The 1965 CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA TOUR OF THE USSR was a major musical tour by the CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA to the SOVIET UNION in April-May 1965, under the directorship of GEORGE SZELL. The trip was part of the State Department’s cultural diplomacy program that President Dwight D. Eisenhower first initiated in 1959 and it was hailed by TIME magazine as “one of the biggest successes in the history of the cultural exchange program.” In his notes on the trip, Cleveland Orchestra manager A. Beverly Barksdale went even further, stating that the tour was “the most important of its kind in the history of international relations.” It came amid the chilliest days of the Cold War, as the war in Vietnam was escalating. Indeed, if one were to view CYRUS EATON’s initiatives as the “political wing” of Cleveland-based détente efforts, then the orchestra’s visit was a major part of the “cultural wing.” As Barksdale wrote, the orchestra “became, under the sponsorship of our Department of State, a collective representative, with music as its public speech. The individuals became 123 envoys of the American way of life. Musically and personally, it won friends wherever it went.” The orchestra visited six major Soviet cities – Moscow, Kiev, Tbilisi, Yerevan, Sochi, and Leningrad (St. Petersburg) – with stops in a handful of other smaller locales, such as Mtskheta and Etchmaidzin.

The orchestra’s Soviet tour had been “three years in the making” according to Barksdale. However, its history of relations with Russia went back even further. In 1935, the orchestra, under conductorship of ARTUR RODZINSKI, presented the US premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District at SEVERANCE HALL. Moreover, its first conductor, NIKOLAI SOKOLOFF, was an immigrant from RUSSIA. Szell hoped to begin the Soviet tour as early as 1964, but the State Department chose to sponsor the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra’s 11-week tour of Europe and the Near East instead.

When the orchestra finally did travel to the Soviet Union in mid-April 1965, they found the trip to be well-worth the wait. In addition to being a significant moment in U.S.-Soviet cultural relations, the orchestra’s tour represented many “firsts.” It was the very first time that any American orchestra had performed in the USSR’s Caucasus region. No American orchestra had ever played in Tbilisi, Yerevan, or Sochi before the 1965 trip. The tour also marked the very first time that an American orchestra attended Soviet May Day festivities, with the Cleveland musicians treated as honorary guests at the May Day celebrations in Tbilisi. Stretching from April 14 to May 20, the 1965 tour was also the longest made by any American orchestra to the Soviet Union. In the subsequent European leg of the tour, it also marked the first time in over 30 years that an American orchestra had performed in Czechoslovakia, and the first to perform in Bratislava.

The orchestra did not know what to expect from their Soviet tour, as the itinerary was decided just days before their departure from CLEVELAND-HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT. Most unexpected for Szell and the others were the scheduled southern venues of Tbilisi, Yerevan, and Sochi. Arriving in Moscow on April 14, the orchestra received a warm reception from the entire Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as from officials representing Goskontsert, the Soviet Culture Ministry, and “all the leading [Soviet] conductors, composers, critics and musicologists” at Spaso House, the residence of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. The meeting went on much longer than anticipated and discussions among musicians from the two sides went on well into the evening. When the Moscow musicians discovered that the dress clothes of their Cleveland counterparts had not yet arrived from London, they “immediately offered their dress clothes and went to great pains to find the proper sizes,” according to Barksdale. U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Foy D. Kohler, and his wife Phyllis told Szell and the orchestra that it was “largest and warmest” Soviet reception that they had ever seen in Moscow. “I don’t care if they stay until midnight or three in the morning,” Mrs. Kohler told the orchestra.

The orchestra stayed in Moscow for a week, visiting the city’s major tourist sites, including St. Basil’s and the Kremlin, and catching rehearsals for the May Day and Victory Day parades on Red Square. At the Bolshoi Theatre, they delighted audiences with performances of works by Berlioz, Schubert, Mozart, and Beethoven. Notably, the second Moscow concert was attended by Anastas Mikoyan and his family, helping to further “break the ice” for the orchestra’s reception in the Soviet capital. The orchestra was delighted to see the Soviet Armenian statesman, but it was not Mikoyan’s first “Cleveland encounter.” He had earlier visited the Forest City in January 1959, where he was guest of Cyrus Eaton. Emotionally moved by the TERMINAL TOWER (which reminded him of the tower at Moscow State University), Mikoyan famously presented Eaton with a gift of a Russian troika on that trip.

