Rethinking the Middle Ages: CWRU art historian reframes abstraction

When you consider abstract art, your mind likely conjures images of works by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Piet Mondrian: bold shapes, swaths of vibrant colors and innovative techniques.

However, an international team of art historians is challenging that perception with their research on abstraction in the Middle Ages. Backed by a French-American Cultural Exchange Foundation grant, the project was launched by Elina Gertsman, Distinguished University Professor and the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Case Western Reserve University, and Vincent Debiais, research professor at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris.

Their multipronged research project, Abstraction Before the Age of Abstract Art, included a public-facing blog leveraging graduate student contributions, several workshops and symposia, and a recently published book: L’hypothèse abstraite – Écart, excès d’image au Moyen Âge (les presses du réel 2025).

“It challenges the entire way that we're looking at medieval art,” Gertsman said. “I really think it's a game changer.”

Representing the unrepresentable

Gertsman’s inquiries into unusual and striking images have earned her acclaim as a medievalist. She has published on the macabre Dance of Death murals, opening sculptures of the Virgin Mary, erasure in manuscripts, as well as emotion, cognition, performance, memory, and the senses in medieval art. Her research primarily focuses on the 12th through 15th centuries, and ranges from Scandinavia to Italy.

Gertsman’s exploration of emptiness and absence in art—or the divorce between what is known and what is seen—was the preamble to her work on abstraction. Her collaborator, Debiais, encountered the topic as he dug into silence visualized in art.

Together, they came to challenge the notion that abstraction was invented in the 20th century—and along with their students, they engaged in a multi-year, philosophically charged exercise that forced them to reconsider the very basics of what they knew. What is an image? What does it mean to paint or sculpt the unknowable?

Working at numerous sites, museum collections, and libraries across Europe and the U.S., the research team arrived at a driving question: How do you represent the unrepresentable? They found medieval artists conveyed complex ideas through their works using abstraction.

“We began seeing abstraction as the impetus for figuration, not its opposite,” Gertsman said. “What lies beyond the senses? How do you access knowledge? How do you paint something that just trips up every operation of cognition and every operation of perception?”

Through their research, the team found depth in the interrelationship between art and philosophy, particularly nuanced in the Middle Ages.

“In fact, it was a time of a lot of complex thinking, both about art and what it can do, but also about how to work through ideas, both textually and visually,” said Reed O’Mara, a Mellon Foundation Fellow and PhD candidate in the Department of Art History and Art who contributed to the body of work.

An ever-evolving vision

Traveling to a planned symposium in Paris over this past summer, Gertsman checked her email during a layover to find exciting news: their book had just been published, months ahead of schedule.

She wanted to get her hands on a copy before her first talk two days later. Sending off a flurry of emails, she arranged for a fresh copy to be delivered by courier. It arrived at the symposium venue less than two hours before her talk, giving her and Debiais the chance to unwrap it together and show it off during the event.

The book punctuated a series of collaborative experiences held over six years—and through a pandemic. During the collaboration, Debiais gave a keynote address at the Department of Art History and Art’s flagship graduate-run event, the Cleveland Symposium, and in the following years Gertsman served as an invited professor at the EHESS. The two co-authored an article for Convivium,“Au-delà des sens, l’abstraction,” where they tested their theories for the first time. More collaborations followed: Debiais contributed an article on color and abstraction to Gertsman’s edited volume, Abstraction in Medieval Art: Beyond the Ornament (with new paperback edition due out this December); and Gertsman was featured in “Narration / Abstraction,” a conversation between specialists in medieval and contemporary art led by Debiais, that was published in Perspective: actualité en histoire de l’art.

“It took on a life of its own,” Gertsman said, explaining the project’s transformation.

The project in numbers

At the start of this transatlantic exchange of ideas amongst colleagues, Gertsman believed the project would primarily focus on Christian manuscript illumination. But, as the team’s interests expanded, they considered more works, turning to Jewish art and engaging with a variety of different media: metalwork, sculptures, and panel paintings.

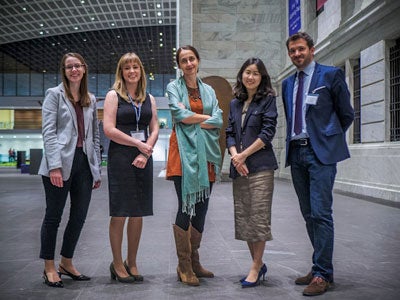

To gather insights from other art historians, Gertsman and Debiais hosted symposia and workshops at Case Western Reserve, at The National Institute for Art History in Paris, at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and at Princeton University. Debiais’s graduate students traveled to Cleveland and Gertsman’s flew to Paris to participate in these events. The grant Gertsman and Debiais received was supported by the Paccar Foundation, the Florence Gould Foundation, the Franco-American Fulbright Commission, and the French Ministries of Foreign Affairs and International Development, and of National Education, Higher Education and Research.

For O’Mara, the project encapsulates her graduate school experience. She began her Master of Arts program just as it was taking form, and she has seen it through its many iterations, giving her valuable insights into the world of publishing, collaboration and international exchange.

“Personally, I will never forget that the first time that I got to see Saint-Denis, or the Sainte-Chapelle—among the most famous monuments of medieval Gothic art in France—I got to see them with my advisor and that is the most special thing ever,” said O’Mara.

Take a look at the pieces graduate students explored throughout the project.