lens

A Medical Treasure Trove

CWRU museum preserves transformative devices and instruments—including many invented by faculty and alumni

Amanda Mahoney

Remarkable stories unfold in the public museum galleries and research vaults at Case Western Reserve University’s Dittrick Medical History Center: the quest to improve disease diagnosis, advances in surgical procedures, the development of contraception.

With thousands of artifacts—more than can possibly be displayed—the Dittrick offers an intriguing record of the evolution of modern medicine.

“It’s a treasure trove,” said Amanda Mahoney, PhD, the Dittrick’s chief curator.

The pioneers whose technology is preserved at the museum include medical researchers with ties to CWRU and its predecessor schools.

Read on to learn about just a few:

GOLDBLATT CLAMPS FOR HYPERTENSION EXPERIMENTS, 1934

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRU

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRUHarry Goldblatt, MD, was a professor of experimental pathology at Western Reserve University School of Medicine who devised blood-vessel clamps that enabled groundbreaking research.

He wanted to understand the connection between high blood pressure and hardening of the arteries that carry blood to the kidneys—and why patients frequently have both.

“Your kidneys play a really important role in managing blood pressure; they maintain fluid balance,” Mahoney said. “But how exactly they do that is very complicated.”

In laboratory research, Goldblatt’s clamps constricted blood flow—creating the effects of hardened arteries—which, in turn, caused a chemical chain reaction leading to hypertension.

By detailing the chemical mechanism, Goldblatt conducted “crucial research,” Mahoney said, that made possible the work of other CWRU scientists, including Leonard T. Skeggs Jr. (see below), and laid the groundwork for the medications used today to manage blood pressure, reduce the risk of stroke, heart attack and heart failure.

