FEATURE Engineering, Science, and Technology

Image-ination

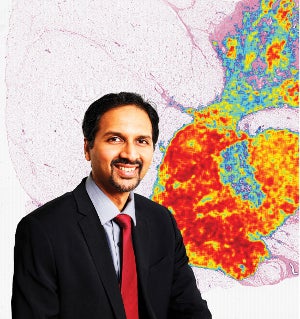

Anant Madabhushi Discovers How Images of Our Cells Can Unlock Keys to Personalized Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

Photo Illustration with Photography by Roger Mastroianni; Background image courtesy of Andrew Janowczyk and Anant Madabhushi.

Photo Illustration with Photography by Roger Mastroianni; Background image courtesy of Andrew Janowczyk and Anant Madabhushi.Anant Madabhushi has uncovered clues in images of cancerous cells that could improve disease diagnosis and prognosis, and lead to better treatment recommendations. Now he aims to take his innovation global. The breast-cancer image behind him is the result of a machine-learning algorithm developed by his group to identify invasive breast cancer on tissue scans.

A lanky boy stands beside a noisy highway, thumb up and arm outstretched. He needs a ride—10 kilometers from the last stop on the train line to his rural university, where he’s studying the fledgling field of bioengineering.

For four years, twice a day, he holds out his hand—when not risking his life on the public bus—relying on the kindness of strangers to help make his dreams come true. Eighteen years later, Anant Madabhushi, PhD, has fulfilled many of his youthful aspirations. The F. Alex Nason Professor II of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve University, he is founding director of a center that could lead to a global leap in personalized cancer diagnostics.

For Madabhushi, that long trek from his home to Mahatma Gandhi Mission’s College of Engineering outside Mumbai, India, reinforced the importance of relationships to reaching goals and the understanding that success comes from working with others. But for those who know the story, it also offers an early window into the personal drive and innovative spirit that have led to his achievements as a scientist, mentor and entrepreneur.

Madabhushi directs a team of 35 at the Case School of Engineering’s Center for Computational Imaging and Personalized Diagnostics, which he founded in 2012. The center’s mission: to uncover data invisible to the human eye that can help physicians and scientists differentiate a healthy tissue from a cancerous one. Madabhushi’s goal is to improve disease diagnosis, treatment response and prognosis for a range of cancers. The first beneficiaries likely will be women with the most common type of early onset breast cancer who, whether they live in Cleveland or Mumbai, could obtain nearly instantaneous diagnostic results that could help determine appropriate therapies.

It’s the prospect of his innovation improving the health of patients across the globe that lights up his eyes and, as many colleagues note, drives him to work harder and longer than most anyone else they know.

“He’s a special guy,” said Michael Feldman, MD, an early collaborator of Madabhushi’s. “He’s got the passion, the enthusiasm, the desire and, as my grandmother would say, he’s a mensch—has a decent soul.”

COLORFUL COLLABORATION

Feldman laughed when reminded of the moment Madabhushi made him wait in the rain.

It was 2002, four years after Madabhushi had traveled from India to the United States to pursue a master’s degree at the University of Texas at Austin. He was now a doctoral candidate in bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania. And he was looking at radiologic scans with the help of computer algorithms, essentially programmed math recipes, that enabled faster and better ways to make accurate disease diagnoses and predict disease outcomes using large networks of computers. Feldman, a pathology professor at the University of Pennsylvania who was interested in improving prostate cancer detection, crossed the lab and asked the bioengineer if he wanted to see something cool and colorful: It was a microscope slide containing a tissue sample.

“I told him you can’t really see prostate cancer at a cellular level with radiology—there’s not enough resolution—but if you want to see what that looks like, here it is,” said Feldman. “In radiology, every-thing is black, white and shades of gray. In pathology, it’s all the color information.”

Feldman asked if Madabhushi could use his process for teaching the computer to recognize cancer patterns on black-and-white MRI scans by taking advantage of the rainbow of information available in pathology slides.

To do that, the computer first needed to learn more about recognizing cancer. So the two men matched cancerous areas on images of pathology slides with corresponding regions on each patient’s MRI. Then Madabhushi programmed and trained the computer to recognize the cancer in the MRIs based on Feldman’s expertise.

A week later, Madabhushi messaged Feldman, saying he had results to share. Feldman replied: “Let’s meet at 8 a.m. tomorrow.”