Moving south from Moscow, the orchestra flew to Kiev, the capital of Soviet Ukraine. They found the UKRAINIANS to be “proud of their heritage and their own identity” and many in the orchestra were actually surprised by the distinctiveness of the Ukrainian language in relation to Russian. “In fact,” recalled Barksdale, “our own interpreters had to rely upon local interpreters for our guided tours and for certain other things.” At Kiev’s Palace of Culture, Ukrainian audiences were treated to a mix of Beethoven, Bartók, Mozart, and Herbert Elwell. The inclusion of the latter composer, an American and Cleveland native, apparently ruffled some feathers among the musicians who questioned Szell’s “generally lightweight selection of American works.” It was “the only sour note of the tour,” as Time magazine noted.

After the concerts in both Kiev and Moscow, the orchestra’s musicians “adjourned to the youth cafés to sit in on jam sessions with the local hipsters” at a time when the remaining embers of Nikita Khrushchev’s Thaw had yet to be extinguished by Brezhnevian conservatism. When not performing, the orchestra especially enjoyed a local tour of Kiev, which involved stops at the St. Sophia Cathedral, the “gruesome” Kiev catacombs, and the old city gate, which reminded the orchestra of “Moussorgsky and his ‘Palace at an Exhibition’.”

From Ukraine, the orchestra traveled further south, deep into the Caucasus region, a part of the Soviet Union where no American orchestra had ever performed before. “We were not far from Turkey or from Iran,” Barksdale recalled. “We found a wholly different kind of people from what we had found in either Moscow or Kiev.” In Tbilisi, capital of Soviet Georgia, the orchestra received a warm welcome from the GEORGIAN authorities. Observing the city’s annual May Day Parade from the windows at the Hotel Tbilisi, they also received cheers from local Tbilisians. At the time of the orchestra’s arrival, preparations for the parade “were almost complete,” with women planting flowers and “enlarged likenesses of Mikoyan, Kosygin, Brezhnev, and Georgian political figures dominating the eye.”

Earlier, while the orchestra was still in Kiev, the Georgian authorities had extended an invitation to them to perform an evening May Day concert. In response, the orchestra members voted to give up their free day and accept the Georgian invite. It was to be their first concert in Soviet Georgia, performed at Tbilisi’s National Opera Theater, a neo-Moorish structure, the theater was completed in 1851, under the patronage of Prince Mikhail Vorontsov, the Tsar’s governor of the Caucasus. For their performances in Georgia, Barksdale recalled that the Georgian government ordered the construction of a platform over the orchestra pit specifically to accommodate the visiting American orchestra. The stage, he remembered, was “enclosed in a set from the fourth act of ‘Othello.’”

On the first night, the orchestra delighted a “capacity crowd” that seemed to grow with every evening. Given the limited number of seats, the Georgian authorities provided room for more and more standees with each new concert. The attendance was such that even standing room was not enough. “Crowds which couldn’t get in the hall milled about for blocks,” recounted Barksdale. On the night of the first concert, “every square inch of space in the opera house was occupied and people were often sitting two in one seat,” so much so that Barksdale and Szell worried about what might happen in the case of an emergency. Such an incident occurred when a thunderstorm caused a power outage in the middle of the concert. However, the audience did not panic and waited patiently for the matter to be promptly remedied.

Afterwards, the jovial and gregarious Georgians treated the orchestra to a traditional Georgian keipi (i.e., festive feast) at a restaurant on David Mountain (Mount Mtatsminda), overlooking Tbilisi and the Kura River. The view reminded Barksdale of STOUFFER’S Top of the Town in Cleveland, and in his notes, he even dubbed it the “Top of the Town of the Caucasus.” As recounted by Time, the orchestra was “serenaded by Georgian folk singers” at this “sumptuous banquet” and the Georgians were quick to set aside Cold War political differences in favor of cultural celebration. “As one Tbilisian put it, inviting the musicians to join him in a drink: ‘Viet Nam, nyet! But you, yes!’,” the magazine wrote. Orchestra members also explored Tbilisi’s colorful bazaars, and, outside Tbilisi, the orchestra ventured to historical Mtskheta, the former capital of Georgia and one of the republic’s oldest cities. Although disheartened by the decline in attendance at religious services, Barksdale nevertheless noted the Georgians’ tolerance toward religion and was struck by the fact that locals could still worship “without interference” from the atheistic Soviet state.

