lens

Turning Silver to Gold

Faculty in ancient languages and chemistry reconstruct a formula from the earliest days of alchemy

Undergraduate student researcher Aspen Slavick-Gierlach (left) explains to a visiting student how to "turn" silver into gold.

Undergraduate student researcher Aspen Slavick-Gierlach (left) explains to a visiting student how to "turn" silver into gold.

Holding her breath, Aspen Slavick-Gierlach dipped a wafer-size silver bar into a boiling mixture and then quickly lifted it out. The silver had turned gold.

"We screeched with excitement," said Slavick-Gierlach, a third-year undergraduate at Case Western Reserve University.

In that moment last fall, Maddalena Rumor, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Classics, knew that, after months of painstaking research and testing, they had finally reconstructed one of the oldest chemical instructions ever recorded.

Maddalena Rumor, an assistant professor in the Department of Classics.

Maddalena Rumor, an assistant professor in the Department of Classics.

"It was very meaningful historically," said Rumor, who had collaborated with Rekha Srinivasan, PhD (CWR '03), a senior instructor in chemistry, and students from their respective disciplines to decode what was written on a clay tablet thousands of years old. The work combined ancient knowledge and modern science, Rumor said, allowing them to "shed light on an area of history that would otherwise ... be inscrutable."

That history dates back 2,700 years to when the instructions became part of the renowned royal library of Assurbanipal in Nineveh (now Iraq). They were written in Akkadian, an ancient Semitic language, by pressing cuneiform signs into clay.

Rekha Srinivasan, the James Stephen Swinehart, PhD, Professorial Teaching Fellow in Chemistry.

Rekha Srinivasan, the James Stephen Swinehart, PhD, Professorial Teaching Fellow in Chemistry.

During the last 170 years, about 500,000 cuneiform clay tablets have been excavated, said Rumor, an historian of ancient Near Eastern medicine and technology.

And of those tablets, she said, two particularly drew her attention because each had chemical instructions no others contained. "They are unique," she said.

Each also offered a window into what would later become known as alchemy, an art based on the belief that materials could be transformed. One tablet included instructions for coloring base metals to resemble more precious ones, the other for inexpensively dying wool a deep purple, a color associated with royalty.

But neither tablet's contents had been fully understood—and the challenges abounded. The tablets were fragmented, portions of the instructions were gone and those that remained referenced terms, knowledge and methods now largely lost to time.

With a College of Arts and Sciences' Expanding Horizons Initiative grant, Rumor and Srinivasan hired students and visited the British Museum in London to examine what they call the "silver tablet," which they'd only seen in pictures.

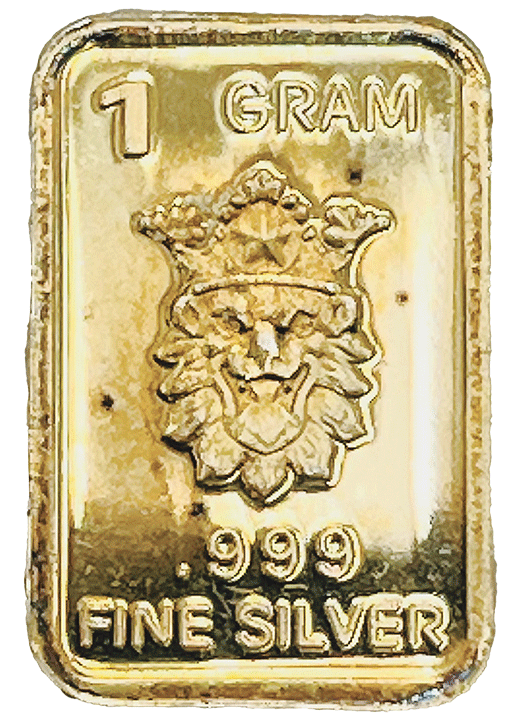

A silver bar shining gold, after being dipped into a treatment made from an ancient formula.

A silver bar shining gold, after being dipped into a treatment made from an ancient formula.

When Rumor held it, she saw traces of a sign meaning silver. "We knew then," she said, "that the ancient scribe meant to transform silver into something—but we didn't know what exactly."

Back on campus, the researchers tested chemical combinations and processes to puzzle out what was done to the silver, reviewed the historical context of available chemicals, methods and tools and continually refined their interpretations.

They eventually understood the formula to involve a mixture of sulfur, limestone and natron in water that is then heated. The silver bar emerged from that solution looking like shiny gold. "The result was stunning," Rumor said.

Srinivasan, the James Stephen Swinehart, PhD, Professorial Teaching Fellow in Chemistry, said she now understands first-hand that, while "everybody thinks alchemy is this magic, [it] is actually the earliest form of experimental chemistry."

The team is working to replicate the second tablet's instructions.

Despite the tablets' explicit 2,700-year-old warning to not show the recipes to anyone, Rumor and Srinivasan are presenting their work at academic conferences.