Table of contents:

- Overview of the weekend

- An Evening with Elaine Nichols

- National Museum of African American History and Culture

- The Other Madisons with Bettye Kearse

- Reflections Joannie Brooks Parker

Overview of the weekend

Last month, the African American Alumni Association of Case Western Reserve made its first out-of-state trip since it became an official university affinity group in 2009. Their pilgrimage to Washington, D.C., in March harkened back to the group’s early days, when alumni would organize reunions around the country in each other’s homes.

This time, they had the logistical support of CWRU staff and were joined by President Eric W. Kaler and Mrs. Karen F. Kaler, in addition to D.C./Baltimore Chapter alumni. And while they didn’t meet in a house, they began the weekend by hearing from a local alumna.

Elaine Nichols (SAS ‘80), supervisory curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), kicked things off with a presentation about her work and the following day, attendees were given access to the museum for a self-guided tour.

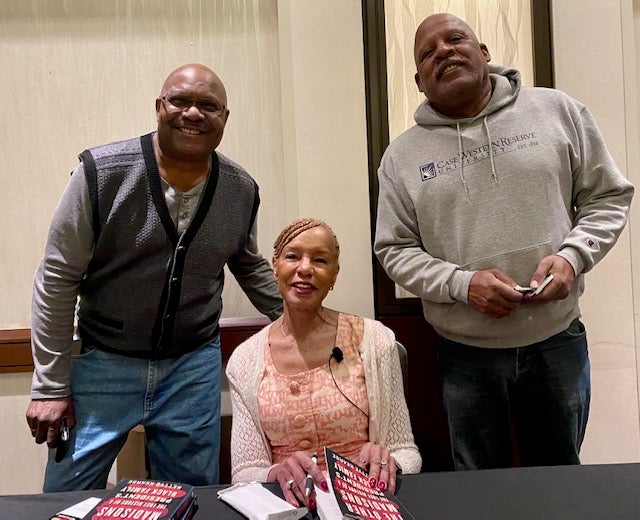

Bookending the trip was a breakfast with New Mexico alumna Bettye Kearse (MED ’79), author of The Other Madisons: The Lost History of a President's Black Family, who shared her story and a vibrant discussion with Mrs. Kaler.

“I’m a history nerd and going to the NMAAHC was a personal goal of mine,” said Tiarra Thomas (CWR ’12), president of the African American Alumni Association. “It was incredible to learn so much about our history we wouldn’t know otherwise, and to share that with each other. The fact that we were able to come together in that way was absolutely amazing.”

If you missed the weekend, Thomas encourages you to start getting involved however you can—with the university and with each other. “We have a strong network of alumni all over the country,” she said. “Take advantage of that! Find your CWRU people, wherever you are, and keep those connections alive.”

More than 100 attendees enjoyed the weekend’s activities, and some shared their reflections with us. Read more about each event below and check out photos from the trip.

An Evening With Elaine Nichols

Elaine Nichols has been fascinated by people’s stories for as long as she can remember. As senior curator of culture at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), she takes seriously her responsibility for collecting objects and information to help illuminate the history of the African American community. On March 10, she shared her own story and those of others with attendees of the African American Alumni Association’s Weekend in Washington. In her words, “everyone’s story matters.”

Nichols credits her time at Case Western Reserve University with teaching her to be tolerant and to listen—lessons that have served her well in her career as a curator, which began at the South Carolina State Museum. In 2009, she was recruited by Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the NMAAHC and Rex Ellis, Associate Director of the Office of Curatorial Affairs, to participate in the Save Our African American Treasures program. The program, which toured the nation, sought to help people document and preserve objects associated with their families’ heritage. It also laid the foundation for the museum, which opened seven years later in September 2016.

In addition to overseeing a team, Nichols is responsible for fashion, dolls, toys, games and textile collections. This includes the Black Fashion Museum collection, founded by Lois Alexander Lane, and the Ebony Fashion Fair collection, created by Eunice Johnson. The stories behind these collections evoke a sense of pride in addition to promoting the legacies of Black fashion influencers, whose names are less known than their white counterparts. But Nichols had new perspectives to offer on even the most widely recognized figures in Black history.

