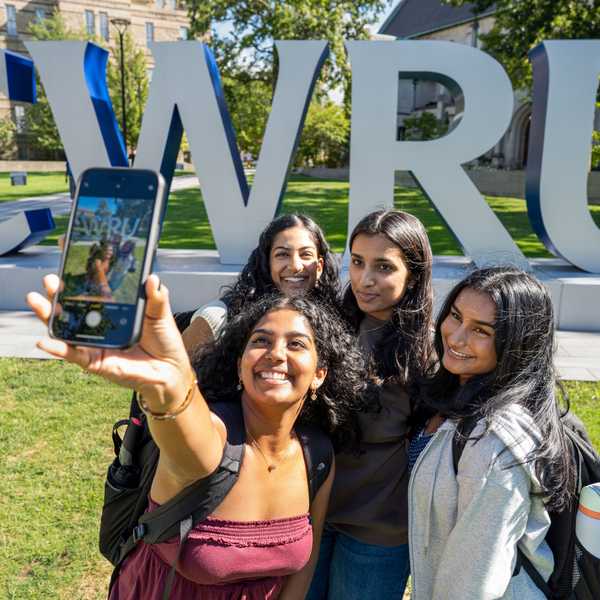

At Case Western Reserve University, we think big.

But we don't just think—we do.

In labs and classrooms, we spend each day asking—and discovering—how

to solve the biggest issues of today and tomorrow.

Expand Your Education

With hundreds of programs in a variety of formats, we're confident you'll find an option that fits your goals.

The CWRU Difference

Research and Innovation

An ecosystem for translational, collaborative research

Using nanomedicine and biomedical ultrasound, Agata A. Exner's lab is developing more precise ways of diagnosing and treating cancers. She's collaborating with CWRU colleagues on the technology's potential commercial application in prostate cancer.

Find Yourself in Cleveland

Our hometown offers the best of both worlds: big-city opportunities in a tight-knit community. Here, you can immerse yourself in our robust arts scene, explore your entrepreneurial spirit, take in a pro sports win, enjoy our 50,000+ acres of parks and green spaces, or explore any number of other exciting adventures.

More to Explore

No matter your interest, CWRU offers opportunities to match—from training in the arts to driving groundbreaking research to competing on the field.