FEATURES Law and Public Policy

Citizen Capers

The 103-year-old Trailblazer Still Speaks Out on the Power of People

PHOTO: GUS CHAN/ THE PLAIN DEALER/ ADVANCE MEDIA

PHOTO: GUS CHAN/ THE PLAIN DEALER/ ADVANCE MEDIA

Two minutes before showtime on a Sunday afternoon in June, Jean Murrell Capers (EDU '32) slips into her seat at a local radio station, trading her light pink straw hat for a set of headphones.

She is immaculately dressed in a black suit and flat, sensible shoes that make her look more petite than she already is.

At 103 years old, the retired judge and Cleveland icon remains as she ever was—genteel, determined and passionate about citizens' rights. In 2014, Capers joined community activist Art McKoy's on-air show, perhaps because she never warmed to the idea of retiring.

On this particular June evening, the first phone call is from the mother of a recent homicide victim, a 24-year-old black man shot days earlier outside a bar on Cleveland's West Side. His death weighs on Capers and, after a few more calls, she returns to it.

"I just regret when I hear a story like that, that I hadn't had the opportunity to meet him and know him, his friends," Capers tells McKoy.

"They are the ones who stand on our shoulders. That's why our shoulders must be in the right direction." Capers has spent a lifetime with her shoulders set squarely forward, cutting a path of progress and accomplishments, while reaching back to lift up others who followed.

In 1949, Capers became the first African-American woman elected to Cleveland City Council. In the mid-1950s, JET magazine—then the country's leading black weekly magazine—called her "the country's No. 1 Negro woman Democrat." In the 1960s, she was among the leaders prodding the city to make more racial progress. And in the 1970s, she became a local judge.

"There's no one else like her in Cleveland's local civic life," said Plain Dealer columnist Phillip Morris, who has written about Capers more than a dozen times during the last decade. "She's a cultural, social and intellectual treasure."

Capers recently sat for a series of interviews with Think magazine. We look back at what defined her and how she helped define her community.

UNWAVERING SUPPORT

"My parents were the ones who taught us who we were individually, the five of us. We were the best. That's what they emphasized to all of us."

Eugenia "Jean" Mae Murrell was 6 years old in 1919 when her parents, Edward E. and Dolly Ferguson Murrell, moved from Kentucky to Cleveland.

They wanted to provide their five children an integrated education—something Edward never experienced.

Edward and Dolly met as students at the State Normal School for Colored Persons (now called Kentucky State University), initially were teachers, and raised their children to value education, equality, the power of laws in everyday life—and the ability to impact those laws at the voting booth.

"Since our parents were Americans, then we were entitled to all the rights and privileges as enunciated in the Constitution of the United States," Capers recalled, her voice crisp, measured and emphatic. "We were entitled to those on the same level as any other students. Because somebody said that you weren't as good an American as anybody else, that didn't make it true."

These beliefs instilled self-confidence and taught the Murrell children to persevere in the face of racist encounters—whether from prejudiced high school teachers or institutions they held in high regard.

In 1929, Jean Murrell entered Western Reserve University's School of Education on an academic scholarship for a three-year program designed to prepare students to become elementary school teachers.

Capers recalled being one of only a handful of "Negro" students in her class, holding tight to a term that fell out of fashion years ago because, as she put it, "Black is a color; we were persons."

She enjoyed her education. But in her last year, with the prom nearing—and slated to be held off-campus—a list of African-American, female seniors was posted on a school bulletin board with instructions for them to see the assistant dean, Capers recalled.

Baffled and humiliated, Capers and her classmates wondered what they had done wrong.

"The [assistant] dean told us we were not to attend the annual prom," she said. "We knew about prejudice because it was in our everyday living. But for Western Reserve, the prestige and culture that it represented—why, it was just shocking."

Capers and the other students talked with their parents and conferred with others in the community. In the end, she said, she attended with a date from Adelbert College. She danced and enjoyed herself.

"There was nothing brave about it. I was a citizen," she said. "I was going to school to get rid of ignorance."

PHOTO: THE WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY, CLEVELAND, OHIO

PHOTO: THE WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY, CLEVELAND, OHIOIn the 1930s, Jean Murrell Capers played on a Cleveland recreation basketball team sponsored by Councilman Lawrence O. Payne. Capers is in the back row, far left, while her sister, Alice, is in the front row, far right.

