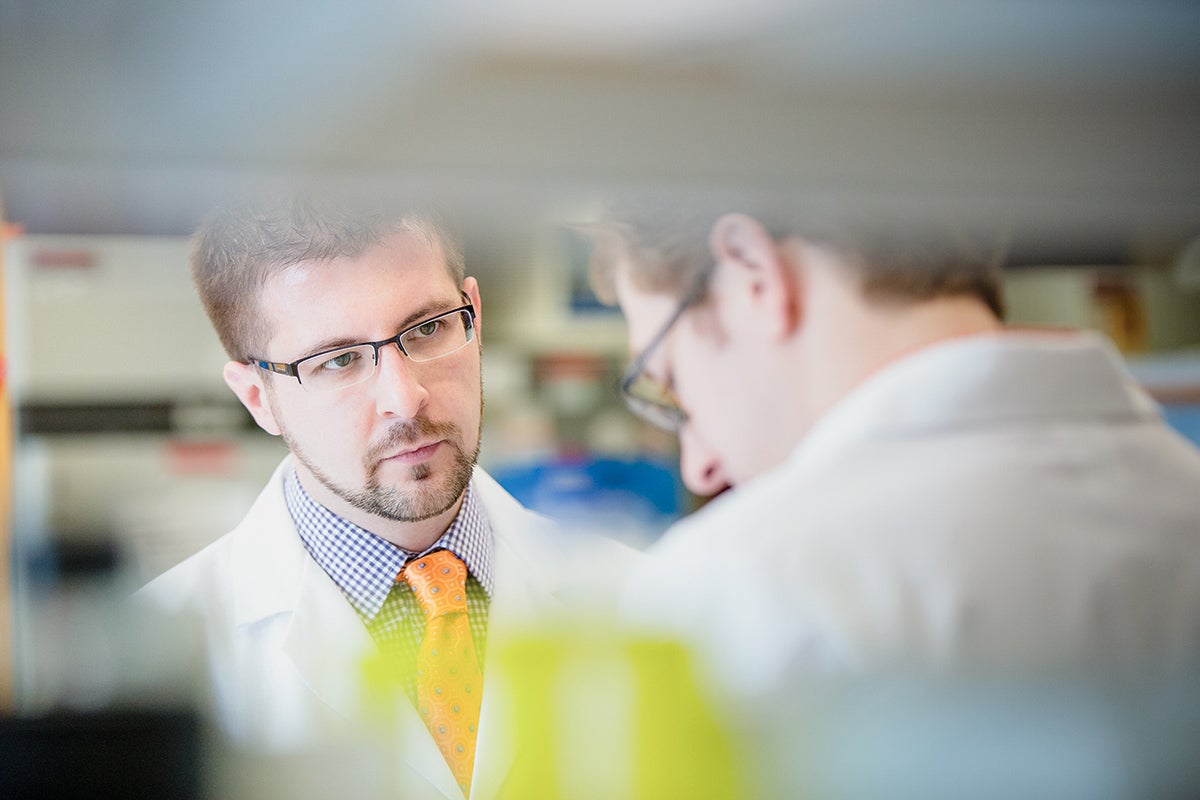

Paul Tesar is a trailblazing researcher and now leads CWRU's new Institute for Glial Sciences

Paul Tesar is a trailblazing researcher and now leads CWRU's new Institute for Glial SciencesTesar's energy seems inexhaustible. He runs a high-powered lab, publishes a constant flurry of research papers, co-founded a company based on campus research he and others are conducting, directs the university's new Institute for Glial Sciences, works as a mentor to scientists as well as Cleveland high school students and meets with families whose children have PMD.

The career of this scientist—officially known as the Dr. Donald and Ruth Weber Goodman Professor of Innovative Therapeutics in the School of Medicine's Department of Genetics and Genome Sciences—began when he conducted groundbreaking stem-cell research as a PhD candidate in Oxford, England.

It reached another milestone in November 2023, when the university announced the glial sciences institute to focus on cells that play a critical role in the health and diseases of the nervous systems, including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's, autism spectrum disorders, Parkinson's disease and cancer.

