“These fossils also provide new insights into the common ancestor from which human and ape family trees diverged millions of years ago.”

Redrawing Evolutionary Trees

Two hominid skeletons, found by Case Western Reserve experts, get us steps closer to understanding mankind's roots

This year, Case Western Reserve University researchers, along with colleagues from across the country and around the world, uncovered two human ancestors who each provide invaluable insight on humans' evolution from tree climbers to upright walkers.

This year, Case Western Reserve University researchers, along with colleagues from across the country and around the world, uncovered two human ancestors who each provide invaluable insight on humans' evolution from tree climbers to upright walkers.

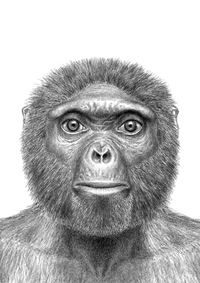

At 4.4 million years old, Ardi, short for Ardipithecus ramidus, is mankind's oldest known relative and was designed to live both in the trees and on the ground.

"This skeleton sheds light on a time period we hadn't understood well before," says Scott W. Simpson, PhD, an associate professor of anatomy at the School of Medicine, who co-authored three of the 11 papers on Ardi. "These fossils also provide new insights into the common ancestor from which human and ape family trees diverged millions of years ago."

The small female skeleton represents a species in transition—adept at climbing but able to walk on two legs. Simpson called her a "quantum leap in understanding." The journal Science heartily agreed, naming Ardi its "Breakthrough of the Year" in 2009.

Fast-forward 800,000 years from Ardi and you'll find another human ancestor, this one with his feet planted firmly on the ground.

The hominid partial skeleton is nicknamed Kadanuumuu, which translates as "big man" in the Afar language of the Ethiopian Afar region, where he was found. At nearly 5 feet 5 inches tall, he towered over both Ardi and another famed hominid—his great-great-great-etc. granddaughter, Lucy.

At 3.2-million years old, Lucy, like Kadanuumuu, belongs to Australopithecus afarensis species. Found in 1974, she had been the oldest example of full upright walking. Kadanuumuu, however, proves that human ancestors were walking at least 400,000 years before her time—evidence previously only known through 3.6-million-year-old footprints.

"Nearly 1 million years before humans' ancestors started making stone tools, they already had long legs similar to modern humans," says Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD, the curator and head of physical anthropology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and an adjunct professor of anatomy, anthropology and cognitive sciences at Case Western Reserve, who was involved in both the Ardi and Kadanuumuu discoveries and interpretations.

What's more, he says, is that Kadanuumuu's shoulder complex was more like humans' and not at all like chimpanzees', effectively debunking the idea that humans ever went through a knuckle-walking phase.

See more of the picture: Read more in Medicus and Think.