lens

Skin Deep

Developing a test to detect Parkinson's early

IMAGE Courtesy of the Zou Lab

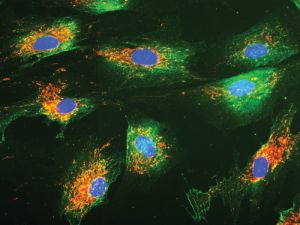

IMAGE Courtesy of the Zou Lab Wenquan Zou's lab uses fluorescent dyes to help visualize under a microscope the molecular deformities in skin cells that could indicate the presence of Parkinson's disease. The blue ovals are nuclei, while the surrounding areas in green and orange are proteins and mitochondria.

Parkinson's disease can be developing for decades by the time symptoms become evident—with a definitive diagnosis coming only after invasive spinal taps or, later, from autopsied brain tissue.

But Case Western Reserve University researchers are now leading a collaboration to develop a skin test for early diagnosis—which could lead to early treatment and potentially prevent some irreversible brain-cell damage.

"Given that skin tissues are much more easily accessible than brain tissues,this approach will be useful for diagnosing patients, monitoring disease severity or evaluating therapeutic efficacy in clinical trials," said Wenquan Zou, MD, PhD, a professor of pathology at the School of Medicine and associate director of the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center, based at the university.

Wenquan Zou

Wenquan Zou

The researcher's proof-of-concept study was published in September in the American Medical Association's JAMA Neurology.

Zou and collaborators have received a five-year, $3.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to develop their revolutionary approach: a diagnostic method that uses a tiny sample of skin to detect disease biomarkers, notably deformities in central nervous system proteins essential for proper functioning of brain cells. Zou's research colleagues include Zerui Wang, MD, PhD; Shu G. Chen, PhD; and Steven Gunzler, MD, from the medical school.

The funding was followed by a two-year grant of about $150,000 Zou received from the Alzheimer's Association, Alzheimer's Research UK, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research and the Weston Brain Institute. That grant's research involves using similar skin-testing methods to diagnose different degenerative brain diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

With both grants, Zou is testing the skin of more than 300 individuals who died of Parkinson's or Alzheimer's, or are living with either disease, to validate the diagnostic method.

If the work is successful and researchers receive regulatory approval, clinical skin tests might be available in three to five years for both conditions, Zou said.