"He's in it for all the right reasons," said Ronn Richard, the former longtime president and CEO of the Cleveland Foundation, and Tesar's advisor and friend. "He loves research, and he's really driven by his desire to alleviate human suffering."

Richard, now a member of the CWRU Board of Trustees, was among those who assisted Tesar in his return to Cleveland after the award-winning doctoral work that could have taken him anywhere.

A Cleveland native, Tesar first came to Case Western Reserve as an undergraduate after an inspiring summer internship at Cleveland Clinic, where he had his first exposure to a research lab and realized science could be a career.

During his first year on campus, Tesar joined the lab of associate professor of biology Stephen Haynesworth, PhD, who specializes in mesenchymal stem cells (discovered at the university in 1987 by late biology professor Arnold Caplan, PhD). There, Tesar found himself at the heart of the booming regenerative-medicine field. "It was an exciting opportunity to be part of an ecosystem that was putting work developed at the lab into patients," he said. "That core essence of what I learned as an undergraduate has shaped the scientist that I am today and the way I run my research lab."

Tesar was so enamored of his undergraduate experience at CWRU—where he also met his wife, Anne (Wolbert) (CWR '03), now a physician's assistant—that he intended to pursue a PhD on campus. But advisors encouraged him to broaden his academic experience.

As he considered his next steps, Tesar received an invitation to apply to the National Institutes of Health Oxford-Cambridge (NIH OxCam) Scholars Program, established just a couple of years prior "to create leaders that will discover treatments and cures for diseases," said Richard, who was the founding chairman of the program's board. Tesar was one of just six applicants accepted that year.

Tesar secured positions with mentors at the forefront of their fields; at Oxford, he collaborated with Sir Richard Gardner, PhD. Knighted for his pioneering work in developmental biology, Gardner had established new techniques for performing microsurgery on mammal embryos, advancing ways to use stem cells for regenerative medicine. Tesar was among his most "outstanding" research students, Gardner recalled, as well as "a very nice person" with whom he once enjoyed an afternoon of clay-pigeon shooting.

At NIH, Tesar worked with Ronald McKay, PhD, whose research paved the way for using stem cells to treat conditions like diabetes and Parkinson's disease and delved into the genetic and developmental underpinnings of brain disorders. McKay was impressed by Tesar's systematic approach to research and his technical precision. "If you're a researcher, you're dreaming about something; you want to understand something that currently is not understood," McKay said. "And Paul had that quality." The research question Tesar addressed was whether stem cells from the early embryo could be harnessed to study the early processes of brain development, and then model later stages of brain disease. "Paul had a very clear idea of what he wanted to do and where he wanted to go," Gardner said.

At the time, the use of human embryonic stem cells was limited because they differed in unexplained ways from the mouse cells commonly used in research. But to maximize their potential, scientists needed to understand how to apply their mouse-cell knowledge to these stem cells.

Tesar's breakthrough discovery of an additional type of cell—epiblast stem cells from early mouse embryos—effectively bridged the critical gap. These cells closely resembled human embryonic stem cells, offering new insights into early development and the potential for regenerative medicine.

This research achievement led to Tesar's landmark paper in the prestigious scientific journal Nature and garnered him widespread acclaim. The British Society for Developmental Biology awarded Tesar the Beddington Medal, which celebrates excellence in developmental biology research among early-career researchers, in 2008. And the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center presented him with the Harold M. Weintraub Award, acknowledging exceptional achievements in the field.

THE CRUX OF THE MATTER

Paul Tesar

Paul TesarAs Tesar completed his degree at Oxford, CWRU medical leaders—including then School of Medicine Dean Pamela Davis, MD, PhD and current dean, Stan Gerson, MD—wanted him to come back.

In 2010, the university offered Tesar his own lab and Gerson, then director of the campus-based National Center for Regenerative Medicine, provided initial funding. "The opportunity was too good to turn down," said Tesar. He was just 29.

At the time, some biomedical researchers were focused on turning stem-cell populations into neurons to study Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, which Tesar found "exciting," he said, "but it was also what everybody else was doing. I wanted to do something different."

