features

Their Aim is True

Known as ‘bent arrows,’ these students changed direction to pursue MDs

As mortar fire flew toward his military base, Luke Flint sat in a cramped bomb shelter in Afghanistan, his head down. Using his cellphone for light, he began studying—not for a mission, but a medical school admissions test.

“I didn’t want to sit in a bomb shelter for 1½ hours and waste that time,” he explained.

Now a first-year medical student, Flint is one of Case Western Reserve University’s “bent arrows,” a term applied to those whose paths are less direct than many of their peers.

John Caughey, MD, coined the term nearly 80 years ago. As the medical school’s first assistant dean of students, he pioneered the recruitment of such nontraditional applicants.

“Our school was one of the first to really start building diverse classes with people who wrote different chapters in their lives” before choosing to become physicians, said Lina Mehta, MD, associate dean for admissions and a professor of radiology. Whatever twists and turns they may take on their way to medical school, she said, “they’re going to ultimately hit their target.”

They also bring skills and perspectives—not to mention a degree of maturity—that enrich the educational experience for themselves, their peers, instructors and future patients.

For Flint, juggling the rigors of medical school and the hubbub of life with kids can be tough. But perspective is always close at hand.

“I think back to studying by cellphone light in a bomb shelter,” he said. “I have gone through way too much to turn back now.”

Here are the stories of Flint and some of his fellow bent arrows.

Brock Montgomery

Second-year student

As an algebra teacher, Brock Montgomery used the connecting cubes he’s holding, known as manipulatives, to explain abstract concepts to students in concrete ways.

For Brock Montgomery, the turn began while shadowing a physician in a pediatric emergency room.

A baby, struggling for oxygen, was wheeled into the emergency room on the mother’s lap. The healthcare team immediately began suctioning the nose and mouth, saving the infant’s life.

“That was just mind-blowing,” said Montgomery, then a middle-school teacher in St. Louis, Missouri, considering a career change. “I thought, ‘This is something I can do, too? I can save lives for a living?’”

The next day, he signed up for premed courses at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Despite the seeming differences between his past and future professions, Montgomery has found many of his earlier experiences relevant. He may not have ever given a patient a terminal diagnosis, but he often had to tell parents their children were failing and needed help.

His previous career has helped him improve the experience of his fellow students, too: During “anatomy boot camp,” when students gather around a cadaver to identify structures, Montgomery suggested his teammates give a thumbs up once they had the answer rather than blurting it out, so everyone had the chance to think through the problem for themselves—a trick the husband and father of two young sons learned back in his old job.

“Every med student should spend a week in [a K-12] classroom,” he said.

