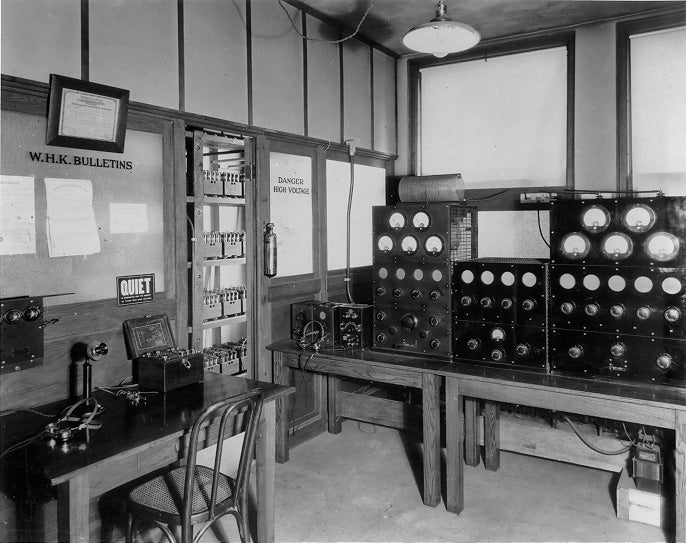

RADIO. In Cleveland, the development of radio went through 3 distinct phases: an initial, largely experimental period which gradually became commercialized; a second when radio flourished as a commercial medium; and the third following WORLD WAR II, when radio strove to cope with television and increasing competition within its own industry. Cleveland's first radio station was WHK, which went on the air early in 1922. Later that year WJAX began broadcasting, followed in 1923 by WTAM, sharing time on the same 390-meter frequency. Eventually WJAX was sold to WTAM's owner, WILLARD STORAGE BATTERY, ensuring WTAM a clear channel at 390 meters. In 1927 WJAY began to operate under a sunup-to-sundown license. WGAR joined the Cleveland group in Dec. 1930. The 1920s saw an entertainment boom in downtown Cleveland, and at E. 105th St., with the construction of palatial new theaters featuring vaudeville and Hollywood films. Restaurants provided social dancing during dinner and after-theater hours. However, local stations countered by broadcasting from restaurants, hotel dining rooms, and even theater stages, building audiences both at home and in the various venues. Radio listings for 1925-26 show broadcasts from the HOTEL CLEVELAND, the Rainbow Room at the Hotel Winton, the STATE THEATER, the HOTEL STATLER, the Bamboo Gardens Orchestra, and the HOLLENDEN HOTEL.

Soon 3 realities emerged: advertising was necessary for income; planned, exciting programming was imperative; and a professional approach to sales and promotion was an immediate need. Radio advertising itself was opposed by many who believed the new medium should be used to educate and raise levels of thought. Broadcasters also had to prove to potential advertisers that their dollars were actually accomplishing something. Well-known entertainers proved to be the answer and helped draw both audiences and advertisers. Two such entertainers were Cartwright "Pinky" Hunter, a singer long identified with Emerson Gill's Orchestra, and "Ev" Jones, popular bandleader whose WTAM programs brought him and the station a loyal following.

By 1926 radio was no longer a novelty. Believing that local stations were not equipped financially to sustain quality programming, many felt that New York, with its exemplary stations, WEAF and WJZ, should share their excellence with listeners everywhere. In Sept. 1926 the Radio Corp. of America announced the formation of the Natl. Broadcasting Co. for that purpose. Within 3 months came the announcement of a second, rival network, which by autumn of 1928 had been purchased by Wm. Paley and renamed the Columbia Broadcasting System. NBC initiated 2 networks, to comply with government pressure that broadcasters should inform and educate, as well as entertain. David Sarnoff chose WEAF to entertain as the Red Network, and WJZ to inform as the Blue Network. Almost immediately the "Red" Network courted WTAM to become its Cleveland affiliate, while CBS approached WHK in the same manner. NBC's "Blue" Network was picked up by WGAR when it debuted in 1930. WJAY, because of its sunrise-sunset license, remained independent until its purchase by the PLAIN DEALER in 1937, with the new call letters WCLE. In its 10 years (1927-37), under Monroe F. Rubin and general manager Grant C. Melrose, WJAY made a strong impact on Cleveland radio as a proving ground for aspiring local and area talent and as an outlet for Cleveland's large ethnic population. From the ranks of its ethnic programmers came FREDERICK C. WOLF, who would found WDOK in 1950.

