FEATURE Epiphanies

Moments of Transformation

What Helps Make Us Who We Are?

The experiences that irrevocably change our lives can happen in an instant. These inflection points can be obvious—the trip that opens up a new perspective on the world's complexity, or subtle, such as a throwaway line from a friend that leads to dramatic changes that become clear only in retrospect.

Regardless of how they happen, these pivotal moments are so powerful that they divide our lives into "before" and "after." We talked to eight Case Western Reserve faculty members who recall the times that changed the way they live, work or pursue their passions. The stories that appear here are distilled from longer conversations.

The Moment When…

I REALIZED I COULD GO TO COLLEGE

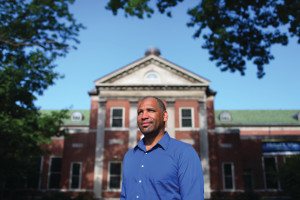

Emmitt Jolly, PhD, is an associate professor of biology.

I went to a small, poor middle school just outside of Tuskegee, Alabama.

One year, the counselor at school, Mrs. Mildred White, called me from the lunchroom and told me I had the highest math scores she'd seen. She asked what I wanted to do when I grew up. I said I thought I'd be a janitor or maybe an electrician. She told me I should think about becoming an electrical engineer. I knew that meant college, which wasn't something my family could afford. That was when she told me about scholarships. I had never heard of this thing that would help you pay for school.

From that moment on, she had me come to her office just about every week. She taught me chess. I showed her my poetry. She became a true mentor and introduced me to someone at Tuskegee University, where I eventually went to college.

There are lots of people in this world who are happy to make you feel good about yourself, but people like Mrs. White provide true support and direction to help you get to the next level.

Mrs. White moved me from blue collar to white collar. She moved me from working in the cotton fields to working in the laboratory.

I know how much mentors matter because of Mrs. White, and it's why I try to be a mentor today. It's why I'll never be someone who only does science. What really matters are the people whose lives you touch.

Mrs. White's mentorship changed my life. In December, I spoke at her funeral. I hope to be able to pay her efforts forward.

The Moment When…

I DISCOVERED THE POWER OF LEVERAGING PASSION TO SOLVE BIG PROBLEMS

Rebecca Darrah, PhD, is an assistant professor of nursing.

I went to college, knowing I really wanted to challenge myself. At the time, biology made sense to me and math made sense to me. Chemistry was the hardest thing I could imagine. But I liked the idea of taking the hardest classes and succeeding in them.

I did figure out how to do chemistry—I just didn't like it. When I took a biochemistry class, I realized that was a better fit. I switched my major and ultimately pursued genetics. I realized there was no reason to pursue something just because it's the hardest thing you can imagine. You choose something because you're genuinely interested in it.

What I didn't realize is that almost any topic can be challenging and have interesting problems to solve. The thing I love about genetics and biology is the way we can translate what we find to patients and make a real difference.

For example, I've been part of a larger project where we take patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) who are really, really sick and patients with CF who are less sick, and compare the genomes between the two groups. We look for differences that might help us find therapeutic targets that could help minimize the impact of CF on sicker patients.

In the end, I think a larger lesson I learned is to always have a deeper "why." In general, it's not enough to ask scientific questions just to ask them, in the same way that it's not enough to do something just because it's difficult. I want to make sure I see the larger context of the work.

The Moment When…

I UNDERSTOOD THE POWER OF COLLABORATION

Stanton Gerson, MD, is director of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Twenty-nine years ago, [CWRU biology professor] Arnie Caplan, PhD, walked into my office and asked me to explain hematopoietic stem cell differentiation [the process of specific stem cells turning into specific kinds of blood cells]. The conversation moved from blood-forming stem cells to bone-forming stem cells [known as mesenchymal stem cells].

We both realized that there were potential therapeutic applications, and that conversation led to a near 30-year collaboration. I helped him develop the therapeutic applications that led to the first five clinical trials using mesenchymal stem cells. [Those trials have had promising results for patients with a range of conditions.]

That experience has been important in the way I think about having people work here at the cancer center. So often, people are told to pick an area to focus on and stay with it and don't change, and I think that's baloney. If you don't think outside the box, you don't get very far.

For example, I introduced Rong Xu, PhD—who's an expert in identifying medications developed for one purpose that might be used for another—and Analisa DiFeo, PhD, an ovarian cancer expert. I thought they could test a drug Rong identified that had previously proved effective in animal studies of ovarian cancer.

It's critical that people cross-fertilize, and that's something that's much more possible at a university because of the diversity of our expertise. We talk about transdisciplinary research—getting people in different fields to talk through something and think up something. That's where the best ideas always come from.

The Moment When…

I REALIZED HOW TRAVEL COULD TRANSFORM LIVES

Deborah Jacobson, PhD, is an assistant professor of social work.

When I was in college, I did a study abroad program in England, traveled around Europe and spent a month in Israel. I fell in love with traveling.

After years of teaching, I became director of international education at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences in 2007.

My real transformation happened that same year, when I took students to India for the first time.

People talk about India as a land of contrasts. It's true. In big cities, you'll see a Lamborghini next to ox-driven carts, ancient temples next to modern high-rises and mansions next to slums.

But the contrasts are more than superficial. For example, because there's no social safety net, like Social Security, many people live in dire poverty.

I have continued taking students to India for short-term courses to learn about the culture and role of non-governmental social-service organizations. When we visit the public hospital, students see people waiting days just to get primary care. The facilities are dirty—bathrooms are covered in urine, and sometimes cats and dogs are in the buildings.

