connect

Knockout

How alumnus David Dinkins Jr. became boxing’s premier producer

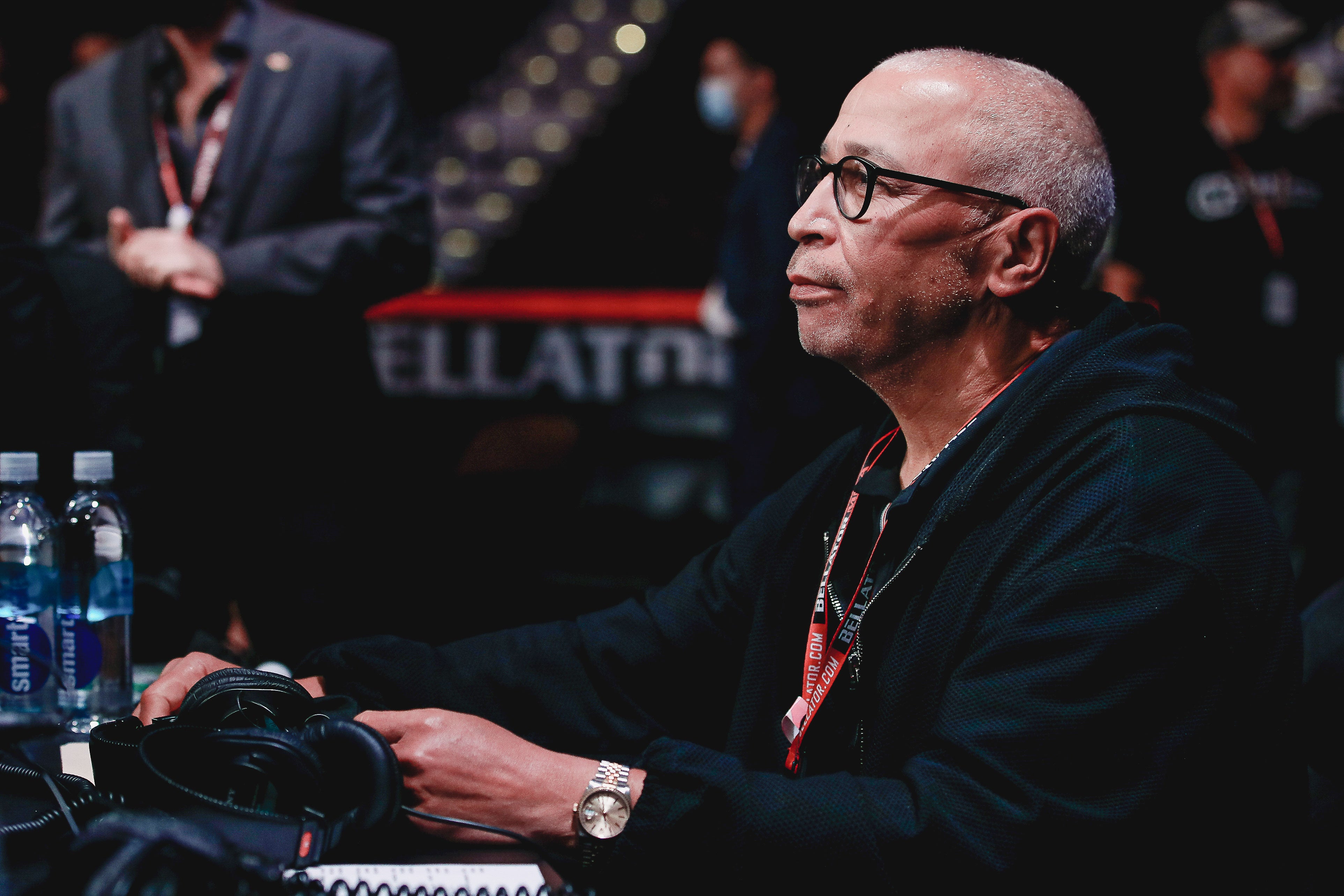

Photo: Courtesy of Showtime Sports

Photo: Courtesy of Showtime SportsDavid Dinkins Jr. served as the executive producer of the Bellator MMA (mixed martial arts) matchups in June on Showtime.

When Mike Tyson infamously bit off part of the ear of then-boxing champion Evander Holyfield in their June 1997 heavyweight fight, it shocked the world. But in the TV control room that night, producer David Dinkins Jr. (WRC ’76; GRS ’77, communication sciences) was ready.

He quickly assembled a camera operator, audio technician and reporter Jim Gray to catch the disqualified Tyson outside his locker room, resulting in an interview that earned Gray an Emmy. “In my job, you have to be prepared for the unexpected,” Dinkins said. “And that was certainly unexpected.”

Dinkins, now senior vice president and executive producer of Showtime Sports, has spent most of his career producing televised sporting events, including everything from the Olympics to Major League Baseball’s World Series to major boxing matches. And he’s amassed his own fan base among colleagues who know him as a top-notch producer and coach.

“Showtime Sports is the leader in combat sports production, and David Dinkins has been one of the architects of the franchise,” said Marc Youngblood, a senior writer and producer at Showtime who’s worked with Dinkins for 20 years. He considers Dinkins a mentor who’s helped him sharpen his scripts and feature productions.

Yet Dinkins didn’t initially set his sights on a media career. As he completed his undergraduate degree at Case Western Reserve, Dinkins considered attending law school—the path taken by his father, David Dinkins, who later became New York City’s first Black mayor.

But then Lowell Lynn, who was an assistant professor of speech communication at CWRU, connected Dinkins to an NBC fellowship that allowed him to earn his master’s degree in communication sciences and work at the network affiliate in Cleveland. The experience kick-started a 44-year career in television production. “I owe Professor Lynn a debt of gratitude,” said Dinkins, who took Lynn’s classes as both an undergraduate and a graduate student. “I would not probably have gotten on this track—surely not that early—without his encouragement and guidance.”

Dinkins succeeded despite the discrimination he faced from athletes, sporting venues and dismissive peers as a young Black man in an industry with a dearth of Black representation. “Especially those that ranked higher than me, and their superiors, weren’t used to dealing with people that came from my community—and really weren’t of the mindset to be inclusive,” said Dinkins. “They’d look at you with limited expectations, which is insulting. So, you had to continually prove yourself.”

He’s done far more than that. Dinkins has worked with legends such as Muhammad Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard; produced storied matches, including the 2015 “Fight of the Century” between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao; and won four Emmys—two for his work producing NFL games at CBS and two for his boxing work at Showtime.

“He’s certainly the leading boxing producer in the field,” said Mike Arnold, a director at CBS Sports, who was hired by Dinkins as a production assistant in 1978 and has directed the broadcast of six Super Bowls since 2007.

Dinkins attributes his success to having “the right skill set,” particularly knowing how to surround himself with “a really terrific team.”

After decades working in production control rooms, Dinkins still feels the joy of knowing he’s where he’s meant to be. For some, the environment—with its bright wall of monitors, constant din, and regular check-ins with stage managers, statisticians, directors and reporters—produces sensory overload. Not Dinkins. “It’s another home for me,” he said.