As the 1930s opened, stations competed at both local and network levels as the market grew. Every strategy was used. Announcers began to vary their deliveries, from "hard sell" to "intimate." Stations promoted themselves with billboards and public appearances of station personalities. Better equipment made the medium more effective. Advertising agencies were retained to promote stations in the print media. That led to agencies' representing sponsors. In the 1930s, both networks and local stations fine-tuned programming to match certain audiences. That resulted in daytime dramas (soaps). Evening programming, with variety shows hosted by established stars such as Rudy Vallee, Bing Crosby, and Al Jolson, appeared for general audiences. Quiz shows, born in the 1930s, also found a niche in evening programming. These influences quickly reached the local level, where they engendered a trend toward a more conversational "everydayness" on the air. Two-person shows began, such as "Ethel and Ben" (homemakers) on WGAR, "Mildred and Gloria," a women's show, on WTAM, and "Just Married" on WJAY, an improvisational drama show ad-libbed from a synopsis sheet prepared by creator Edyth Fern Melrose.

In 1937 CBS named WGAR as its local affiliate, whereupon WHK accepted the NBC "Blue" affiliation and that of the newly arrived Mutual Broadcasting System. The year before, WHK had completed the first full season of radio coverage of CLEVELAND INDIANS BASEBALL games and had also sent a radio newsman to cover a flood disaster on the Ohio River. Both actions were the result of increasing technical sophistication. The growing role of radio in local and national life was exemplified by its place in the GREAT LAKES EXPOSITION, in which PUBLIC AUDITORIUM was transformed into a studio hosting network prime-time programs throughout the summers of 1936-37. By the end of the 1930s, 6 principal areas of programming had evolved: news, remote broadcasts, sports, ethnic programming, religion, and in-house scripted and produced productions of major size.

Radio stations deferred from all-out news activity in the 1930s. They could not compete adequately with newspapers on in-depth coverage. Radio's one peculiar strength was in its immediacy, which was what stations exploited. They developed the headline style of succinct reporting, and, when possible, brief interviews with witnesses or participants. Stations recognized the importance of regularly scheduled newscasts throughout each day; weather reports and traffic conditions were standard auxiliaries.

Remote broadcasts normally required 1 announcer and 1 technician, responsible for gear and setup. The 1930s witnessed regularly scheduled broadcasts from the major downtown hotel dining rooms and nightclubs. In the late 1930s, concert pickups from SEVERANCE HALL and summer concerts at Public Auditorium were routinely made. The earliest efforts in sportscasting came in 1922 when WHK and WJAX included scores and brief highlights in their local newscasts. WTAM soon became ascendant in sports, with TOM MANNING becoming the area's best-known announcer from his association with the Cleveland Indians; by 1930 he was doing play-by-play from LEAGUE PARK. Other notable local sportscasters included JOHN "JACK" GRANEY, Jimmy Dudley, Ken Coleman, Bob Neal, and Van Patrick in the 1930s and 1940s, and later, GIB SHANLEY, Joe Tait, and NEVILLE "NEV" CHANDLER. Ethnic programming, begun at WJAY, was eventually taken up by other stations (usually on Sunday mornings), including WGAR, WHK, and WERE. In 1950 WDOK picked up where WJAY and WGAR had left off, followed by WXEN and WZAK in the early 1960s. Such activity declined in the 1970s, and by 1985 Cleveland's Public Service station, WCPN, was the major purveyor of ethnic programming.

By the early 1940s, local stations were well-equipped to cover World War II, both internationally and domestically. On the domestic front, in 1943 the Federal Communications Commission enforced a long-deferred antimonopoly action against NBC, resulting in its divestment of the "Blue" Network as the American Broadcasting Co., which chose as its Cleveland affiliate the city's newest radio station, WJW, owned by the O'Neill family of Akron. The edict also forced the closing of WCLE by the Plain Dealer as a Cleveland station, forbidding any person or group to own more than 1 radio station in a single market (the Plain Dealer also owned WHK). To assist the war effort, WHK, under writer-producer Leslie Biebl, produced "Victory Time," a series of variety programs sponsored by Thompson Prods. (see TRW). At WGAR, SIDNEY ANDORN wrote and produced a major variety production featuring soloists, chorus, and orchestra for Jack & Heintz (see LEAR SIEGLER), depicting the company's geared-up efforts in war production. WGAR's award-winning "Serenade for Smoothies," sponsored by OHIO BELL in the interests of recruiting women, featured soloists, a girl's quartet, and staff orchestra playing before audiences in the Little Theater of Public Hall. Wayne Mack was writer and producer. Local stations sent correspondents to both the European and Pacific war theaters to interview Cleveland men and to send back their greetings.

