Former university employee and 1994 graduate won an Oscar for innovations in facial animation—his hobby-turned-career

Geoff Wedig made Brad Pitt look old and Jeff Bridges look young. And now he has an Academy Award to show for it. The Case Western Reserve alum is the first to admit it’s an unlikely path for a math and English double-major. In fact, it wasn’t until his mid-30s that Wedig—who is 44 now—decided he wanted to work in the film industry. Geoff and Kathy Wedig at the Feb. 11 Oscars ceremony in Beverly Hills

Accepting his award at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel on Feb. 11, he credited his wife—Kathy Wedig (née Kovacic), who holds a PhD in computer engineering from CWRU—for her role in his achievement.

“When I told her I wanted to change professions, she didn’t say no; she didn’t even look appalled,” he said. “For that, I’ll be eternally grateful.”

The Oscar—an award for technical achievement that he shared with fellow software engineer Nicholas Apostoloff—recognizes the impact made by software they co-wrote that animates faces.

“Human beings are biologically attuned to notice faces. We do it just weeks after we’re born and are hard-wired to notice if something isn’t quite right,” Wedig said. “It can ruin a scene or a film, so the stakes are high.”

Wedig’s film credits include the blockbusters Maleficent, TRON: Legacy, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Night at the Museum 3.

His software was also responsible for one of the most talked-about pop culture moments of 2012, when a hologram of deceased rapper Tupac Shakur performed songs at a music festival in California.

Geoff and Kathy Wedig at the Feb. 11 Oscars ceremony in Beverly Hills

Accepting his award at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel on Feb. 11, he credited his wife—Kathy Wedig (née Kovacic), who holds a PhD in computer engineering from CWRU—for her role in his achievement.

“When I told her I wanted to change professions, she didn’t say no; she didn’t even look appalled,” he said. “For that, I’ll be eternally grateful.”

The Oscar—an award for technical achievement that he shared with fellow software engineer Nicholas Apostoloff—recognizes the impact made by software they co-wrote that animates faces.

“Human beings are biologically attuned to notice faces. We do it just weeks after we’re born and are hard-wired to notice if something isn’t quite right,” Wedig said. “It can ruin a scene or a film, so the stakes are high.”

Wedig’s film credits include the blockbusters Maleficent, TRON: Legacy, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Night at the Museum 3.

His software was also responsible for one of the most talked-about pop culture moments of 2012, when a hologram of deceased rapper Tupac Shakur performed songs at a music festival in California.

Starting Over

Wedig's work in Hollywood is a far cry from his job at Case Western Reserve, where he spent 12 years writing computer code to identify genes linked to diseases for the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatics in the School of Medicine. “Around the early 2000s I wanted to do something else,” said Wedig, who lives in Los Angeles with Kathy and their three children. So he returned to his roots. Since Wedig was 10 years old, the Marietta, Ohio, native had experimented with computer graphic imagery (CGI). Using an educational license (thanks to his CWRU job), Wedig bought a $40,000 visual effects program for a just few hundred dollars. On evenings and weekends, he taught himself animation. The result was a trailer for a non-existent movie—Invasion from Beyond the Galaxy!—in the vein of low-budget sci-fi films from the 1950s. “I worked on it every minute I could, and it still took me 18 months to make something 90 seconds long,” he said. “The process helped me try everything, but people thought I was nuts.” With the trailer as his resume, Wedig parlayed the work into a position at Digital Domain—a studio founded by James Cameron—in southern California. Within a year, he was writing code to help animate Pitt’s hair, as the actor played a man aging in reverse. “You want to make sure hair looks random, but random in the right way,” Wedig said. In TRON: Legacy, Jeff Bridges appeared younger in flashback scenes--thanks to software written by Wedig and Apostaloff. / Promotional photo courtesy of Disney Enterprises, Inc.

A year later, he was making the 60-something Bridges appear to be in his 30s in TRON: Legacy. Along the way, Wedig co-authored the software that won him the Oscar.

His timing could not have been better: Demand for lifelike facial animation only continues to grow—not only to tinker with character traits but to also recreate actors onscreen who are unavailable due to injury or death.

In TRON: Legacy, Jeff Bridges appeared younger in flashback scenes--thanks to software written by Wedig and Apostaloff. / Promotional photo courtesy of Disney Enterprises, Inc.

A year later, he was making the 60-something Bridges appear to be in his 30s in TRON: Legacy. Along the way, Wedig co-authored the software that won him the Oscar.

His timing could not have been better: Demand for lifelike facial animation only continues to grow—not only to tinker with character traits but to also recreate actors onscreen who are unavailable due to injury or death.

The Uncanny Valley

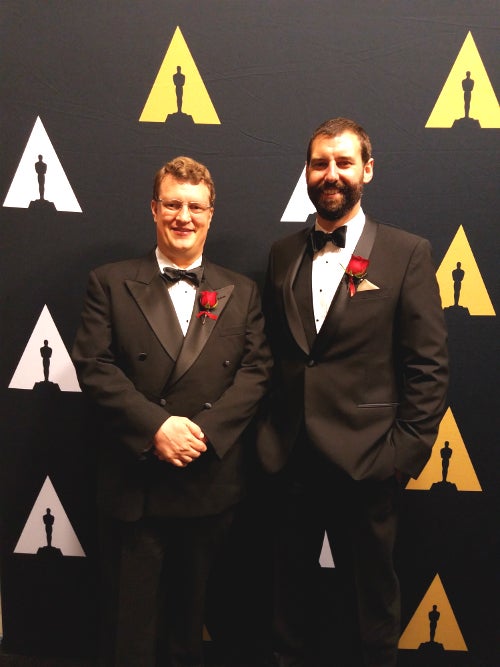

Improvements in animation do not automatically make Wedig's job easier—thanks to human psychology. There’s a paradox in facial animation encapsulated by a concept known as the uncanny valley, where the more realistic a human character appears, the more risk there is in alarming an audience. Characters who are obviously on one side of the valley—think Charlie Brown—are fine, but if animated humans look close to real, but not entirely lifelike, there is a sharp dip in appeal. Wedig and Apostoloff at the Feb. 11 Oscars ceremony

“They look like mannequins given life, which can creep people out,” said Wedig. “But once you reach the other side of the valley, people respond to characters as real people.”

“Getting across uncanny valley is the holy grail of what I do,” he added.

His software continues to evolve and was used heavily in Deadpool and the upcoming remake of Beauty and the Beast. To Wedig, this success is the sweetest retort to the armchair quarterbacking of online trolls who nitpick the visual effects of Hollywood films.

“It’s thrilling that we are always getting closer to blurring the line between animation and reality,” said Wedig, who now works at Magic Leap Inc. “We are going to crack it.”

The televised Oscars ceremony, which will include a segment about Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Technical Achievement awards, will air live on ABC on Sunday, Feb. 26.

Wedig and Apostoloff at the Feb. 11 Oscars ceremony

“They look like mannequins given life, which can creep people out,” said Wedig. “But once you reach the other side of the valley, people respond to characters as real people.”

“Getting across uncanny valley is the holy grail of what I do,” he added.

His software continues to evolve and was used heavily in Deadpool and the upcoming remake of Beauty and the Beast. To Wedig, this success is the sweetest retort to the armchair quarterbacking of online trolls who nitpick the visual effects of Hollywood films.

“It’s thrilling that we are always getting closer to blurring the line between animation and reality,” said Wedig, who now works at Magic Leap Inc. “We are going to crack it.”

The televised Oscars ceremony, which will include a segment about Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Technical Achievement awards, will air live on ABC on Sunday, Feb. 26.