lens

Combating Cancer

Campus experts highlight promising advances in diagnoses and treatments

IMAGE: Sarayut/iStock/Getty Images Plus

IMAGE: Sarayut/iStock/Getty Images PlusIn a scenario evocative of history's greatest military conquests, millions of white blood cells lay siege to ravaging cancer cells, using the body's immune system to triumph over such deadly foes as melanoma skin cancer and lung cancer.

It's one advance bringing new hope for cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Research and, finally, breakthroughs "allow us to change the way the immune system responds to cancer so that it destroys advanced cancer and even immunizes patients to their own tumors," said Stanton Gerson, MD, a Distinguished University Professor and director of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (Case CCC). "For the first time, patients with devastating tumors are living for years, not months."

Such advances are among the reasons cancer deaths in the United States fell 27% from 1991 to 2016, according to the American Cancer Society.

Still, the numbers remain sobering: More than 1.76 million cases of cancer are expected to be diagnosed nationally this year, and more than 606,000 people are expected to die from the disease.

But there is reason for optimism, as research and innovations continue apace.

Two scientists won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2018 for separately discovering a revolutionary approach to cancer treatment. Using complementary strategies, they developed "immune checkpoint blockades" to ensure that only cancer cells, not healthy cells, are attacked.

And by analyzing an ever-expanding trove of electronic health data, researchers and physicians are gaining insight into clinical experiences to identify high-risk individuals who might respond to a particular treatment or be eligible for a novel medicine.

Think magazine asked cancer experts on campus to describe advances they believe are among the most promising.*

Anant Madabhushi

Anant Madabhushi

Anant Madabhushi, PhD, is the F. Alex Nason Professor II of Biomedical Engineering, a member of Case CCC, and founding director of the university's Center for Computational Imaging and Personalized Diagnostics. His specialty: artificial intelligence (AI) and imaging.

"A lot of the focus on imaging has been on the early detection and diagnosis of disease. We know if you're able to identify the disease early, that can help with an intervention that prevents the tumor from growing and therefore maximizes the likelihood of a favorable prognosis.

"But emerging is an opportunity to use computational and AI approaches to harness and extract measurements and patterns that hitherto could not be captured by visual assessment of the data alone for predicting disease outcome and how patients will respond to therapies.

"For instance, when a radiologist looks at a CT scan, she may be—based off the shape of the lesion or the specularity [visual appearance] of the margin of the lesion—trying to identify the presence or absence of cancer.

"But with a computational interrogation of the scans, we can start to pry out in a quantitative, reproducible way much more subtle patterns both inside and outside the tumor. For instance, using computational approaches, we have identified that the degree of twistedness of blood vessels associated with a lung nodule on a CT scan are different for malignant and benign lesions.

"Using artificial intelligence with routine imaging can also help determine the risk and aggressiveness of a particular cancer. And that, in turn, helps address the question of: Is somebody going to respond to chemo or immunotherapy? You want to spare the patient the toxicity of a therapy that's not going to work."

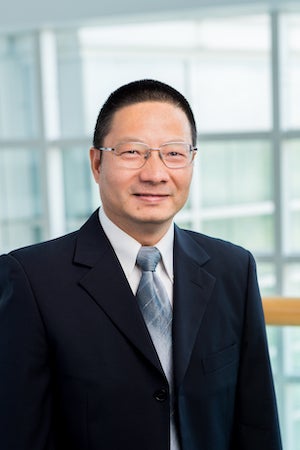

Zhenghe (John) Wang

Zhenghe (John) Wang

Zhenghe (John) Wang, PhD, the Dale H. Cowan M.D. – Ruth Goodman Blum Professor of Cancer Research, vice chair for faculty development in the Department of Genetics and Genome Sciences at the School of Medicine, and co-leader of the GI cancer genetics program at Case CCC. His specialty: genomic-based therapies.

"There have been several major breakthroughs in the last decade in cancer genomics. We've been able to sequence patient genomes [a complete set of DNA], and we are utilizing genomic information for patient treatment.

"Two really exciting treatments—targeted therapy and immunotherapy—are among the biggest breakthroughs in the last 30 years of cancer research.

"Targeted therapies attack cancer-specific molecules that do not exist in normal tissues, such as oncogenic mutations [which cause development of tumors], whereas traditional chemotherapies kill both tumor cells and normal growing cells. Thus, targeted therapies are more effective but less toxic.

PHOTO: Red_Moon_Rise/E+/Getty Images

PHOTO: Red_Moon_Rise/E+/Getty Images"We can now just draw some blood from patients to diagnose a tumor by detecting tumor-specific mutations, which is called liquid biopsy. Liquid biopsy can also be a way to monitor the patient's tumor progression.

"We're also now able to develop drugs that target oncogenic proteins in mutations. Because patients with different mutations respond to different drugs, those mutations can guide patient treatment. For example, lung cancer patients with what's known as ‘EGFR' mutations respond to Erlotinib, whereas melanoma patients with BRAF mutations respond to Vemurafenib.

"Because we have sequenced lots of patient genomes, the major mutations have already been discovered. The big push now is how to use the knowledge to improve the treatment and management of cancer patients. That's what it's all about."

Reshmi Parameswaran

Reshmi Parameswaran

Reshmi Parameswaran, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Departments of Medicine, Pediatrics, and Pathology at the medical school. She is a member of Case CCC. Her specialty: immunotherapy/immuno-oncology.

"It's a very exciting time in immunotherapy. Progress in the last decade has been immense.

"One of the most recent advancements is called adoptive cell transfer. It's taking patient blood and removing the most common immune cells [such as T cells]. If they are low in number, we can make more of them, inject these cells back into the patient and, because they're in larger numbers, they can kill the cancer cells.

