Funeral services will be held Saturday, March 19, for Patricia Baldwin Kilpatrick, a beloved member of the Case Western Reserve community for more than 50 years and the university’s first female vice president. Pat, as she was known, died peacefully Thursday, March 3, with her daughter Kate by her side. She was 88.

“Case Western Reserve has lost one of its most extraordinary leaders,” President Barbara R. Snyder said. “An exceptional educator, administrator and alumna advocate, Pat brought insight and energy to all that she did. Her impact on students and colleagues cannot be overstated, and she will be deeply missed.”

Pat was born in 1927 in Cleveland, and graduated from East Cleveland’s Shaw High School. She initially attended Ohio Wesleyan University, where she became a member of Kappa Alpha Theta. In 1947, she transferred to Flora Stone Mather College for Women in 1947 for family reasons, and quickly grew to love the campus community. She competed in basketball, volleyball, field hockey and riding for Mather, and graduated in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree in history.

Pat had hoped to attend the university’s law school after graduation and even won admission, but ultimately had to turn down the acceptance because she could not afford to enroll. Still, the department chair for physical education insisted Pat needed some kind of advanced degree, and so arranged for her to pursue a master’s degree while living in Haydn Hall. After graduation in 1951, she married, had three children and taught at the high school level.

Funeral services will be held Saturday, March 19, for Patricia Baldwin Kilpatrick, a beloved member of the Case Western Reserve community for more than 50 years and the university’s first female vice president. Pat, as she was known, died peacefully Thursday, March 3, with her daughter Kate by her side. She was 88.

“Case Western Reserve has lost one of its most extraordinary leaders,” President Barbara R. Snyder said. “An exceptional educator, administrator and alumna advocate, Pat brought insight and energy to all that she did. Her impact on students and colleagues cannot be overstated, and she will be deeply missed.”

Pat was born in 1927 in Cleveland, and graduated from East Cleveland’s Shaw High School. She initially attended Ohio Wesleyan University, where she became a member of Kappa Alpha Theta. In 1947, she transferred to Flora Stone Mather College for Women in 1947 for family reasons, and quickly grew to love the campus community. She competed in basketball, volleyball, field hockey and riding for Mather, and graduated in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree in history.

Pat had hoped to attend the university’s law school after graduation and even won admission, but ultimately had to turn down the acceptance because she could not afford to enroll. Still, the department chair for physical education insisted Pat needed some kind of advanced degree, and so arranged for her to pursue a master’s degree while living in Haydn Hall. After graduation in 1951, she married, had three children and taught at the high school level.

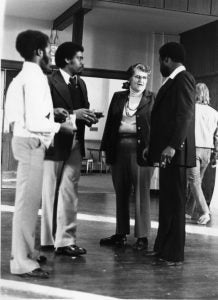

She returned to Case Western Reserve in 1962, spending three years as a faculty member in physical education, then becoming a dean at Mather College. It was in this latter role that she met a first-year student named Stephanie Tubbs Jones, who would go on to become a member of the U.S. Congress before dying of a brain aneurysm in 2008. Speaking at President Snyder’s investiture ceremony the previous year, Rep. Tubbs Jones singled out two people in the audience: her congressional predecessor and mentor Louis Stokes, and Pat.

“I loved her so much I had [my son] Mervyn on her birthday,” Tubbs Jones said, then later spoke of how important it was for young women to see females in leadership positions. “Once they see a positive example of what they can become, their possibilities for the future are limitless.”

Tubbs Jones and thousands of others had such a role model in Kilpatrick. The dean did not hesitate to discipline students who violated rules, but at the same time made clear she did so because she saw something more within them. She also showed great compassion to students devastated after bad grades or poor test scores; from experience, she knew well how they felt.

“When I first came to college, I was thinking of becoming a doctor, but that changed because I failed organic chemistry,” Kilpatrick said during a 2010 interview. “Failing a course was the best thing that could have happened to me because when I was a dean and talking to kids who had failed courses and thought their life was over, I said, ‘Well, it isn’t.’

“Then I’d tell them that I failed a course... Then they’d think, ‘Well, maybe it isn’t the worst thing,’ [and] I said, ‘You have to come back and put your mind to what you’re going to take next.’”

She returned to Case Western Reserve in 1962, spending three years as a faculty member in physical education, then becoming a dean at Mather College. It was in this latter role that she met a first-year student named Stephanie Tubbs Jones, who would go on to become a member of the U.S. Congress before dying of a brain aneurysm in 2008. Speaking at President Snyder’s investiture ceremony the previous year, Rep. Tubbs Jones singled out two people in the audience: her congressional predecessor and mentor Louis Stokes, and Pat.

“I loved her so much I had [my son] Mervyn on her birthday,” Tubbs Jones said, then later spoke of how important it was for young women to see females in leadership positions. “Once they see a positive example of what they can become, their possibilities for the future are limitless.”

Tubbs Jones and thousands of others had such a role model in Kilpatrick. The dean did not hesitate to discipline students who violated rules, but at the same time made clear she did so because she saw something more within them. She also showed great compassion to students devastated after bad grades or poor test scores; from experience, she knew well how they felt.

“When I first came to college, I was thinking of becoming a doctor, but that changed because I failed organic chemistry,” Kilpatrick said during a 2010 interview. “Failing a course was the best thing that could have happened to me because when I was a dean and talking to kids who had failed courses and thought their life was over, I said, ‘Well, it isn’t.’

“Then I’d tell them that I failed a course... Then they’d think, ‘Well, maybe it isn’t the worst thing,’ [and] I said, ‘You have to come back and put your mind to what you’re going to take next.’”