The orchestra’s next stop on their itinerary was to be the ARMENIAN capital Yerevan, an engagement that may have been encouraged by Mikoyan, given his close ties with Soviet Armenian officials. En route from Georgia to Armenia via bus and automobile, the visiting musicians passed through northwestern Azerbaijan, just north of Armenian-inhabited Nagorno-Karabakh. In Barksdale’s words, “we went over passes of more than eight thousand feet and we saw villages and settlements that could be seen nowhere else except in the National Geographic.” In some of these villages, into which tourists at the time “seldom” ventured, “houses were made of mud, and the only fuel [were] the bricks they made of dung and straw.”

Arriving across the border into Soviet Armenia, the orchestra was greeted by members of the Armenian Philharmonic Society with a significant reception at Lake Sevan. At a restaurant overlooking the lake, they admired its turquoise waters and feasted on its famed ishkhan (“prince”) trout, “served cold with a light dressing and much Armenian cognac.” Like British Prime Minister Winston Churchill before them, the orchestra was especially fond of the cognac, which they hailed as “the best cognac that we tasted in Eastern Europe.” The feast was peppered by several toasts and the visiting musicians found the Armenians to be just as “wonderfully warm and hearty” as the Georgians. They even engaged in a “jam session” with Armenian duduk players, and later decided to purchase duduks of their own in Yerevan.

From Sevan, the orchestra traveled to Yerevan, where they performed at the Yerevan Opera Theatre to a Beatles-like reception. “We had some of our most enthusiastic audiences in Yerevan,” Barksdale recalled. As Time put it, “[In] Yerevan, hundreds of fans attempted to batter their way into the concert hall, and heavy police reinforcements had to be rushed in to quell the riot. Pianist John Browning, 31, whose brilliant interpretation of Barber's Concerto for Piano and Orchestra was one of the critical highlights of the tour, attracted an avid following of young girls, who stormed the stage crying ‘John, John . . . oh, John!’ When Violinist Gino Raffaelli was spotted on the street, the volatile Armenians demanded an impromptu sidewalk recital. He complied.”