Rosa Parks is often depicted as a demure lady who was simply too tired to give up her seat to a white man on a bus in 1955. NMAAHC visitors, however, learn about her longstanding commitment to activism and her skills in dressmaking. Parks was an investigator and secretary for Montgomery, Alabama’s National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She had been trained in civil disobedience and was deeply committed to ensuring that African Americans were accorded their rights as citizens. Her refusal to move to the back of the city bus on December 1, 1955, was an intentional act, and the dress she was working on at the time is on display at the museum.

Nichols also told guests about Anne Lowe, one of America’s most significant designers, with a career that spanned more than 50 years. She paved the way for other Black and women designers to break glass ceilings, and worked for some of America’s most prominent families, including the Rockefellers, Du Ponts and Vanderbilts. Actress Olivia de Havilland was wearing one of Lowe’s gowns when she won an Oscar in 1947 but Lowe is most famous for designing Jacqueline Bouvier’s wedding gown when Bouvier married future president John F. Kennedy in 1953. While working as a designer, Lowe was sometimes underpaid and never given widespread public recognition, although renowned designers Christian Dior and Edith Head openly acknowledged her talents. Forced to retire when she lost her eyesight, Lowe never lost her ability to dream. One of her beautiful dresses can be seen at the museum.

"When developing an exhibition, you start with an idea or narrative, then you work with all kinds of people—designers, conservators, public relations people—to bring it to life,” Nichols said in an interview for Think magazine in 2018. “All these years later, that process still excites me." The CWRU alumna is currently preparing a dress and fashion exhibition which will open in 2027.

The Museum

Guests of the African American Association of CWRU’s Weekend in Washington, D.C. arrived eagerly Saturday morning at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). The Smithsonian institution was established by an act of Congress in 2003 and has welcomed 8.9 million visitors since it opened to the public on Sept. 24, 2016. The collection documents how American values such as resilience, optimism and ingenuity are reflected in the African American experience. And in the words of Founding Director Lonnie G. Bunch III, “it is a museum for all Americans.”

Attendees spent hours on the first floor, reliving the somber journey of their forefathers through slavery and injustice, and through civil rights as they challenged the nation to live up to its ideals of freedom and equality—a challenge which continues today. Upper levels of the museum were lighter, chronicling the role of African American institutions in serving their communities and highlighting gifted athletes and visual, performing, and other artists, whose visibility both inspire and fuel the quest for social change.

“Our country was built by slaves and the museum really puts that into context by giving us a glimpse of their lives,” said AAAA’s Immediate Past President Vera Perkins Hughes, who found her third visit to the museum to be just as exciting as when it first opened. “It also provides perspective to how African Americans have prevailed, despite the challenges, and managed to accomplish great things. It’s very powerful.”

On Saturday evening, the fellowship continued over dinner at Busboys and Poets, “a place to feed your mind, body, and soul,” and Georgia Brown’s, the elegant Black-owned restaurant that features soul food with a twist.

“I was moving table to table during dinner and heard someone say ‘even though we got old, our conversation just picks up right where it left off,’” Perkins Hughes recalled with a smile. “That’s what made the trip so special—the connections.”

The Other Madisons

“Always remember: You’re a Madison. You come from African slaves and a president.”

Bettye Kearse has always known her history, thanks to that phrase, which was passed down through generations of oral historians, along with a box of family memorabilia. As the latest in a long line of griots and griottes, Kearse shared her story with fellow CWRU alumni in an interview with Karen F. Kaler and through a presentation of her 2022 TEDx Talk, “I AM.”

Kearse had mixed feelings when, in 1990, her mother tasked her with writing the family story. Yet she embarked on a 30-year journey, trying to reconcile the pride of being descended from an American president with her anger at the abuses suffered by her ancestors. It infuriated her that her great-great-great-great-great-grandmother Coreen, an enslaved cook in the Madison household, had been raped by James Madison, Jr., and their son Jim sold away.

Kearse’s travels took her to her ancestral Ghana, Portugal, where the transatlantic slave trade had begun, and across the United States. In addition to being a family narrative, The Other Madisons: The Lost History of a President's Black Family (2020), is a tribute to the millions of African Americans silenced by an incomplete recorded history.

