LENS Read

A Tireless Advocate

Recounting the Life of a Civil Rights Champion and Beloved Congressman

U.S. Rep. Louis Stokes always asked polite but pointed questions of the directors from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) who came before his subcommittee for budget approval. For example, what exactly were they doing to research higher rates of cancer, diabetes, hypertension and other illnesses among minorities?

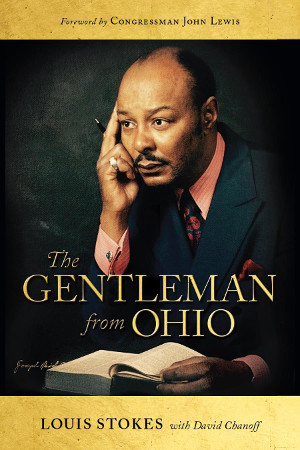

Stokes’ passion for minority health is highlighted in his autobiography, The Gentleman from Ohio, co-written with David Chanoff, a Massachusetts-based nonfiction author. The book, finished weeks before Stokes’ death in 2015 and released at Case Western Reserve last fall, recounts his rise from poverty in Cleveland to become Ohio’s first African-American congressman.

Known for leading the Congressional Black Caucus, he also chaired several key committees, including the House Select Committee on Assassinations, the Ethics Committee and the House Intelligence Committee. Stokes worked equally hard to improve health care for African-Americans.

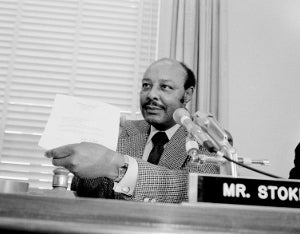

PHOTO: Associated Press / John Duricka

PHOTO: Associated Press / John DurickaCongressman Louis Stokes during a 1977 U.S. House of Representatives committee meeting.

He secured funding for Morehouse School of Medicine and other black graduate health professional schools, and worked to win passage of a 1990 law that improved access to health care and health professions for disadvantaged people, including minorities. The NIH made researching health disparities a priority in large part because of him, and named a building on its Bethesda, Maryland, campus in his honor.

Stokes wrote in the autobiography that his proudest accomplishment after 30 years in the House “was what I had done to further health care, particularly minority health care.” After retiring from Congress in 1998, Stokes taught at Case Western Reserve’s Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences and continued his advocacy for minority health care.

“He didn’t retire,” Chanoff said. “He kept working for what he believed.”

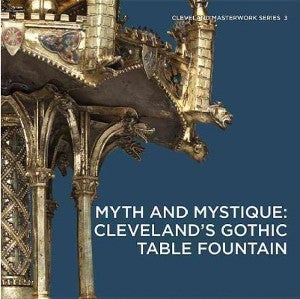

Myth and Mystique: Cleveland’s Gothic Table Fountain by Stephen N. Fliegel, curator of medieval art at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), and Elina Gertsman, PhD, professor of medieval art. CMA's ornate table fountain from the mid- 1300s is the only one of its kind to survive intact from the Middle Ages. This catalog, written for a recent exhibit at the museum centered on the fountain, delves into the history, use and artistic merit of the rare object— with its intricate, miniature parapets and arches, water wheels and nozzles in the shapes of dragons. The catalog also examines the fountain in the context of other luxury objects and includes entries by CWRU graduate students.

The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History, edited by Duquesne University President Ken Gormley, JD, with a chapter by Jonathan Entin, JD, Case Western Reserve’s David L. Brennan Professor Emeritus of Law. Historians and legal experts collaborated to examine historical turning points and presidential decisions that impacted and shaped interpretations of the U.S. Constitution. Entin wrote the chapter on President John Quincy Adams.

Forging the Future of Special Collections, co-edited by Melissa Hubbard, the Kelvin Smith Library head of special collections and archives, Arnold Hirshon, associate provost and university librarian, and Robert H. Jackson, JD (LAW ’61), a partner at the Kohrman Jackson & Krantz law firm who is serving as a Kelvin Smith Library Distinguished Visiting Scholar. Based on the library’s 2014 National Colloquium on Special Collections, this collaboration of librarians, university faculty and donors highlights the evolution of special collections in the 21st-century information age. It also explores ways to build special collections that are digitized and accessible across the globe and it showcases examples of applying digital scholarship techniques to these collections.

Women Writers of Gabon: Literature and Herstory by Cheryl Toman, PhD, associate professor of French and director of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program and the Ethnic Studies Program. Toman explores the rich, unique and little-known writings of the women of Gabon—and why these works have not received widespread recognition. She describes the depth and range of the women’s literary contributions and argues that their work should be considered a major force in the African literary canon.