launch

Windows into War

PHOTO: ANNIE O'NEILL

PHOTO: ANNIE O'NEILLJim Sheeler

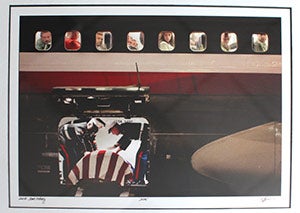

In the photo on the wall of my office, passengers in an American Airlines 757 stare through the oval windows of the airplane. Underneath them, in the cargo hold, Marines adjust the American flag atop the casket of 2nd Lt. James J. Cathey. When photographer Todd Heisler took that photo, I stood alongside him on the runway, shattered by the screams of a 23-year-old pregnant war widow seeing her husband's casket for the first time.

When Todd snapped the shutter, my current students were in third grade.

As a reporter in Colorado, I covered the effects of war from the homefront, telling stories of the families that often bore the brunt of the trauma. The journey led me to that scene on the runway that now hangs in my office—a scene that, as a professor, I strive to make tangible.

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROY

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROYAs a newspaper reporter, Jim Sheeler wrote about the war at home and what happens when--and after--families are notified of a soldier's death. The photo above, taken by photographer Todd Heisler, hangs in Sheeler's campus office and became an iconic image for the stories he told.

In one of my two classes on the power of war stories, first-year students visit the Cleveland Veterans Memorial with a blank sheet of paper, a crayon and a name. Once they find that name, each student makes a rubbing of it and spends weeks researching the life story of the person their crayon only began to reveal. Other classes meet soldiers and families. They visit the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, where they hold the prosthetics that will replace missing limbs. They learn the importance of bearing witness from journalists who have risked their lives for a story.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have been part of these students' entire lives, but often only in the background. There are windows that none of us want to look through. Courses in the humanities can show us where they are, and give us the strength to not look away.

Sheeler is the author of Final Salute, a book based on his Pulitzer Prize-winning feature story published in 2005 about fallen soldiers and the families they left behind. Todd Heisler won a Pulitzer Prize for the story's photography. Students in Sheeler's first-year seminar "Telling War Stories" last fall wrote essays reflecting on what they learned during the semester. Excerpts from four essays follow.

Studying War

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROY

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROYJake Kucia

From Strongsville, Ohio; plans to major in economics and finance.

One of his assignments was to learn more about the name on a piece of paper: James L. Blaskis.

I couldn't believe what I was holding, a name, yes, but more than that, it was a story, a life, and I was going to make sure I did his name and story justice when I wrote his obituary. ... James was killed during the Vietnam War, on the USS Forrestal in one of the biggest accidents in U.S. Navy history.

On that fateful day, James and two others were trapped in the port-side steering area by a rocket that had exploded above them on the landing strip of the large air-craft carrier. ... James, being the least injured of the men inside, began to give medical attention to his fellow crew members and stayed in communication with the central control center. ... When people think of heroes, they think: Batman, Superman and Spider-Man. However, when I think hero, I think of those who have given up their own lives for the betterment of our country.

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROY

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROYAshtar Abboud

Raised in both Greater Cleveland and Khirbet Qanafar, Lebanon; majoring in English. She saw nonstop media coverage of the terrorist attacks in Paris last November, but little on a bombing that killed 43 people in Beirut the day before.

After days of being enraged with the constant media coverage of Paris, or rather the lack of media coverage of Beirut, I came to the realization that I am just as bad as all those showing support for Paris and not Beirut. The only reason I care about what is happening in Lebanon is because, to me, that's home. I couldn't care less about what was happening in other parts of the world, like Africa or Western Asia, because I hold no connection to those places. As I sat down thinking about all of this, I came to another realization. I do care. ... This class made me care. It showed me that all lives are important, even if I don't necessarily have a direct tie to them.

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROY

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROYPratyusha Sambaru

From Hyderabad, India; majoring in math and physics. She loves storytelling and took the class because she's long been drawn to war stories.

This class has answered one question I've always pondered upon: For as long as I remember, I've been hearing stories and telling stories, but why? What makes stories so special? Before taking this class, I thought I had an answer: We tell stories to entertain ourselves. But what is so entertaining about war? Absolutely nothing. ... So why do we tell stories? It is to connect, to feel secure and to understand. Stories help us find our place in this utterly unpredictable universe. To say that you were here, you met this person, you learnt something today that makes you embrace the certainty of your past.

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROY

PHOTO: MICHAEL F. MCELROYTristan Maidment

From Villanova, Pa.; plans to major in computer engineering. The class helped him better understand the impact of war, the power of storytelling—and the limits of the written word.

While learning about writing obituaries and such, I personally found that there are some emotions that can't be expressed in the text alone. ... For instance, I have tried to stop using text messages as a form of communication; I realized that there are many nuances in the way we speak that convey as much meaning as a word itself. It has convinced me that email and instant messages are not nearly as powerful as face-to-face communication. I have noticed a very large, positive change with this new attitude. I get a better response from friends and other students, and teachers take my questions and inquiries more seriously. In addition, calling a friend instead of texting often provides a better response.