Can you speak up in your team?

By Tyler Reimschisel, MD, MHPE

“A sense of confidence that your voice is valued. A sense of permission for candor.” —Amy Edmondson

In my last article, I mentioned that I wanted to discuss how to test the judgments, inferences and assumptions that we automatically make during teamwork so that we do not mistakenly step on the top rung of the ladder of inference. Before I discuss that important topic, I would like to review a teamwork concept that is likely to be familiar to many of you: psychological safety. The literature on psychological safety is quite extensive, and in this article I will only be able to briefly summarize this essential component of high-impact teamwork.

Before reading further, please take a moment to jot down or make a mental note of how you would define “psychological safety.” We will come back to your personal definition a little later.

What is psychological safety?

Amy Edmondson, Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School, states that a team has psychological safety when people at work “feel comfortable sharing concerns and mistakes without fear of embarrassment or retribution. They are confident that they can speak up and won’t be humiliated, ignored, or blamed. They know they can ask questions when they are unsure about something. They tend to trust and respect their colleagues,” (Edmondson, 2019).

In a nice video summary of psychological safety, she states that it is a “shared belief that the environment is conducive to interpersonal risks, like asking for help, admitting mistakes and criticizing a project,” (Green, 2020).

Why is psychological safety important?

A few years ago, a Google study showed psychological safety was the most important factor in determining whether a team at Google was effective (re:Work, 2019). This study, like many others, shows that the influence of psychological safety cannot be underestimated. It also raises another aspect of the definition of psychological safety. Psychological safety is a characteristic of a team, not of an individual on a team. Furthermore, the culture or ecosystem of a team enhances or diminishes psychological safety.

What psychological safety isn’t.

One of the reasons that I wanted you to write down how you would personally define psychological safety is that I find many people have a mistaken notion of what it is. It is not simply being nice or kind to one another. In fact, as the quote at the top of the article points out, it can mean speaking up candidly to share your views, and that can be perceived as being unkind in challenging situations. It is also not permission to whine or complain simply to vent your feelings or emotions. That can compromise the morale and overall quality of the workplace environment. It is not applause for all of your ideas or getting your way on the team all of the time as that is impractical and is focused more on you as an individual and less on the well-being and productivity of the team.

In addition, it is not the absence of conflict. Instead, teams with good psychological safety may have a lot of overt conflict, probably more than teams with low psychological safety. Yet the teams with high levels of psychological safety are able to manage the conflict and leverage it into growth and improvement for the team.

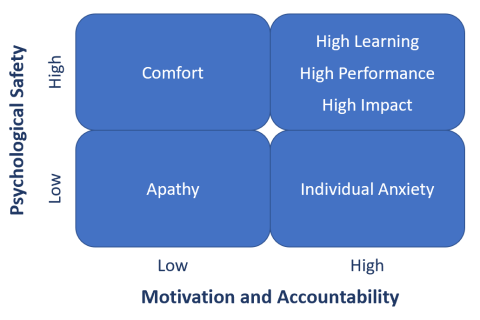

The biggest misunderstanding about psychological safety that I have seen is that it can be claimed as license to slack off, be lazy, gossip about team members, or take other unprofessional and immature actions that undermine the work of the team. Psychological safety is not permission to be unmotivated nor is it a shield against accountability to the team and its leaders. Edmondson uses the following 2 x 2 table to explain the relationship between psychological safety on the one hand and motivation and accountability on the other.

On the other hand, a workplace that is low in psychological safety but high in motivation and personal and team accountability (lower right quadrant) will likely generate a lot of anxiety for the team members when there are differences of opinions, mistakes, or conflict. This environment can certainly diminish the team’s performance and impact. A workplace that is high in psychological safety but low in motivation and personal and team accountability (upper left quadrant) may be a comfortable place to work, but it won’t be as productive and satisfying as it could be.

Ideally, a team has both high psychological safety as well as high motivation and accountability (upper right quadrant) because this combination leads to high learning, high performance, and high impact.

Edmondson uses the analogy of brake and gas pedals in a vehicle. Increasing psychological safety is like letting up on the brake pedal, and increasing motivation and accountability are like depressing the gas pedal. To move your team forward toward achieving its goals, it is best to both let up on the brake pedal and depress the gas pedal.

How do you create and grow psychological safety?

Edmondson provides three basic steps for creating psychological safety. These steps can be taken by any member of the team, yet it is particularly helpful if the leaders of the team intentionally implement these steps.

- Frame the team situation as a learning problem. Psychological safety is especially crucial in situations where there is both uncertainty and the need for interdependence among the team members. In these situations, the leadership should clearly state that the team, teams or organization are in challenging and uncharted waters. Yet if the team works together, it can become a wonderful learning opportunity that could strengthen the team. As Edmondson points out, this approach helps to set the stage for why having input from everyone on the team is important.

- Acknowledge your own fallibility. Next, given the complexity and uncertainty of the situation, it is important for team leaders and other team members to admit their own limitations and fallibility. In situations where I need the team to feel comfortable speaking up, I like to say that I am not sure what the solution may be, but I do know that I cannot generate the best solutions on my own. That requires interdependent and collective team conversations. In fact, I may miss something, and I need everyone on the team to speak up.

For leaders who want to start fostering psychological safety among their team, one practical way to apply this step is to apologize to the team for not taking these steps sooner. In addition, a recent study by Coutifaris and Grant showed that one of the most effective ways for leaders to build psychological safety in a team is to share negative feedback that they have received about themselves with the team. This is believed to be effective because it demonstrates vulnerability, and being genuinely vulnerable is a potent way for leaders to deepen psychological safety within their team (Coutifaris and Grant, 2021).

- Model curiosity. But simply saying you want people to speak up may not be enough. In addition, team members and their leaders should proactively welcome input by asking questions…a lot of them. Edmondson describes this as creating a necessity for others to speak up and making it a bit uncomfortable for them to remain silent. Then when team members come forward with ideas, suggestions, or acknowledgement of mistakes or misgivings, it is important that leaders and other team members welcome those comments so that over time psychological safety is fostered.

I want to close with an elaboration of Edmondson’s metaphor of psychological safety as the brake pedal on the teamwork vehicle while motivation and accountability are the gas pedal. We value the brake and gas pedals in our vehicles because they help us safely get to where we want to go, but we do not sit in our car admiring them.

Similarly, the goal of teamwork is not psychological safety itself. Instead, high levels of psychological safety help teams reach their goal of being a high-impact team with excellent internal dynamics, superb external performance, and a positive influence on the team’s patients, clients and organizational systems.

References

Coutifaris CGV and Grant AM. Taking your team behind the curtain: the effects of leader feedback-sharing and feedback-seeking on team psychological safety. Organization Science. August 17, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1498.

Edmondson A. The importance of psychological safety. August 5, 2000. [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eP6guvRt0U0.

Edmondson A. The Fearless Organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation and growth. Wiley, 2019: xvi.

Green D. How do you create psychological safety at work? Interview with Amy Edmondson. July 14, 2020. [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_35pAviSnI.

re:Work. Guide: Understanding team effectiveness. Google, 2019. https://rework.withgoogle.com/print/guides/5721312655835136/.