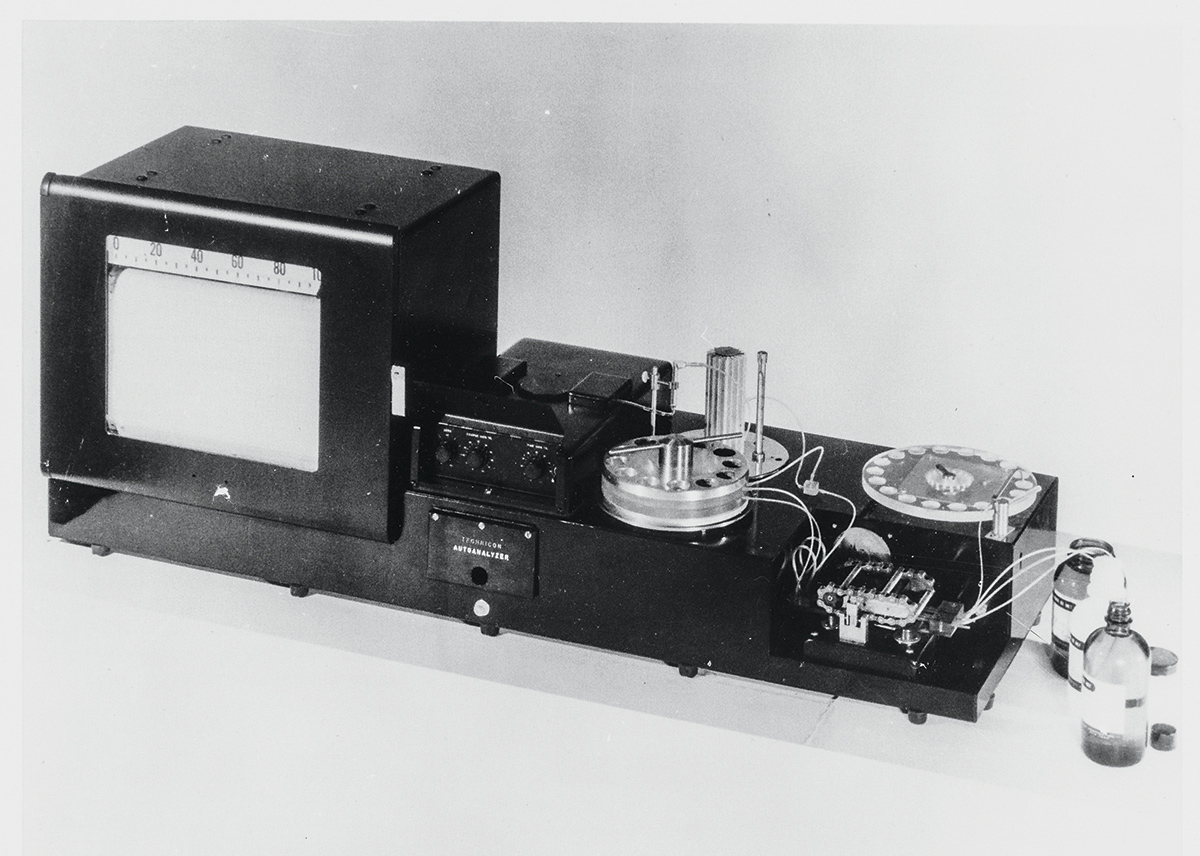

CONTINUOUS FLOW AUTOMATED ANALYZER, 1957

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRU

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRULeonard T. Skeggs Jr., PhD (GRS ’41, ’48, biochemistry), invented a machine to analyze the chemistry of multiple blood samples by processing them in a continuous flow instead of one by one.

At the time, Skeggs ran a clinical chemistry lab at a facility affiliated with what’s now the CWRU medical school and wanted a way to process routine tests more reliably and efficiently.

In a flash of inspiration, he envisioned running the tests in an automated, flowing stream. The challenge: how to separate the blood specimens. His creative solution was to insert a bubble between each one.

“This technology is amazing,” Mahoney said. “It dramatically sped up the lab.”

What’s now called the Technicon AutoAnalyzer II is still sold by SEAL Analytical, which credits Skeggs as the inventor and calls it “the world’s best known and most successful continuous flow automated analyzer.” Today, it is mainly used for a very different purpose: analyzing the chemical composition of water, soil, food and wine.