The human brain houses about 200 billion cells, approximately 100 million of which are neurons. The others are collectively referred to as glial cells, which were thought to keep all the neurons together. Scientists now know that glial cells have more specialized roles that regulate brain health, like removing damaged cells, supplying essential nutrients to neurons and fighting infection.

Despite the importance of glial cells to human health, few research centers globally are dedicated to their study. Tesar strategically chose to focus on glial cells to position his team to conduct science not pursued by others. Specifically, he studies oligodendrocytes, a type of glial cell that creates myelin, or the protective coating around nerve cells that functions like insulation, enabling electrical signals to travel throughout the brain while protecting the nerve cell.

When myelin is damaged, nerves degenerate, causing diseases of the nervous system. In certain rare genetic disorders like PMD, myelin is faulty from birth. Tesar devoted his lab to understanding why glial cells are dysfunctional in those diseases and developing potential medicines to fix or regenerate those cells.

His aim is to answer questions—and have an impact on people's lives. "The route to the patient runs through the private sector," said Davis, now a CWRU Distinguished University Professor and The Arline H. and Curtis F. Garvin Research Professor. Recognizing the need to translate his research into real-world applications, Tesar reached out to Richard and others for guidance on creating a startup company focused on a treatment for multiple sclerosis.

He proved a quick study. "As well as being a brilliant biomedical researcher, Paul is a natural businessperson and soon mastered the various aspects of starting a new biotech company," Richard said. Tesar and chemical biologist Drew Adams, PhD, an associate professor, recruited researchers and a board of directors, including Richard, committed to developing drugs for patients with myelin deficiencies.

In 2016, the collaborators and their funders launched Convelo Therapeutics. The company has since brought on 17 employees, secured more than $80 million in funding and forged ahead with developing treatments to offer hope to people with multiple sclerosis worldwide. "Not every scientific lab has to drive their science to translation," Tesar said, "but the meaningfulness to me is to take what we do and push it into patients where it's effective."

