Cleveland’s famous sea monster gets a scientific update

New research reveals Dunkleosteus was an oddball among ancient armored fishes

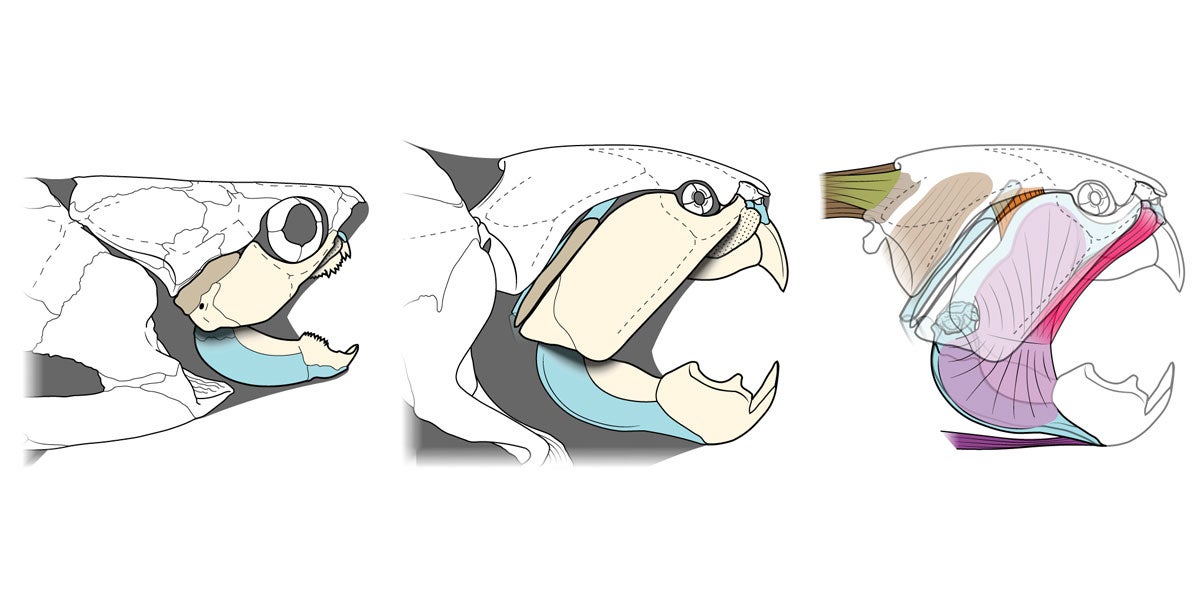

About 360 million years ago, the shallow sea above present-day Cleveland was home to a fearsome apex predator: Dunkleosteus terrelli. This 14-foot armored fish ruled the Late Devonian seas with razor-sharp bone blades instead of teeth, making it among the largest and most ferocious arthrodires—an extinct group of shark-like fishes covered in bony armor across their head and torso.

Since its discovery in the 1860s, Dunkleosteus has captivated scientists and the public alike, becoming one of the most recognizable prehistoric animals. Casts of its bony-plated skull and imposing mouthparts can be seen on display in museums around the world. Despite its fame, this ancient predator has remained scientifically neglected for nearly a century.

Now an international team of researchers led by Case Western Reserve University has published a detailed study of Dunkleosteus in The Anatomical Record, revealing a new understanding of the ancient armored predator.

Despite being the literal “poster child” for the arthrodire group,

Dunkleosteus actually was not like most of its kin, and was in fact, a bit of an oddball.

Filling a 90-year knowledge gap

“The last major work examining the jaw anatomy of Dunkleosteus in detail was published in 1932, when arthrodire anatomy was still poorly understood,” said Russell Engelman, a graduate student in biology at Case Western Reserve and lead author. “Most of the work at that time focused on just figuring out how the bones fit back together."

Arthrodire fossils can be difficult to work with. Their remains are often crushed and flattened and had bodies mostly made of cartilage; only their bony head and torso armor are regularly preserved.

“Since the 1930s, there have been significant advances in our understanding of arthrodire anatomy, particularly from well-preserved fossils from Australia,” Engelman said. “More recent studies have tried biomechanical modeling of Dunkleosteus, but no one has really gone back and looked at what the bones themselves say about muscle attachments and function.”

The team, including researchers from Australia, Russia, the United Kingdom and Cleveland, has brought Dunkleosteus into the modern era of paleontology by analyzing specimens from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History—home to the world's largest and best-preserved collection of Dunkleosteus fossils.

Dunkleosteus likely lived around the world during the Devonian period, but conditions in Cleveland allowed for a bonanza of skeletal remains to be preserved in the ancient seafloor, now a layer of black shale rock exposed by area rivers and road construction projects.

Surprising discoveries

The researchers’ detailed anatomical analysis revealed several unexpected findings:

- A cartilage-heavy skull: Nearly half of Dunkleosteus’ skull was composed of cartilage, including most major jaw connections and muscle attachment sites—far more than previously assumed.

- Shark-like jaw muscles: The team identified a large bony channel housing a facial jaw muscle similar to those in modern sharks and rays, providing some of the best evidence for this feature in ancient fishes.

- An evolutionary oddball: Despite being the poster child for arthrodires, Dunkleosteus was unusual among its relatives. Most arthrodires had actual teeth, which Dunkleosteus and its close relatives lost in favor of their iconic bone blades.

Rewriting arthrodire evolution

Perhaps most importantly, the study places Dunkleosteus in proper evolutionary context. The bone-blade specializations of Dunkleosteus and its relatives reflect increasing adaptation for hunting other large fishes—features that evolved independently in other arthrodire groups as well. The blades allowed these predators to bite chunks out of large prey, Engelman explained.

“These discoveries highlight that arthrodires cannot be thought of as primitive, homogenous animals, but instead a highly diverse group of fishes that flourished and occupied many different ecological roles during their history,” Engelman said.

The findings transform our understanding of both Dunkleosteus specifically and arthrodire diversity more broadly, showing that even the most famous fossils can still yield new insights.