GAY BARS IN CLEVEAND have been in existence since at least the 1940s and have served as important sites for the city’s LGBTQ community to socialize, organize, and distribute information and resources.

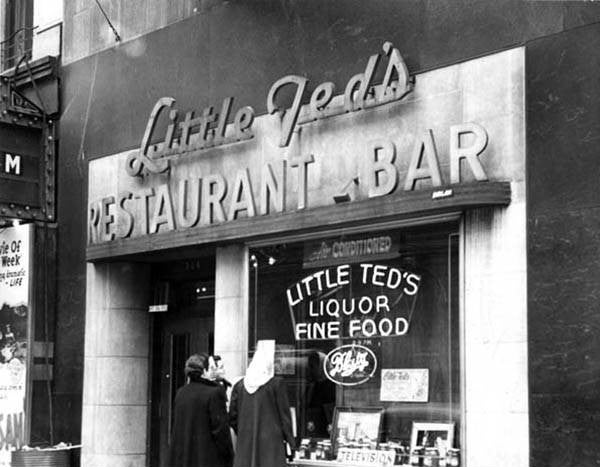

In the 1940s, there were several bars for gay men in business. These included the CADILLAC LOUNGE, a formal bar in the Schofield Building on Euclid Avenue which had live piano performances and artwork by WILLIAM C. GRAUER, a bar called Little Ted’s, which was situated under a restaurant of the same name near the CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY, as well as a bar called Mac & Jerry’s, which was not exclusively gay but was a popular spot for the city’s industrial workers. Some gay bars in the 1940s were also part of the early drag scene. At the time, performers known as “female impersonators” would dress up in elegant gowns and makeup to sing or play live music at venues such as Cleveland’s Viking Club and the Musical Bar.

Little Ted's Restaurant and Bar in 1949

In the 1950s and 1960s, Cleveland’s gay bar scene grew considerably, as did the number of bars that were not exclusively gay, but gay-friendly. Adele’s Bar at East 115th Street and Euclid Avenue was one such spot, where students from the nearby CASE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY and WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY would gather alongside members of Cleveland’s gay community. Another popular spot was The Orchid, which opened at East 105th Street and Euclid Avenue before moving to another location downtown. Gay bars also opened in the suburbs surrounding Cleveland. The King’s Room in CLEVELAND HEIGHTS, situated at Taylor and Cedar, had an almost exclusively gay patronage, as did the Shaker Club in SHAKER SQUARE.

In the 1970s, Cleveland had dozens of gay bars frequented by gay men and lesbians in the community. The Leather Stallion was a popular gay bar that opened in the 1970s in the downtown area and has remained open since. The CADILLAC LOUNGE closed in late 1970, but other bars owned by Gloria Lenihan like the Pickwood Lounge on Clifton Avenue remained popular spots for Cleveland’s gay and lesbian community. During this time, the area around Clifton Boulevard was already a significant part of the gay bar scene that included other venues the Nantucket Lounge, across from the Pickwood. This area is still home to many gay bars today (2022).

As the gay liberation took hold in Cleveland in the 1970s, members of the gay community created new gathering spaces that served as alternatives to the gay bars. In 1977, the opening of the offices of LESBIAN/GAY COMMUNITY SERVICE CENTER OF GREATER CLEVELAND provided a space for members of the gay community to socialize, organize politically, and share resources and information. Other organizations, such as OVEN PRODUCTIONS, provided space for lesbians to come together for cultural events like art exhibits, films, concerts, and plays. Gay bars maintained their presence in Cleveland, and they were significant for gay publications like HIGH GEAR which used them as points of distribution, but they were no longer the only places in which to socialize openly and safely.

Although Cleveland’s gay bars have been valuable spaces for members of the gay community to gather, their patrons have not always been treated in an equitable manner.

Discrimination against Black patrons at gay bars has been a significant problem that many members of the gay community have mobilized against. The Midwest Regional Discrimination Response System, a project of Black and White Men Together, formed in order to report instances of racial discrimination within the gay and lesbian community and discrimination against the community. In 1985, the organization mobilized against the Ritz, a bar in Cleveland that accepted members of the gay community on Sundays, which had been the subject of complaints of discrimination against Black men and women attempting to enter. The organization responded by organizing volunteers to test the discriminatory policy and pursued legal action against the bar.

Discrimination against women at gay bars has also served as a point of mobilization for the gay community. In 1975, the Cleveland Gay Political Union boycotted the 620 Club on Frankfort Avenue because it refused to admit women. In 1977, reporters for the PLAIN DEALER writing an article on the gay bar scene noted the bar’s continued policies against admitting women. The first time that the reporters had tried to gain entry, the doorman had responded, “This is a men’s bar. No ladies around.” In 1985, the Midwest Regional Discrimination Response Service received complaints against the 620 Club for refusing to admit women. Other bars like the Leather Stallion had similar policies. In 1977, when a reporter asked why the door to the women’s restroom in the bar had been boarded over, the manager stated that, “We don’t serve women.” After years of resistance and a change in ownership, the Leather Stallion began to allow women in the late 1980s.

Today (2022), although there are numerous spaces in Cleveland for LGBTQ people to gather, gay bars still have a strong presence. While early gay bars were often downtown or on Cleveland’s East Side, most gay bars today are situated on the city’s West Side. These include Vibe Bar & Patio on Lorain Avenue around West 117th Street, Twist on Clifton Boulevard, Cocktails and The Hawk on Detroit Avenue, Shade in Cleveland’s OLD BROOKLYN neighborhood, and the Leather Stallion, which holds the record as Cleveland’s oldest operating gay bar.

Gay bars in Cleveland have served as important spaces for members of the LGBTQ to gather since the 1940s. Like other institutions, gay bars have had discriminatory policies which at times have served as points of mobilization for gay activists who sought to change them. While gay bars are no longer the only places for LGBTQ Clevelanders to safely gather, they remain important institutions for the community today.

Sidney Negron

Last Updated: 4/5/2022

Finding aid for the Lesbian-Gay Community Center of Greater Cleveland Records

Northeast Ohio LGBT Oral History Project Recordings and Transcripts

View image at Cleveland Memory

Kelsey, John. “The Cleveland bar scene in the forties.” In Lavender Culture. Eds. Karla Jay and Allen Young. New York: New York University Press, 1994.