As World War II ended in 1945, interest in sports rose to fever pitch. The Tribe's Hooper rating in the world championship year of 1948 was 60%; the fortunate station was WJW, the flagship of a special 6-station Ohio network. The full games were carried on WJW-FM, since WJW-AM, with its ABC commitments, was available only part of the time. In that year there were more FM radio sets sold in Cleveland than in any other market in the country. Licenses for Edwin Armstrong's "static-free" frequency modulation (FM) concept of radio transmission were first granted in 1940-41. Most Cleveland stations began making applications over the decade.

TELEVISION came to Cleveland in 1947 and ushered in the third period of local radio history. By 1950 3 television stations were operational in Cleveland, plus radio newcomers WDOK, WSRS, and WJMO. During the transitional 1950s, the medium began to evolve into the multifaceted, loosely structured industry that it became by the 1980s. The networks remained intact during the decade, but independent local stations introduced, from motives of economy, a new and somewhat different type of announcer, the disc jockey. By a curious coincidence, the DJ and ROCK 'N' ROLL music arrived at about the same time; clearly meant for each other, they would dominate American music for the next 20 years. Two other forces were present as radio headed into the 1960s. One was the proliferation of new stations whose formats were quite individual and different, such as WCLV, devoted entirely to the fine arts and concert music, WCRF, a religious station, and WSUM, devoted to community service. This trend pointed to considerable fragmentation of the listening audience.

The other force was the imposing effect of rapidly developing technology. The development of transistorized portable radios and stereophonic broadcasting gave new flexibility to the medium. Perhaps the greatest effect locally was the ascendance of FM broadcasting. In 1965 WDOK was purchased by the Westchester Radio Corp., which immediately transferred its established format to the FM frequency and re-introduced the AM property and its call letters into that of a rock 'n' roll station, WIXY. The resulting outrage was great, but subsided when listeners discovered FM to be superior in quality. The experiment gained national attention, and considerably influenced the emergence of FM into a dominant role in radio. In the late 1960s, the FCC decreed that FM stations could no longer be written off as duplicators of AM programming, but must provide a responsible share of their own creative product. That helped push FM toward center stage, as did the rapid accommodation of stereophonic sound to FM by "splitting" the FM wave. Another boon of that technology was the subcarrier (SCA), which was used in "storecasting" by the Muzak Corp. and in special hookups for ethnic broadcasting, requiring modified receivers, as well as "schoolcasting," in use in some schools (parochial) outside the WBOE service of the Cleveland Board of Education. It was made available by Radio Seaway, Inc., owner of WCLV.

In the 1960s and 1970s, radio turned from its original purpose to the new role of specialist, in which each station catered solely to the taste of a certain type of listener—hence "narrowcasting," as opposed to broadcasting. Such further fragmentation led to a feverish hunt for listeners. Promotions to gain an audience became, at times, juvenile and indiscreet. The FCC was criticized for its laxity in surveillance of program content but held adamantly to its position of neutrality, stating that it could not "police" 10,000 radio stations. This led to a gradual deregulation of radio, beginning in the mid-1970s and completed early in the 1980s. The number of stations in northern Ohio climbed to more than 40. Formats were no longer sacrosanct; a losing format was simply changed. For example, WIXY became WBBG in the 1970s, when the station decided to program the Big Band music of the 1940s for the 50-and-over segment of the population.

Perhaps Cleveland's outstanding example of intrepid programming during this volatile period was that of WCLV, the fine-arts station, which, despite a relatively small share of the listener market, remained one of the area's most consistent formats. On the other side of the musical spectrum, WMMS managed to hold a consistent rock format for a number of years and to achieve national stature for its programming and audience size. Elsewhere on the dial, Cleveland's radio industry in the 1980s was still largely in turmoil, with programming shifts, personality changes, and the rapid purchase and sale of stations.

By the 1990s AM radio was particularly depressed, with few stations emulating the success story of WRMR with its nostalgia format. With the exit of WIXY in 1976, Cleveland had become the first major radio market without a top-40 rock AM station. An entire generation was thus raised on FM, oblivious to the AM experience. Many of Cleveland's AM stations consequently were turning to time-brokering agreements, in which the station abdicated its programming function to independent producers. Through all such vicissitudes, however, radio remained a viable force in the community. Its unobtrusive nature, making it an effective medium even when its audience engaged in other activities, coupled with the miniaturization made possible by technology, made it as great a part of the lives of Greater Clevelanders as ever.

Wayne Mack

List of Radio and Television Stations (by Year)