"Normally, immune cells move around the body looking for ‘not normal' cells, like cancer cells or bacterial or viral infected cells, and destroy those cells. Unfortunately, cancer cells often escape from these ‘immune cell patrols' and grow out of control.

IMAGE: ciphotos/iStock/Getty Images Plus

IMAGE: ciphotos/iStock/Getty Images Plus"Now we have a landmark advancement in immunotherapy named CAR-T cells to address that.

"With the CAR-T process, we are removing T cells from patients and introducing into them a particle of DNA that gives them the specificity and a boost signal to kill only cancer cells. These modified T cells—now called CAR-T cells—are reinjected back into patients. They are more powerful in killing cancer than T cells and also spare most of the normal cells.

"CAR-T doesn't work for all cancers, but right now it is being used for leukemia and lymphoma patients. In some studies [conducted at various research sites], up to 90% of pediatric leukemia patients treated with this therapy are in remission. We still don't know if the disease will come back. Research is being done now on how we can use CAR-T cells for solid tumors."

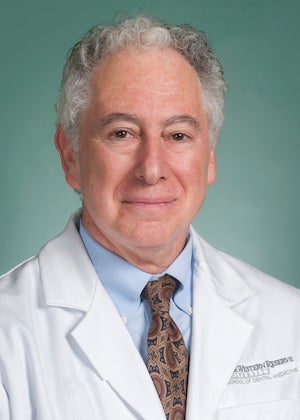

Aaron Weinberg

Aaron Weinberg

Aaron Weinberg, DMD, PhD, is a professor in and chair of the Department of Biological Sciences at the School of Dental Medicine. He also is a member of the Case CCC. His research focus: oral and oropharyngeal cancers.

"In regard to oral cancer, there are pockets of epidemics in the world that have caught the attention of the World Health Organization, and a lot of it is due to the consistent and historic use of betel nut, a stimulant that is very much like nicotine.

"Close to 700 million people use it. It usually sits between the cheek and the gum tissue. Between 7% and 10% of people using this develop oral cancer.

"By the time people have symptoms … the cancer has metastasized to the lymph nodes, and the prognosis is pretty bad.

"The survival rate is about 50%, but if people could be monitored on a regular basis, and if the lesion is found early on and removed, the survival rate is greater than 92%. In a lot of low socioeconomic countries, especially India, where betel nut use is rampant, the monitoring process is nonexistent.

"Under development right now is a point-of-care device that a field nurse could use to determine if an incipient lesion is cancerous. Within half an hour, it could determine whether cells from a swab are indeed cancerous.

"It's important both from the perspective of cost and it's a noninvasive approach to a huge epidemic. You can't take the lab into the field, but you can take the device into the field."

Jill Barnholtz-Sloan

Jill Barnholtz-Sloan

Jill Barnholtz-Sloan, PhD, is the Sally S. Morley Designated Professor in Brain Tumor Research at the medical school, associate director for data sciences at Case CCC, and associate director for translational informatics at Cleveland Institute for Computational Biology, whose member organizations include CWRU. Her specialty: big data.

"The term big data came from the realization that, with the adoption of the electronic health record, we were generating enormous amounts of data on patients. If we can utilize all of this data together, then maybe we can make new discoveries.

"Having access to data from large sets of cancer patients beyond just your institution may allow you to look at specific subsets of patients who have a particular disease or a disease with specific characteristics. Maybe you can learn something about them that you would not be able to at your single institution. But with a large data set, you can find enough patients to make your findings meaningful.

IMAGE: Shuoshu/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images

IMAGE: Shuoshu/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images"For example, the Cancer Genome Atlas project [an effort to accelerate understanding of the molecular basis of cancer using big data] has led to changes in how we diagnose brain tumors. Based in part on what researchers have learned from the project, the World Health Organization now incorporates very specific molecular markers into their diagnosis coding scheme in order to accurately make a brain tumor diagnosis.

"In addition, once a new cancer drug is used for a while, we can look at all the patients in a health system who received it and ask: ‘Do we still see the same positive effect of that drug?' In addition, we are already seeing institutions using data to predict, for example, the probability of a readmission to the hospital or an emergency room visit."

Ronald Hickman

Ronald Hickman

Ronald Hickman, PhD, RN (CWR '00; NUR '06, '13; GRS '08, nursing), an associate professor and the associate dean for research at the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing. His specialty: end-of-life cancer care.

"Medicine has come to understand the importance of end-of-life cancer care and to appreciate factors that influence care decisions, outcomes, as well as some potential barriers related to the way patients, their families and their providers communicate in planning for the end of life.

"With cancer, there's been an orientation toward always prolonging life and curative treatments. We've made progress to help enhance survivorship among patients with advanced cancer, but with every decision there are tradeoffs.

"I don't know if we've always been as forthcoming about what those tradeoffs will look like, in terms of symptoms, costs and other consequences. We've made some steps in a positive direction to have those conversations early, proactively and on an ongoing basis.

"There's more focus on engaging the patient, family and other stakeholders—physicians, oncologists, nurses—in discussions really centered on issues related to quality of life and care that meets patient and family goals.

"Families have become a significant contributor to the conversation, in helping [clinicians] understand the patient, the family's values, and concerns that are related to spirituality and existential issues that often arise.

"Patients are now getting holistic services. They're seeing psychosocial practitioners, social workers and counselors. They're getting their spiritual needs met. There are supports that are directed to the patient, but also at the family level as well.

"Conversations are happening earlier, and oftentimes they're revisited. These are now common-occurring events that are part of routine cancer care."

*The conversations were edited for length.