CWRU researcher leads NASA experiment on ISS to advance long-duration spaceflight

For deep-space missions to the moon, Mars and beyond, one deceptively simple question drives some of NASA’s most complex engineering challenges: How do you keep enough fuel cold—and stable—long enough to use it?

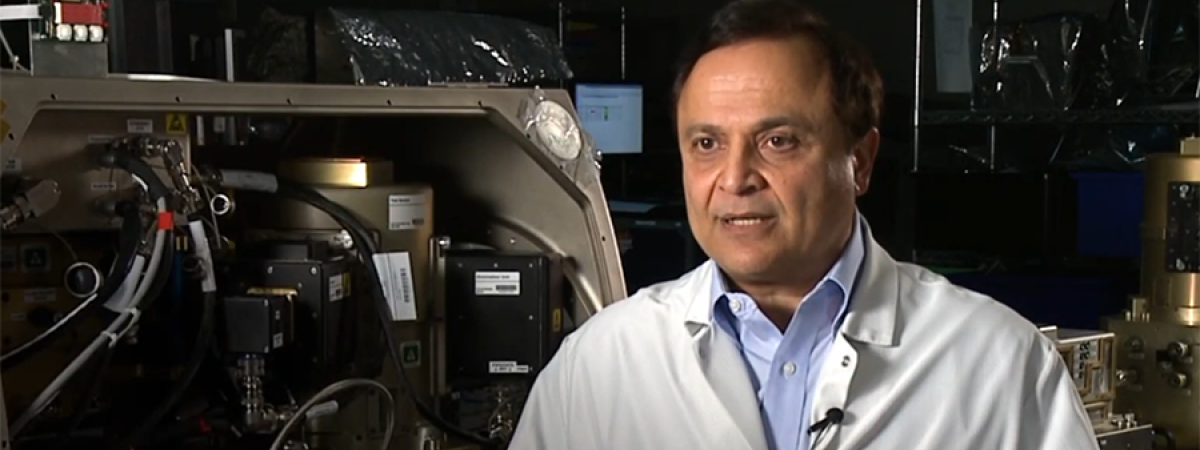

That problem is at the center of ongoing zero boil-off tank (ZBOT) research, which includes a series of NASA-sponsored microgravity experiments led by Mohammad Kassemi, PhD, research professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Case Western Reserve University. The latest ZBOT mission launched in October and is collecting data aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

“To put it in simple terms, if you want to go on a road trip, the first thing you do is make sure you have gas in your tank and places to fuel up along the way,” Kassemi said. “NASA has the exact same problem, except there are no gas stations orbiting in microgravity.”

The “gas” in this case is cryogenic fuel—liquid hydrogen, oxygen and methane—kept at extremely cold temperatures. Hydrogen, for instance, must stay near 20 Kelvin; any heat that enters a storage tank causes the liquid to evaporate, raising pressure. Today, spacecraft protect tank integrity by venting that vapor into space, but that means losing fuel.

For long-duration missions, that loss is enormous.

“If you want to go to Mars, you need about 38 tons of fuel,” Kassemi explained. “But you lose 18 tons per year to boil-off if you use a venting system. By the time you travel back, you could be out of fuel—or you’d have to carry an extra 38 tons. That means huge costs and safety risks.”

Zero-boil-off strategies offer a solution: Actively mix and cool the tank fluid to prevent fuel from evaporating. But in microgravity, liquids and vapors don’t behave the same way they do on Earth. “In space, the interface between liquid and vapor doesn’t stay flat—it becomes a spherical shape,” Kassemi said. “As you mix and cool, the jet you use interacts with that interface in different ways. All of those dynamics have to be understood to design a system that works.”

That’s what the ZBOT experiments accomplish. The first mission in 2017, ZBOT-1, examined how tanks pressurize and how mixing and cooling can reduce pressure. Like the current mission, it used a small-scale tank filled with simulant fluids rather than true cryogens, capturing microgravity data to validate the models used to design full-scale systems.

The current mission, ZBOT-NC, repeats those earlier tests but adds a key complication: non-condensable gases. In real spacecraft, tanks are often pressurized with helium for fuel transfer—and that helium remains, affecting evaporation and condensation. “We expect it might slow down condensation, making it harder to control tank pressure,” Kassemi said. “That’s the complication we’re studying.”

The experiment is operating in the ISS Microgravity Science Glovebox, run by NASA and the ZBOT-NC engineering team at Sierra Lobo Inc, with data downlinked to Earth for Kassemi and his team in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering: Assistant Research Professor Olga Kartuzova, EngD, Senior Research Engineers Sonya Hylton and Rebecca Winter Schreiber, PhD, CWRU undergraduate and NASA research intern Osi Chukwuocha, and collaborators at NASA Glenn Research Center and Sierra Lobo Inc. Over the next several months, the team expects to gather thermal images and sensor measurements that will validate models critical for future large-scale cryogenic storage demonstrations.

“The hope is that we can eventually establish a depot system in orbit,” Kassemi said. “In the future, we’re hoping to do a large demonstration in space with real cryogens to validate the technology, but you need data and models to troubleshoot potential problems—and that’s what these ZBOT experiments will provide.”