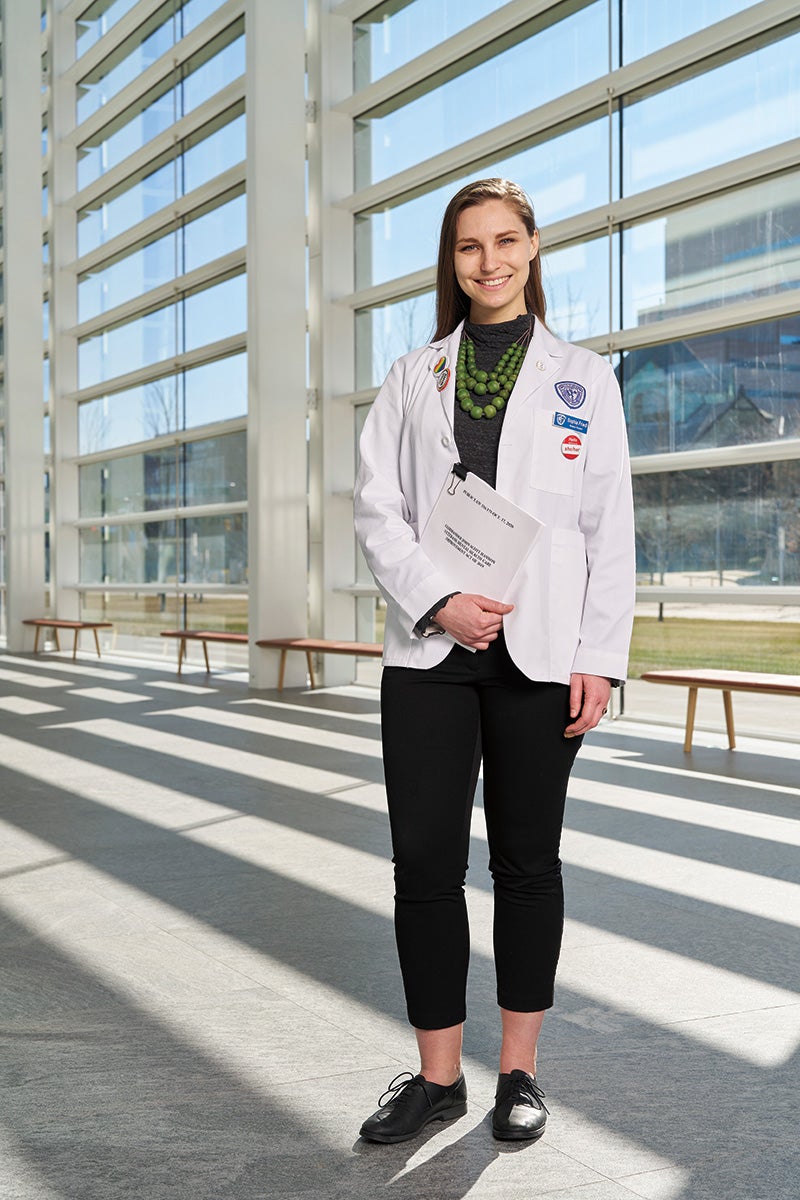

Sophie Friedl

First-year student

Sophie Friedl played a key role in drafting federal legislation to improve veterans’ mental healthcare. She’s holding a copy of the 2020 law.

When the COVID-19 pandemic erupted in 2020, Sophie Friedl found herself deeply troubled by reading news accounts of healthcare workers succumbing to depression and suicide.

“I could see the attrition rate was going up,” she said. “It was almost like a call to service.”

Friedl had already spent her several years working to improve healthcare for veterans. As a legislative assistant on Capitol Hill, she played a lead role drafting the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act, signed into law in 2020.

When the pandemic shut down much of the country, she was lobbying the White House and Congress on behalf of the American Psychological Association to improve mental-health services for veterans and active-duty military.

But working remotely on health policy wasn’t enough. So, she left her job, picked up some part-time lobbying and began taking premed classes. At night, she did psychiatric intake evaluations at a local hospital.

— Sophie Friedl

“It didn’t feel that the work I was doing was as important as taking care of folks who had COVID,” she said. “This was my shot to replace the providers we were losing.”

Friedl, who’s also earning a master’s degree in bioethics and medical humanities at Case Western Reserve and is engaged to a U.S. Army infantry officer, hopes to work for the Veterans Health Administration as a physician.

She’s already sharing what she knows about veterans’ health issues: When a Vietnam vet and liver-transplant recipient spoke to first-year students in February, Friedl used a messaging app to share real-time information with classmates about veterans’ illness rates and the services available to them.

“I’m able to put a lot of what I’m learning into context,” Friedl said, “and understand how it translates to the real world.”

Maira Bhatty

First-year student

Maira Bhatty with the leather portfolio she used when meeting with clients as a financial and investment advisor.

In 2018, Maira Bhatty checked into Carle Hospital in Champaign, Illinois, expecting twins and afraid of needles. She came out with two healthy boys (now age 4), determined to become a doctor.

Despite hailing from a family of physicians in Lahore, Pakistan, Bhatty had never considered a career in medicine. She’d taught financial economics and statistics to undergraduates and MBA students in Lahore, and later reinvented herself as a financial and investment advisor after moving to the United States with her husband. Then came the monthlong hospitalization for a high-risk pregnancy.