THE NEXT GENERATION

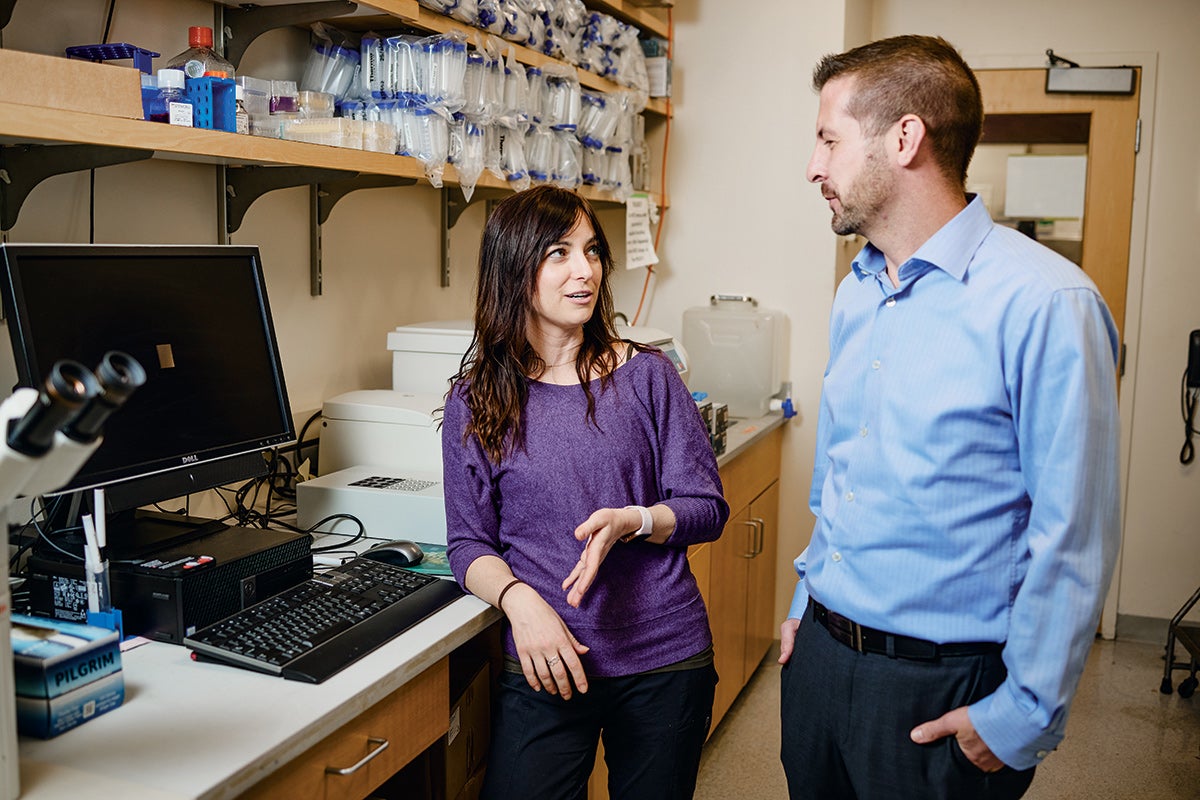

Photo: Angelo Merendino Marissa Scavuzzo, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Paul Tesar's lab, is studying how glial cells contribute to gastrointestinal health and disease, and won the 2023 Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology. The coveted prize is awarded jointly by the journal Science and Eppendorf SE, an international life-science company.

Now the research Tesar's team has conducted over 14 years with support from philanthropy and government grants will be taken to the next level. The Institute for Glial Sciences will have new faculty members working with Tesar on developing methods for studying glial cells and creating treatments.

"Guided by Professor Paul Tesar's exceptional leadership, we're uniting innovation with impact," Gerson said.

The institute will also offer education and training opportunities to students and postdoctoral and clinical fellows, vital to the future of this work. "When you have a rare disease like ours, there are so few people working on it that when those scientists retire or pass away, that work stops and the information may be lost," said Manley, the PMD Foundation's former chair. "Paul is perpetuating future generations of researchers."

Tesar has shown a deep commitment to training and educating. He has mentored 50 trainees, more than half of whom are women, he said, and nearly 20% are from groups historically underrepresented in medicine.

He "tailors his mentorship to each person, which is a sign of a great mentor," said Marissa Scavuzzo, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Tesar's lab who is studying how glial cells contribute to gastrointestinal health and disease. For that work, Scavuzzo was one of just 21 scientists nationally selected in 2021 to be a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Hanna H. Gray Fellow.

Tesar also helped Scavuzzo and her husband, Andrew, found the nonprofit Rise Up: Northeast Ohio. The program brings transformative learning experiences to high school students across Cleveland to engage in hands-on, cutting-edge science under the guidance of professional scientists.

The initiative's mission is close to his heart, Tesar said, and a way to pay forward the experience that first led him into biomedical research. "It's important," he said, "for high school students to know that science is a career path.

"In addition to his prestigious research awards, including the medical school's Case Medal for Excellence in Health Science Innovation in 2023, Tesar has received numerous campus and national awards for mentoring.

As Scavuzzo considered options for her post-doc research, she was aware of Tesar's reputation as an exceptional mentor and had been impressed by his research. However, it was something entirely different that attracted her to his lab.

"When I interviewed with Professor Tesar, he told me that coming back to Case Western Reserve was the best decision he'd ever made in his life," she said. "But then he stopped and said, ‘Wait a second. No; it's the second-best decision I ever made in my life. The first best decision I ever made in my life was marrying my wife.'

"It was an "aha" moment for Scavuzzo, who appreciated that a researcher with Tesar's career trajectory "still always makes space for the people that matter in his life," she said.

For Tesar, people come first, whether they're his own family, trainees, or patients and caretakers struggling with diseases like PMD.

"That first presentation to the families seems like both yesterday and a million years ago," he said. "I wasn't a father at the time, and when my daughter was born, I came a percentage of a step closer to understanding what some of those families are going through. I'm motivated to do everything I can to make new discoveries that can potentially help patients. That is what drives our science forward."

"Paul sees important questions and then figures out a way to get to the crux of the matter."

— Anthony Wynshaw-Boris, MD, PhD, the James H. Jewell MD '34 Professor of Genetics at the CWRU School of Medicine