REINVENTION: PART 1

"I was going to be a lawyer and I was going to run for public office."

Jean Murrell received her diploma in 1932. A high school standout in tennis and basketball, she soon began teaching health and physical education in the Cleveland schools.

But within a few years, she considered teaching "a sort of routine profession which didn't suit my temperament at all," she later told The Afro-American, a national weekly newspaper chain.

Murrell set her sights on something that had long drawn her interest: a seat on Cleveland City Council.

Because her ward councilman had a law degree, Murrell determined she needed the same credential to avoid lowering the standards for the office and to better know the laws and their deficiencies.

At the time, lawyering didn't fit prevailing views of fine womanhood, but that wasn't the point. "The only way people could help themselves was through the laws they passed," she said. "I wanted to be part of the profession where the laws were made."

REINVENTION: PART 2

Murrell also reset her personal life; she and her first husband divorced after a few years of marriage.

To avoid another mismatch, Murrell began telling all potential new suitors up front about her aspirations.

"I was going to be a lawyer and I was going to run for public office," she'd tell them. "Some of them dropped out because of that."

One man, however, was not intimidated or deterred.

Clifford Capers was a busboy at a hotel restaurant who supported her career choice.

Their different backgrounds and chosen vocations weren't an issue for either of them. "He was a hard worker," she said. "I was looking for somebody who had a job."

In 1943, they married, and she became Jean Murrell Capers.

She continued to work, and the money he made helped put her through law school.

Clifford Capers worked at the same hotel for more than 60 years, eventually becoming superintendent of services; the couple was together 53 years before his death at 91. They had no children, a deliberate choice. Capers knew she could make a bigger impact on young people with a career in public service than she could as a parent.

A CALLING TO PUBLIC SERVICE

"I am not in what you call politics; I am a student of government. There's a big difference."

The year Capers married, she launched her first bid for Cleveland City Council as a write-in candidate.

"Other than my parents, who encouraged me to run, most [others] said, 'No, don't run,'" she said. There had never been a black female member of city council.

She lost.

In the next six years, she ran and lost two more times. Meanwhile, Capers received her law degree in 1945 from what's now Cleveland State University's Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, passed the bar exam and set up her practice in the two-family home on East 40th Street where the couple lived with her parents. She took on mostly civil cases. In subsequent years, she worked at a law firm and became an assistant prosecutor.

In 1949, Capers fought and won her fourth campaign. Although raised in a Republican household, she ran against the incumbent as a Democrat, perhaps becoming the first black woman on the city council of a major U.S. city.

She also became well known for fighting against segregation in Cleveland and nationally (often traveling on behalf of the advocacy group National Council of Negro Women, of which she continues to be a member).

It was in 1955 that JET called Capers "the country's No. 1 Negro woman Democrat" since the death that year of Mary McLeod Bethune, the educator and civil rights leader who founded the National Council of Negro Women. The two women had been friends for years, and Capers even accompanied Bethune to tea at the White House with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

PHOTO: THE WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY, CLEVELAND, OHIO

PHOTO: THE WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY, CLEVELAND, OHIOJean Murrell Capers in the 1950s after becoming the first African-American woman on Cleveland City Council.

PROPELLING A CITY FORWARD

"If we were going to have a Negro mayor—why, then, we had to take it in steps, just like anything else."

Capers' tenure on City Council ended after she lost to a candidate in 1959 who secured more favor with the local Democratic Party.

But she didn't shrink away. She became an assistant Attorney General for Ohio, and later a special assistant to the AG. And she pivoted and helped make history.

While accounts vary about Capers' role in the Cleveland mayoral race in 1965, she and the League of Non-Partisan Voters, which she organized, have been credited with urging Carl Stokes to run in 1965 as an independent candidate. He lost, but the exercise helped position Stokes for victory in 1967—a win that made him the first black mayor of a major American city.

Capers epitomizes the civil rights and black political movements during the 1960s, said Ronald B. Adrine, JD, presiding judge of Cleveland Municipal Court. His list of examples includes encouraging the Stokes mayoral bid, working with the publisher of the Call & Post newspaper to bring about positive change in the black community and being active in Republican politics when the GOP still was viewed as the party of Abraham Lincoln.

Much of that activism stems from her willingness to counsel younger generations—just like her parents. "She still feels very strongly about that; it was all about the importance of reaching back, to get others and to groom them," said Adrine, who served on the bench with Capers.