Yet not far away, there's a private hospital with beautiful architecture and perfect cleanliness. It's a place where people from oil-rich Middle Eastern countries get procedures like liposuction.

It's hard for students to know in advance how they're going to feel. We process our experiences most nights, and many people cry. Some feel guilt and shame [about their own relative privilege].

They come home and use resources differently, like using less water in the shower. They give more to their community, both in time and money. Sometimes career paths change; I know mine did.

The Moment When…

I LEARNED TO ASK QUESTIONS

Jennifer Carter, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

When I started college, I thought I wanted to build amusement parks as a Disney Imagineer [engineer]. I was taking engineering classes, but I also had a side job in the university's theater department. At one point, a friend asked why I wasn't working with an engineering professor.

I was a sophomore, and it hadn't even occurred to me that I could contribute to an engineering faculty member's research. My friend pointed out that all I had to do was ask.

So I did. I was taking an introductory materials class, and the faculty member went out of her way to share examples of the cool research being done in each area. I went up to her and asked if I could help with research. She said: "I thought you would never ask, but I'm so glad you did. Congratulations, you have a job."

That was it. I worked on a project linked to materials for rocket engines, and I loved everything about it. That opportunity changed my entire career path.

This kind of epiphany is actually very common in this area because we never really know about all the opportunities out there. I try to harness my experiences to encourage my students to ask questions—ask for what you need or what you want, and ask questions of the world around you.

I know that if I can get students to ask questions about what they see, they will find an excitement they never knew they had—because they didn't know what they didn't know.

The Moment When…

I CREATED NEW KINDS OF QUESTIONS THAT MATTERED

David Cooperrider, PhD (GRS '86, organizational behavior), is a Distinguished University Professor and the Fairmount Santrol - David L. Cooperrider Professor in Appreciative Inquiry.

Years ago, I developed an approach to scholarship called "Appreciative Inquiry [AI]." It is a way of designing questions that allows us to dream and devise big ideas together, instead of focusing solely on problems. It can quickly bring out the best in people and has been adopted by businesses worldwide.

In 1998, the Dalai Lama and others were developing a forum to bring leaders of all the world's religions together in dialogue, and his assistant asked if I would design and facilitate the events—and develop five opening questions.

I immediately thought, "This is way out of my league."

But I felt it would be a huge privilege.

For two full weeks, I developed those questions. I'd write them, then throw them away. I'd write them again and throw them away. I knew how critical it was. If the questions were right, miracles were possible. The first, for example, asked participants to describe a time when they saw clarity about their life's purpose. I wanted them to connect with each other's faith traditions. Imagine seeing the Dalai Lama ask a Greek Orthodox bishop the questions.

The event was a success. It changed my life to work with so many remarkable people.

Our next meeting was with former President Jimmy Carter at the Carter Center. There have been many similar events since that first one. And then a United Religions Initiative that uses AI was born and now has 699 centers around the world.

The first event stands out as one of the high moments of my career because it taught me that we live in worlds that our questions create.

The Moment When…

I DISCOVERED MY FUTURE

Suchitra Nelson, PhD (GRS '84, nutrition; '88, '92, epidemiology and biostatistics), is an assistant dean, and clinical and translational research professor in the Department of Community Dentistry.

Years ago, I was working to complete a master's degree in nutrition because I thought I wanted to become a dietitian. But the more training I got, the more I began to realize I wasn't interested in looking at diet and nutrition on an individual level.

As part of my coursework, I took a class in epidemiology, which looks at the way a disease is distributed in the population and uses a population approach to think about ways to prevent and treat disease and illness. It combined the ideas of medical research and public health, both of which were interesting to me. It was a way of thinking that I had never encountered before.

That class was the moment I decided to shift my focus. Now, I do work in epidemiology where our projects have been designed to reduce oral health disparities in populations, including poor, minority and special needs children and adults.

Today, for example, I'm doing research that looks at the ways pediatricians can help reduce cavities in children. We're asking pediatricians to deliver oral health facts to parents of children, and we hope that these conversations—coming from [someone parents trust and respect]—will [persuade] parents to take their child to the dentist. Since pediatricians see many children, that message will be delivered on a larger scale.

We're still in the middle of the project, but we believe this work could have a very powerful impact in improving children's oral health. I'm proud of doing work like that.

The Moment When…

I SAW A DEEP FLAW IN THE LEGAL SYSTEM

Maxwell Mehlman, JD, is a Distinguished University Professor and director of the Law-Medicine Center.

In my health-law teaching, I cover protections for people with disabilities, including the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. I portrayed the laws and regulations as thorough, powerful and effective.

But a few years ago, I began representing a family member with a disability in a dispute with an employer, which was a government agency. What I experienced was so much different than what I taught.

I watched as the employer obfuscated and delayed while my family member asked for a reasonable accommodation to do work without suffering extreme discomfort. I had been a lawyer before I became a professor, and I had been used to seeing the law do its job, which was to rectify wrongs. This was definitely a wrong.

The experience transformed my understanding of our legal system in a profound way. I had been under the impression that the law worked just fine for the wealthy but not the poor, who couldn't afford good legal help. What I realized, as a result of this experience, is that it doesn't work well for the middle class, either. In my classroom today, I'm more skeptical. I spend more time talking to students about how challenging it is to provide services to those in need.

Since then, I've also spent a lot of time thinking about how to fix the problem of providing affordable legal services to the middle class.

I'm encouraged that I'm not the only person who's trying to solve this problem.

Photographs by Michael F. McElroy