“I remember it so vividly because it was pouring, and I was a little late getting there, and he was standing outside the building with his umbrella,” Madabhushi said, a touch of horror in his voice more than 14 years later. “I made the MD wait.”

In the Penn engineering computer lab, Madabhushi pulled up a probability map in colors from blue to red showing the likelihood the computer could detect cancer. In those colors was success—the computer had indeed learned and could predict, by looking at the non-invasive MRIs, the prostate regions with cancer.

“I saw the future of pathology,” Feldman said. “I saw what we do and what we’ve done for the last 100 years, which is mostly descriptive and opinion-based, be converted into something that is quantitative and reproducible.”

The validation and perspective from the clinicians at Penn propelled Madabhushi into the field of translational medicine, taking theoretical or academic concepts and creating new diagnostic tools or treatments for patients. His contact with patients—an uncommon interaction for biomedical engineers—was further motivation. “I realized it’s not just a scan, it’s not just an image, it’s an image that came from this patient,” he said. “It was quite an eye opener.”

It was success born out of collaboration and camaraderie. In 2012, Madabhushi received a patent, along with Feldman and John Tomaszewski, MD, chair of the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences at University at Buffalo. The work and friendships endured even as Madabhushi moved away from Penn into faculty positions first at Rutgers University and then at Case Western Reserve. Said Feldman, “This collaboration will go on until we die.”

PHOTO: Roger Mastroianni

PHOTO: Roger MastroianniEvery Friday, Anant Madabhushi and his team of 35 students, post-docs and faculty meet for lunch and discuss their research.

GRAB A SLICE

No one here goes hungry on Fridays.

That’s when Madabhushi gathers all members of his center together. He carries in pizzas, which they grab by the plateful as they settle in to spend time with colleagues and discuss their projects.

Since 2005, when he was at Rutgers, he has gathered his team over food to share friendship along with the challenges, breakthroughs in their research and new scientific literature. On Dec. 16, Madabhushi marked the 300th meeting of what he calls his Friday Literary Guild.

“We have really smart people, but sometimes they need to build confidence,” Madabhushi said. Undergrads learn to present their projects before research fellows, as biomedical engineers working on breast cancer annotations chime in to offer suggestions about brain cancer detection.

While Madabhushi, 41, is building a career as a preeminent expert in personalized cancer diagnostics, he’s also building up the people around him. He describes himself as the conductor of a very talented symphony. “You can’t do this unless you’re part of a team, because you can’t know everything,” Madabhushi said.

That’s why, when Case Western Reserve recruited him for a position, he insisted the university also provide support for all members of his lab who wanted to follow him. All 12 said yes.

To that base, he’s added past collaborators and a host of colleagues he’s met in Cleveland, including Hannah Gilmore, MD (MED ’03), associate professor of pathology at the School of Medicine and director of surgical pathology at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

Even before he arrived on campus in 2012, Madabhushi started conversations with Gilmore, whose breast cancer expertise complemented his research. Gilmore was equally excited to find a collaborator who could amplify her breast cancer detection work through biomedical engineering.

Now, nearly every week, Gilmore grabs a cup of coffee and walks to the engineering school's Wickenden Building. Sitting beside the biomedical engineers, she helps them teach the computer what cancer tissue looks like and, when the computer gets something wrong, she helps the engineers understand why. That’s why Madabhushi came to the university: to find an environment that mimicked the collaborations he had at Penn and then make that environment available to all his students. The mentorship is succeeding. Nate Braman, one of the center’s graduate students working with Gilmore, mirrors Madabhushi’s enthusiasm for translational medicine. “The thing that makes me most passionate is the knowledge that the work I’m doing has impact way beyond the work I’m doing today,” Braman said.

Jeffrey Duerk, PhD (GRS ’87, biomedical engineering), dean of the Case School of Engineering, is extremely excited by the center’s results and especially proud of how Madabhushi mentors students.

“The people who train under him don’t come out being mini-me’s of Anant,” he said, “but come out being their own individuals with their own perspectives on where this research can lead.”

BREAST CANCER BREAKTHROUGH

Of all his innovations, there is one closest to his heart.

It’s an image-based, risk-score algorithm for estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer, the most common form of early-onset breast cancer. Madabhushi developed the algorithm with collaborators while he was at Rutgers. But when he couldn’t obtain federal grants for the breast cancer work as an academic researcher, he started the company Ibris Inc. in 2010 to pursue small-business innovation grants.

