When computers took over the factory floor: Case Western Reserve economist traces how workers adapted—and what it means for AI's future

In the early 1970s, a quiet revolution began in American factories. Lathes, drill presses and milling machines—once guided by the steady hands of skilled machinists—started thinking for themselves.

Computer numerical control (CNC) technology, as it was called, transformed these tools into automated systems that could execute complex operations from programmed instructions—with no human touch required.

Sound familiar?

As artificial intelligence (AI) stands to automate white-collar work on an unprecedented scale, a new study co-authored by Case Western Reserve University economist David Clingingsmith examines what happened another time computers came for American jobs—and what it can teach us today.

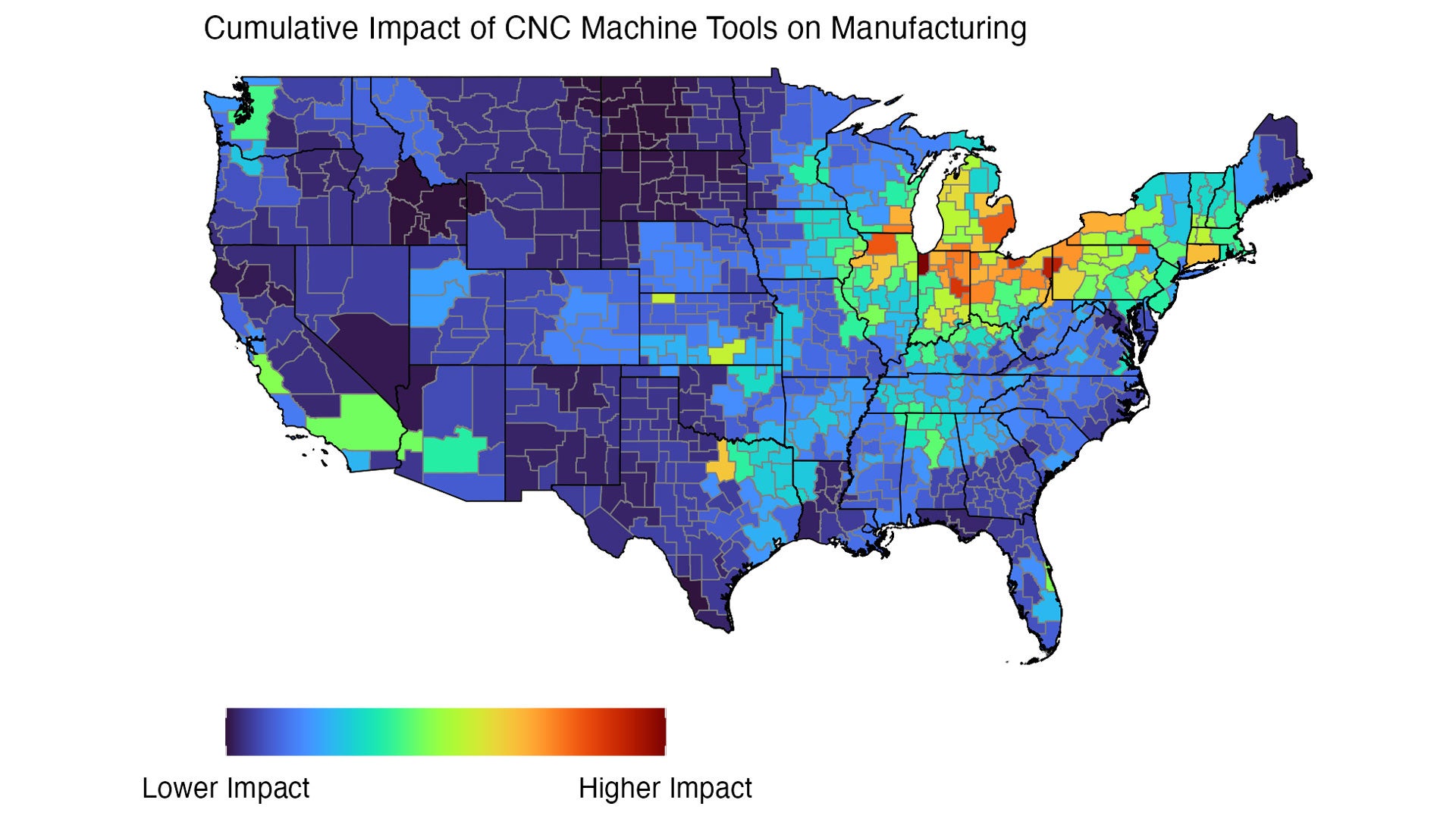

The research, conducted with researchers from Yale and Brandeis universities and published in the Review of Economics and Statistics, meticulously traces how computerized machine tools reshaped manufacturing from 1970 to 2010. The team built a detailed measure of which industries and regions were hit hardest, then tracked long-term impacts on productivity, jobs and workers.

“This is the missing chapter in America’s automation story—the bridge between factory electrification and today’s robots and AI,” said Clingingsmith, associate professor of economics at Weatherhead School of Management. “What surprised us was how well workers adapted. They didn’t just lose jobs and disappear. They fought back.”

That fight took several forms.

Clingingsmith said workers left metal manufacturing for plastics or wood products—industries computers couldn’t yet master—or moved into wholesale and retail trade. Union protection made a crucial difference: In the 1970s, 45% of metalworkers belonged to unions that could negotiate job protections and retraining programs. Others returned to school, as colleges quickly added degrees in computer-aided manufacturing and engineering.

The result? Unlike the robot revolution of recent decades, CNC automation boosted productivity without triggering net job losses in affected areas.

“Those transitions weren’t painless,” Clingingsmith cautioned. “When you lose a good job and your role falls out of an industry, you can end up on a lower trajectory—even if you adapt.”

Key findings from the study include:

- Productivity and jobs: CNC technology boosted labor productivity by 7% but reduced production employment by 12%, with job losses concentrated among non-union, mid-skilled workers with a high school education or less.

- Skills shifts: Employment declined 24% for high school dropouts but increased 17% for college graduates, reflecting automation's displacement of routine tasks and creation of new demand for programming skills.

- Adaptation: Displaced workers successfully shifted to non-metal manufacturing and retail sectors, while enrollment in CNC-related college programs surged as workers retrained for higher-skilled positions.

Clingingsmith said the findings shed light on today’s AI debate. CNC technology mainly affected middle-income workers, such as machinists and autoworkers. AI, by contrast, could “come for the jobs” of highly educated professionals in law and finance and others in customer service positions.

“The workforce adapted to computers in the 1970s, but the conditions that made that possible—strong unions, concentrated industry impacts and available alternatives—may not exist for the AI transition,” Clingingsmith said. “We can’t insulate workers from technological change, but we can help them adjust. That means recognizing how education needs will shift and ensuring people have paths to retraining.”

The regions hardest hit by CNC automation—the Rust Belt and what Clingingsmith calls the “aircraft manufacturing archipelago” of Southern California and suburban Seattle—offer another lesson.

“Clusters still matter,” he said. “The same places that once lost factory jobs could become growth engines again for high-value manufacturing if we invest in the skills and systems to support them.”

Weatherhead School of Management, economics, Homepage News, release, Business, Law + Politics