But the doctors and nurses who cared for her were so kind and supportive—and the biology of her condition so fascinating—that she decided to pursue medicine after all.

“Those experiences exposed me to a side of healthcare I hadn’t [seen] before,” said Bhatty, who quit her job and began volunteering in the same neonatal intensive-care unit where her own babies spent several days. “I felt a sense of purpose,” she remembers thinking as she held infants whose parents couldn’t always be there. “This is what I really want to do.”

Now, explaining complex material to fellow students reminds her of teaching. And talking with clients about sensitive financial questions helped prepare Bhatty to gather patients’ social and medical histories. “It feels comfortable,” she said.

— Maira Bhatty

Bhatty hopes to one day provide free medical care to needy patients in Pakistan, where she still has family. In the meantime, she is mentoring other bent arrows to help them achieve their own medical ambitions.

“I want to help students who want to become physicians in whatever way I can,” she said.

Luke Flint

First-year student

Luke Flint with the bullet-proof vest he wore as a U.S. Air Force combat meteorologist in Afghanistan.

Sometimes, Luke Flint daydreams about being in a U.S. Air Force helicopter watching wild camels racing across the deserts of Afghanistan—an indelible experience he felt privileged to have.

Flint spent six years as a combat meteorologist forecasting battlefield weather. But medicine “was something scratching at the back of my head, like I had unfinished business,” he said.

He had taken a few college classes but lacked the discipline to continue and enlisted at age 22.

Years later, his interest in medicine was rekindled when he was stationed at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where special-forces medics are trained. By the time Flint left the ser- vice in 2019, he was well on his way to a premed degree. He had also married and had a step-daughter, now age 12. (The couple also have a son, age 20 months.)

Learning to parse complex weather data for Army brass turned out to be good preparation—especially for the medical school’s InQuiry sessions, when small teams of medical students gather under the supervision of a faculty member or a more senior student to teach each other about patient vignettes. During one session, Flint helped his fellow students understand how food moves through the digestive tract, even though it wasn’t his turn to present.

“They said my explanation made it a lot more clear,” he said.

He’s also seen how his military experience could prepare him for a potential career caring for veterans. While working at a pain-manage- ment and rehabilitation clinic near Fort Bragg, he felt the kinship of a common experience with patients—most of them former service members.

“Having a provider around capable of speaking the language is a real service to them,” Flint said.

Alexander Richards

First-year student

Alexander Richards with an oar blade, but not one he took to Tokyo for the Olympics in 2021.

During his final race as a member of the U.S. men’s Olympic rowing team at the 2021 Tokyo games, Alexander Richards felt himself becoming one with his teammates in the boat.

“My job was to contribute to the cohesion of the crew,” he said. “I had to follow the person in front of me and make it easy for my teammate behind me. When we all worked together, we became something greater than the sum of our parts.”

Richards’ appreciation for the power of cooperation has proved directly relevant to medical school.

— Alexander Richards

“The necessity of teamwork and collaboration is really true across rowing and the curriculum that Case Western Reserve has built,” Richards said. “You can do all the preparation [possible], but you will never be able to do everything on your own.”

During team InQuiry meetings, Richards often finds himself achieving the kind of flow state he experienced while rowing as part of a crew: “The group will gel and find a perfect harmony where everyone is teaching and learning from one another,” he said. “When it happens, we all reach a higher level of understanding than any one of us could individually.”

Since high school, Richards had dreamed of rowing at the Olympics and becoming a physician. After graduating from Harvard University, he competed for the U.S. national team for three years while preparing for medical school.

“The week I submitted my med school application,” he said, “was the same week I made the Olympic team.”

Richards, who is engaged to a fellow rower, acknowledges that medical school can sometimes be a grind. But the years of intense training taught him to maintain the joy and savor the improvements that come from hard work.

“I enjoy what I’m doing because of the perspective I got from rowing, ” he said. “And I’m able to do it day after day because of the work ethic I gained from my training.”