“If you’re a successful professor, you’re like a CEO,” said James Monaco, PhD, co-founder of Ibris and a former research fellow in Madabhushi’s Rutgers lab. “You’re able to see the very top-level strategy; you are very good at selling your message to other people and communicating.”

Two years ago, Monaco and Madabhushi concluded their search for an investor when Inspirata, a digital pathology and cancer diagnostics company in Tampa, Florida, acquired the assets of Ibris.

Mark Lloyd, PhD, executive vice president and founder of Inspirata, said he was attracted by the breast cancer algorithm and the opportunity to work with Madabhushi.

“There is a very well-defined sweet spot in which you have world-class expertise—like Dr. Madabhushi and the rest of the team he has put together—as well as the kind of the product that can be impactful,” Lloyd said.

Last summer, the federal funding for breast cancer work that had eluded Madabhushi for eight years materialized in the form of a $3.3 million, five-year, academic-industry partnership grant from the National Cancer Institute. It was for Madabhushi and his team, including Inspirata, Feldman, Gilmore and others, to develop further and verify the algorithms. Lloyd said they have multiple additional grant applications pending, and expect the breast-cancer product to be available to clinicians by 2019.

If approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the algorithm could be available to any oncologist with an Internet connection who has the ability to make and scan a pathology slide. Once the image is uploaded to the computing cloud, algorithms look beyond what a pathologist’s eye can see; they examine texture, shape and structure of glands, nuclei and surrounding tissue to determine the aggressiveness and risk associated with the breast cancer. This information allows oncologists to make more-informed treatment recommendations.

“[I]t turns out 80 percent of these cancers will actually benefit from what is called hormonal therapy alone; they don’t require chemotherapy,” Madabhushi said in a 2016 presentation.

A genomic test already exists that can help identify which patients would benefit from chemotherapy. It is available primarily in the United States, destroys the tissue, can take two weeks for results and is sold for about $4,000. Madabhushi’s algorithms instead could provide a diagnostic tool accessible worldwide that takes only minutes and leaves the tissue untouched and available for further testing. He expects the manufacturing cost for each test could be as low as $4, while the sale price might be around $200.

“This could have an impact for a woman in Sydney, Australia; in Doha, Qatar; in Freetown, Sierra Leone; or in Cleveland, Ohio,” he said. Where it could have the greatest impact is in countries like his native India, where, he said, treatment medications such as chemotherapy are scarce and need to be directed at patients who will benefit from them. While this innovation is closest to the marketplace, Feldman said he expects in the next 10 years to also see clinical availability of computer-assisted diagnostics in ear, nose and throat cancers, lung cancer and kidney disease—all outcomes of Madabhushi’s vision and collaborations. “There are many things we’re working on right now that could be profoundly transformational,” Madabhushi said, “and I want [my students] to know that. I see it as a great motivator: It’s not just a paper, it’s not just a patent. … This could be useful information that a clinician could use to change the way they manage or treat patients.”

Read about Anant Madabhushi's recent work to identify breast cancers on digital tissue slides.

The Madabhushi Symphony

Photos Courtesy of Anant Madabhushi

Anant Madabhushi with his parents, Ramaswami and Jalaja

Aditi Madabhushi, Anant Madabhushi’s sister

Anant Madabhushi with his wife and son, Annapurna and Advait.

Anant Madabhushi insists that his success is the result of the researchers he “conducts” in what he calls his very talented symphony—and family members who have provided crucial support behind the scenes his entire life.

THE PROFESSIONAL SIDE

Madabhushi founded the Center for Computational Imaging and Personalized Diagnostics in September 2012. Its 35 members have published 75 journal articles, received 23 patents and brought in $15 million in grant funding. The center focuses on image-based detection, diagnosis, predicted treatment response, and prognosis of breast, prostate, oral, head and neck, brain, rectal and lung cancers.

THE PERSONAL SIDE

The players who Madabhushi said have sacrificed for him and provided inspiration: His parents, Ramaswami Madabhushi, a mechanical engineer, and Jalaja Madabhushi, a PhD in maternal and child nutrition; his sister, Aditi Madabhushi, MD, a vascular surgeon at Cincinnati VA Medical Center; his wife, Annapurna Valluri, PhD, director of investments at University Hospitals; and their 6-year-old son, Advait.