LENS Health and Wellness

Fighting Disparities

Cancers Hit Certain Populations Harder than Others, and Researcher Monica Webb Hooper Wants to Know Why

Monica Webb Hooper, professor

Monica Webb Hooper, professor

Monica Webb Hooper, PhD, is a professor of oncology, family medicine and community health, and psychological sciences at Case Western Reserve. She's passionate about health and social justice—and the overlap between them, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities and low-income communities struck disproportionately by diseases including cancer and obesity. That's why she was eager in 2016 to become the inaugural director of the Office of Cancer Disparities Research at the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. She talked to Think about what she hopes to accomplish, why her work is more urgent than ever and what she's learned about disparities.*

What makes something a cancer disparity?Disparities are differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality and/or survivorship of cancers. For example, African-Americans are significantly more likely to die from breast cancer, prostate cancer and lung cancer than the general population. Of the top four cancers—lung, breast, colon and prostate—three of them have distinct disparities by race.

Why do you think that is?That's the million-dollar question. Broadly speaking, socio-economic conditions—things that affect how we live, work and play—account for the biggest variance in why health disparities exist. For instance, if you live in a neighborhood that is poor, you are bombarded with messages on billboards or corner store signs, advertising for tobacco use, liquor or the lottery. That, combined with oppression, unemployment, underemployment, discrimination and other factors, may encourage self-medication for forms of distress with substance use or a behavior like smoking. It's complicated.

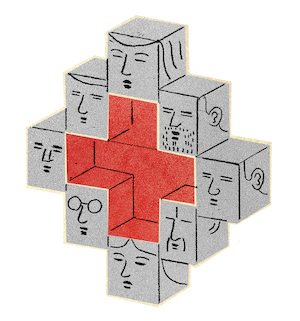

IMAGE: DAVID PLUNKERT/THEISPOT

IMAGE: DAVID PLUNKERT/THEISPOTBecause of the prevalence and lethality of it. My first research experience in clinical health psychology was working in an HIV lab and looking at the effects of stress-management interventions on health outcomes. But when I learned that tobacco causes more deaths than HIV, suicide, homicide, terrorism—all these things combined—I figured that if you're really concerned about the health of a community, you need to focus on smoking. And if tobacco is not a priority on the agenda, then you've failed.

You moved from the University of Miami to start research at Case Western Reserve. What drew you to Cleveland?There was an opportunity that I was super excited about, and that was to establish and lead an office of cancer disparities research. I also direct a research lab called the Tobacco, Obesity and Oncology Laboratory, which is part of the cancer center and School of Medicine. We focus largely on disadvantaged populations and test the impact of cognitive behavioral therapy in groups and individual sessions, [and] via telephone for individuals unable to travel to the university. We also conduct basic psychological studies to inform methods to improve tobacco treatment efficacy.

How do you start to put interventions into practice within a community?It is a challenge. Community trust is something that institutions across the country—and here is no different—certainly have to focus on and build. We have an amazing cancer center community advisory board, which serves as a trusted link and voice for the larger community. One of the keys is showing individuals that you're here for the long haul. You're not just here for one project. You're volunteering in the community, you're at community forums, you're doing things that are sometimes not at all related to your research. We also engage in "community-based participatory research," in which community stakeholders are true partners and have a chance to teach investigators about their community rather than the reverse.

*The conversation was edited for length.