discover

OUT OF THE PARK DISCOVERIES

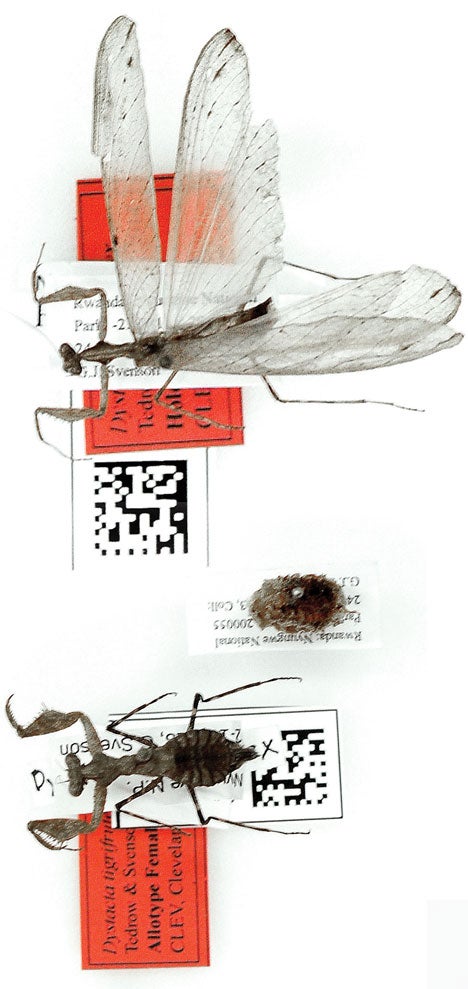

On a damp summer night in a Rwandan national park in 2013, Case Western Reserve student Riley Tedrow nabbed two praying mantises. Uncertain of their species, he reviewed hundreds of descriptions, compared his pair with vast collections of specimens and consulted his mentor. Only then did Tedrow, now a senior, feel confident that his finds were new to science. "That moment was exhilarating," he said.

Russell Engelman experienced a similar thrill in the spring of 2012. A first-year Case Western Reserve student at the time, Engelman was examining a partial skull on loan from the University of Florida. Researchers had suspected the skull—discovered decades ago—belonged to a particular group of extinct opossums. But when a skeptical Engelman compared the 13 million-year-old fossil from Bolivia with other skulls and reviewed scholarly papers, he found no match. Clue by clue, he and his mentor realized it came from an extinct, and until then unknown, ferret-sized cat-like predator.

13 million-year-old fossilized skull

13 million-year-old fossilized skull

Tedrow and Engelman—both biology majors—not only discovered the two species but also became the lead authors of the papers published this year that described them. Their finds provide new insight into two animal orders and their evolution.

Undergraduates rarely discover species large enough to be seen without a microscope, said Elizabeth Ambos, executive officer of the Council on Undergraduate Research in Washington, whose members, including CWRU, promote undergraduate research.

"Both discoveries are absolute home runs," Ambos said. "They're a testament to the students and the mentorship offered at Case Western Reserve."

What set both students on a path of discovery were two key ingredients: their longtime interests in animal life and a meeting with a professor each had while still in high school.

A chance conversation with Michael Benard, PhD, the George B. Mayer Assistant Professor of Urban and Environmental Studies and an assistant professor of biology, during a campus session for recently accepted students piqued Tedrow's interest in studying animals and renewed a fascination that began with his childhood collections of snakes and bugs.

Once on campus, he began studying with Gavin Svenson, PhD, who is now his mentor. Svenson is the Cleveland Museum of Natural History's curator of invertebrate zoology and an adjunct assistant professor of biology at CWRU.

Dystacta tigrifrutex male (top) female (bottom)

Dystacta tigrifrutex male (top) female (bottom)

The two named the new find Dystacta tigrifrutex—bush tiger mantis—for the female's hunting style.

For his part, Engelman was so enamored with prehistoric animals that he built a fossil museum while in elementary school. During the winter of his senior year in high school he attended a talk by Darin Croft, PhD, an associate professor of anatomy in the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. They spoke afterward, and almost immediately, Engelman began studying with Croft, who often works with undergraduates interested in paleontology. He decided to come to Case Western Reserve for the opportunity to work with Croft.

Analyzing the Bolivian skull was Engelman's first independent project under Croft's direction.

Once the two realized what they had, they put off naming the predator until they could find more fossils of the species and learn more about its traits.

Engelman was pleased to see his work published. But when Croft said it was worthy of a master's thesis, Engelman voiced a thought that had dogged him for months: "I should have waited." —KEVIN MAYHOOD