Capers had joined the municipal court in 1977 when Ohio Gov. James Rhodes, a Republican, appointed her to the bench. She was elected outright the following year, serving until 1986.

During different points in her career, Capers experienced both support and a cold shoulder from Democrats and Republicans alike.

Meeting the needs of constituents, however, was what mattered most to her.

When Anita Laster Mays, JD, ran for a position on the Cleveland Municipal Court, Capers advised her to forgo traditional political gatherings in favor of street club meetings. "She showed me how to win as an underdog," said Laster Mays, who said she visited everyday voters at locations ranging from bus stops to bars. Laster Mays was elected in 2003 and now sits on the Eighth District Court of Appeals of Ohio.

NOT SO RETIRING

"You're not upholding your country and doing everything you can for it when you don't vote. And that is the most important part of being a citizen."

Ohio voting stickers are affixed on either side of the black briefcase Capers carries like a purse. She plans to vote in the national election next month, once again seizing hold of a right that women in the United States didn't have until ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, the year she turned 7.

It's a legal right—like so many others—that Capers prized as the daughter of Edward and Dolly Murrell and carried with her as a lawyer, councilwoman and judge.

Age limits forced Capers to retire from the court at 73. But retirement was a misnomer; she returned to her law practice, specializing in elder law well into her 90s.

Capers didn't close her law practice until after suffering a stroke. In 2012, she moved into an apartment at Judson Manor, where her younger sister—Alice Murrell Rose (GRS '58, education), a former teacher—lives. Alice's husband and fellow alumnus, Paul E. Rose (GRS '58, education), died in 2010.

A contingent of friends makes sure Capers stays on the go, whether it's to church service at Holy Trinity Baptist Church, a luncheon or an alumnae chapter meeting of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc. And she still offers visitors a spirited smile, her views on contemporary issues and a firm handshake.

The honors she has received—including an honorary degree from Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, awards from the National Bar Association as well as the Ohio and Cleveland bar associations, induction into the Ohio Women's Hall of Fame and most recently into the Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame—reflect what her pioneering career has meant to those who have followed.

"She rightfully credits herself in the knowledge that, for well over half a century, she was part of the political and civic life of Cleveland," Morris, the newspaper columnist, said. "I hate the word iconic, but she is iconic."

Notable relatives of Jean Murrell Capers include:

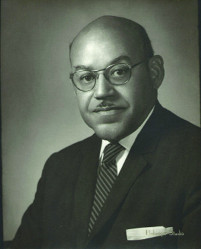

George R. Ferguson Jr.

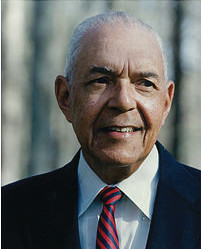

William Ferguson Reid

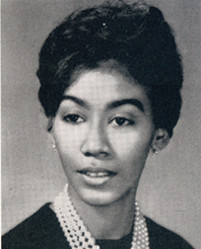

Olivia Ferguson McQueen

PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF OLIVIA FERGUSON MCQUEEN AND WILLIAM FERGUSON REID

PATERNAL UNCLE

Howard Murrell (1875-1926) was instrumental in Edward and Dolly Murrell's decision to move their family to Cleveland. He had already established himself as manager of the black-owned Empire Savings & Loan.

MATERNAL UNCLES

David Arthur Ferguson (1875-1935) was a dentist and the first black person to pass the Virginia State Board of Dental Examiners. He also was a founder and first president of an organization for black dentists that ultimately became the National Dental Association.

George R. Ferguson Sr. (1877-1932) became the first black physician in Charlottesville, Virginia.

MATERNAL COUSINS

George R. Ferguson Jr. (1911-1993) was president of the local chapter of the NAACP in Charlottesville, and led efforts to desegregate the University of Virginia hospital as well as local schools.

William Ferguson Reid (born 1925) was a surgeon and in 1967 became the first African-American elected to the Virginia General Assembly in the 20th century.

Olivia Ferguson McQueen (born 1942), the daughter of George Ferguson Jr., was a leader in the Charlottesville Twelve, a group of students who were plaintiffs in a successful court case in 1959 that mandated the integration of Charlottesville city schools. In 2013, she received her official diploma, 54 years after finishing high school.

Additional research by Sydney Otto and Kaitlin Murphy