She encouraged attendees of her talk to start an oral history tradition with their own families, involving their children in selecting items for a treasure box, and fostering in them their own sense of “I am”, or self-belief.

A third-generation doctor, Kearse loved practicing pediatrics in inner-city Boston, but was dismayed that many of her patients, especially Black teenage boys, believed the lie that nothing awaited them but jail or an early grave. Like Martin Luther King Jr., Kearse has a dream that one day people will not be judged by the color of their skin—even if the judgment is coming from within. Through her book and speaking appearances, she hopes to show that our enslaved ancestors were remarkable people with a sense of their own humanity, who had bequeathed us innumerable gifts, including a strong sense of self. “I am, I am, I am!” Kearse had the audience shout at the end of her presentation. Her response? “Yes, you are!”

Reflections

It was a difficult decision for me to make the excursion to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in March, but I felt this might be my only opportunity. It was also a chance for me to reunite with friends that I hadn’t seen in a very long time. I sent a message to one of those friends, along with the lyrics to Donny Hathaway’s song, “For All We Know,” confirming that this could be the last time we saw each other, and this trip was necessary.

Music was the foundation for my entire college experience. It was in the fabric of the African American experience at CWRU. I look back on the mornings walking through the alley to an 8 a.m. class and stopping by the Student Union to get a cup of hot chocolate—greeting others who also had the good fortune of having an early class on the Case side of campus—and putting a quarter in the jukebox to hear the Beatles hit, “Hey Jude,” which came to be known as the freshman anthem that fall of 1968.

I recall sitting in Clark Towers, listening to Edgar Winter’s song “Frankenstein” blasted over speakers that were three feet tall, cranking up the bass as high as it would go. I want you to know I have significant hearing loss from just that kind of craziness.

Do you remember Spring Break, on blankets on the lawn in front of Sherman House, playing cards, drinking wine, and listening to music that wafted out of several dorm room windows? We took group pictures, threw frisbees, and just enjoyed the warm breezes and the smell of blossoms.

Do you remember the Roberta Flack concert in the CWRU gymnasium? The sistas prepared “soul food” dishes, and after the performance, Roberta Flack came back to the dorm to partake in the feast and socialize. I can’t begin to tell you how excited we all were that she was so down-to-earth and authentic. She was involved in the movement, and her music reflected the plight of the Black Man in America.

In the car on Saturday on the way to the NMAAHC last month, we listened to a reproduction of a 70’s CWRU African American Gospel Choir concert. The choir was under the direction of Ms. Irene Datcher, who was a task master who believed in excellence. Some rehearsals we got it just right, and the blending of chords and voices invited the Holy Spirit into the room. I got chills just hearing Irene’s melodious voice and her magnificent range—the same chills audience members got on Sunday morning when Irene sang the Black National Anthem to open the breakfast program at which Bettye Kearse spoke.

Do you remember going to Leo’s Casino on Euclid Avenue, in the lounge of the Old Quad Hall Hotel? We piled into the available cars on campus and made our way to Leo’s on many occasions. It was an intimate club, with seating for about 700. Sometimes, we sat so close to the stage that performers’ perspiration would drip down on us, and we would scream with excitement. Leo’s had two shows a night and sometimes three on weekends (Case Western Reserve Encyclopedia of Cleveland History). We were entertained by the greatest of all time for $6 and a two-drink minimum per show. If you were under 21, you were given a Hawaiian lei to wear, signifying that all you would be drinking was Hawaiian Punch. We saw Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Jackie Wilson, Marvin Gaye, Ray Charles, Dionne Warwick, the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, Little Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, and Otis Redding, just to name a few. We also attended performances at downtown theaters, where we saw Isaac Hayes, Jerry Butler, Nancy Wilson, and James Brown. Speaking of James Brown, if you didn’t have some James Brown at your party, you didn’t have a party.

On Saturday afternoon, exhausted from the physical and emotional strain of walking the first level of the NMAAHC, we returned home to rest and enjoy more music—this time the music videos of War, Dionne Warwick, the Dramatics, and Bloodstone. Remember their tunes, “Natural High” and “We Go A Long Way Back”? Yes, music is associated with my most cherished memories, and, as The Dells put it,

“the love we had stays on my mind.”

Written by Joannie Brooks Parker (FSM ‘72, GRS ‘74)