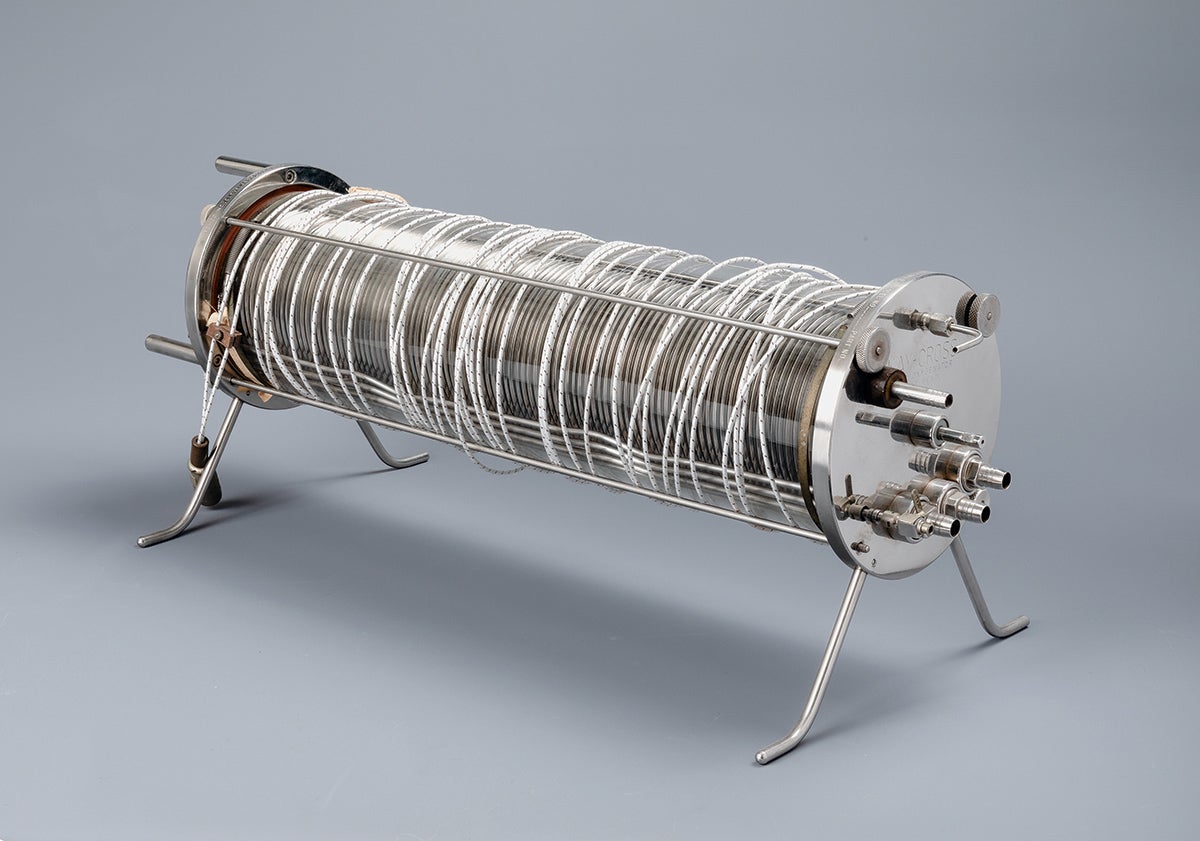

KAY-CROSS DISC OXYGENATOR, 1958

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRU

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRUIn the mid-20th century, Cleveland was a major center of still-precarious open-heart surgeries. And vital to their development was a technology developed locally—but now largely forgotten.

This new kind of “oxygenator” was a component of heart-lung machines and it was developed by a St. Luke’s Hospital team that included three medical school faculty, among them cardiothoracic surgeon Frederick S. Cross, MD (MED ’45).

Cross and fellow surgeon Earle B. Kay, MD, also were the first to use the device during open heart surgery.

Oxygenators do work performed by the lungs, allowing red blood cells to absorb oxygen and release carbon dioxide. In the cylinder-shaped Kay-Cross machine, slowly rotating Tefloncoated discs created very thin layers of blood that maximized the exchange of the two gases.

The device’s design was adaptable to different operating room needs, and its durable components could be frequently cleaned and sterilized.

“This practicality made the device a better tool for open-heart surgery compared to more scientifically advanced oxygenators,” Mahoney said. “Surgical teams from across the country came to Cleveland to learn how to use it.”

PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY (PEG) FEEDING

TUBE, 1979

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRU

PHOTO COURTESY OF DITTRICK MEDICAL HISTORY CENTER, CWRUJeffrey Ponsky, MD (MED ’71, MGT ’90), now a professor emeritus at the School of Medicine, and Michael Gauderer, MD, devised a simple, practical way to insert feeding tubes without opening the abdomen—and it all started with the glow of an endoscope.

Ponsky, then a University Hospitals (UH) surgeon and endoscopist, was using the device—a tube with a light and camera at the end—to examine the stomach of an infant patient of Gauderer’s, a UH pediatric surgeon.

In the dimmed operating room, the endoscope lit up the stomach from within. Gauderer was intrigued. Could an endoscope guide a feeding tube into the stomach without a more invasive surgical procedure that carried more risks?

He and Ponsky devised a way. They inserted a guide tube into the stomach through a small incision in the skin and used it to snare and snake a feeding tube—attached to and guided by an endoscope—down through the esophagus and into place.

The simple, low-risk procedure became a highly effective way to hydrate and feed patients who can’t safely swallow food. And the easily managed feeding tube made it possible for many sick children to live at home, Mahoney said.

“Such a simple technology might not seem cutting edge,” said Mahoney, drawing a parallel to the Kay-Cross oxygenator (see above). “But often it’s the simple or practical solutions that make the most impact.”

The PEG feeding tube is now widely used in adults and children throughout the world.

— BARBARA BROTMAN