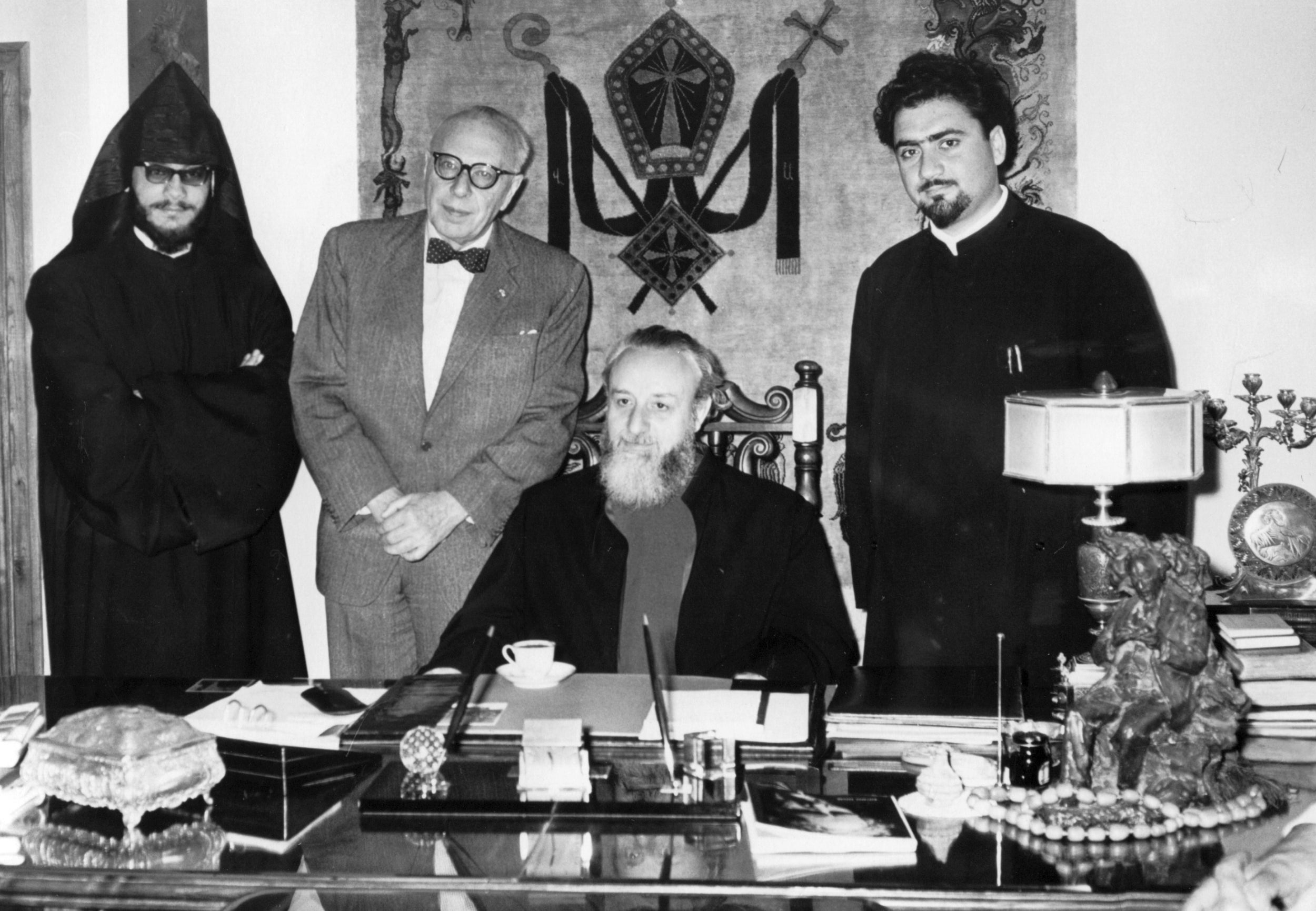

Outside Yerevan, the orchestra also visited Etchmaidzin, the “Vatican” of the Armenian Church. It was there that Szell met with the Armenian Orthodox Patriarch (Catholicos) Vazgen I, arriving an hour before the rest of the orchestra. At the private meeting, Vazgen gave the Cleveland conductor a personal tour of the grounds of Etchmaidzin Cathedral, before the orchestra arrived to rejoin him. The Catholicos addressed the visitors in “good English,” gave them his blessing, and sent “his warmest greetings to the people of America.” “I am glad men of great art of the United States have come to Armenia,” Vazgen said. “There must be more visits like this between Armenia and the United States. Through music, people can love each other more. In my heart I have a joyous feeling for the United States. Not only for Armenians there, but for all Americans.” Back in Yerevan, the orchestra toured the renowned Matenadaran, where they examined historical Armenian illuminated manuscripts.

Departing the Armenian capital, the orchestra traveled north to the Black Sea resort city of Sochi, in the shadow of the Greater Caucasus Mountains. Better known in recent times for hosting the 2014 Winter Olympics, the spa town and its sanatoriums greatly impressed the visiting orchestra. Amid the semi-tropical scenery and Hellenistic architecture, the visiting musicians stood in awe of the Greater Caucasus. “Some of these peaks are higher than anything in the Alps,” recalled Barksdale. “The view was breathtaking.” The orchestra arrived just in time for the city’s Victory Day (May 9) celebrations, marking the 20th anniversary of the end of WORLD WAR II and honoring Soviet veterans. Military pomp and pageantry were on full display among the palm trees and seaside landscape. Soviet speakers invoked Cold War rhetoric condemning “American militarism” abroad. As Barksdale recounted, “some of our men [who knew Russian] could understand what was being said, and one of our interpreters asked if we did. We replied that it was probably something anti-American, and he laughingly said: ‘Yes. They are simply calling you war-mongers again.’” In addition to such moments of levity, the orchestra enjoyed a warm welcome at their performances at Sochi’s Winter Theatre.

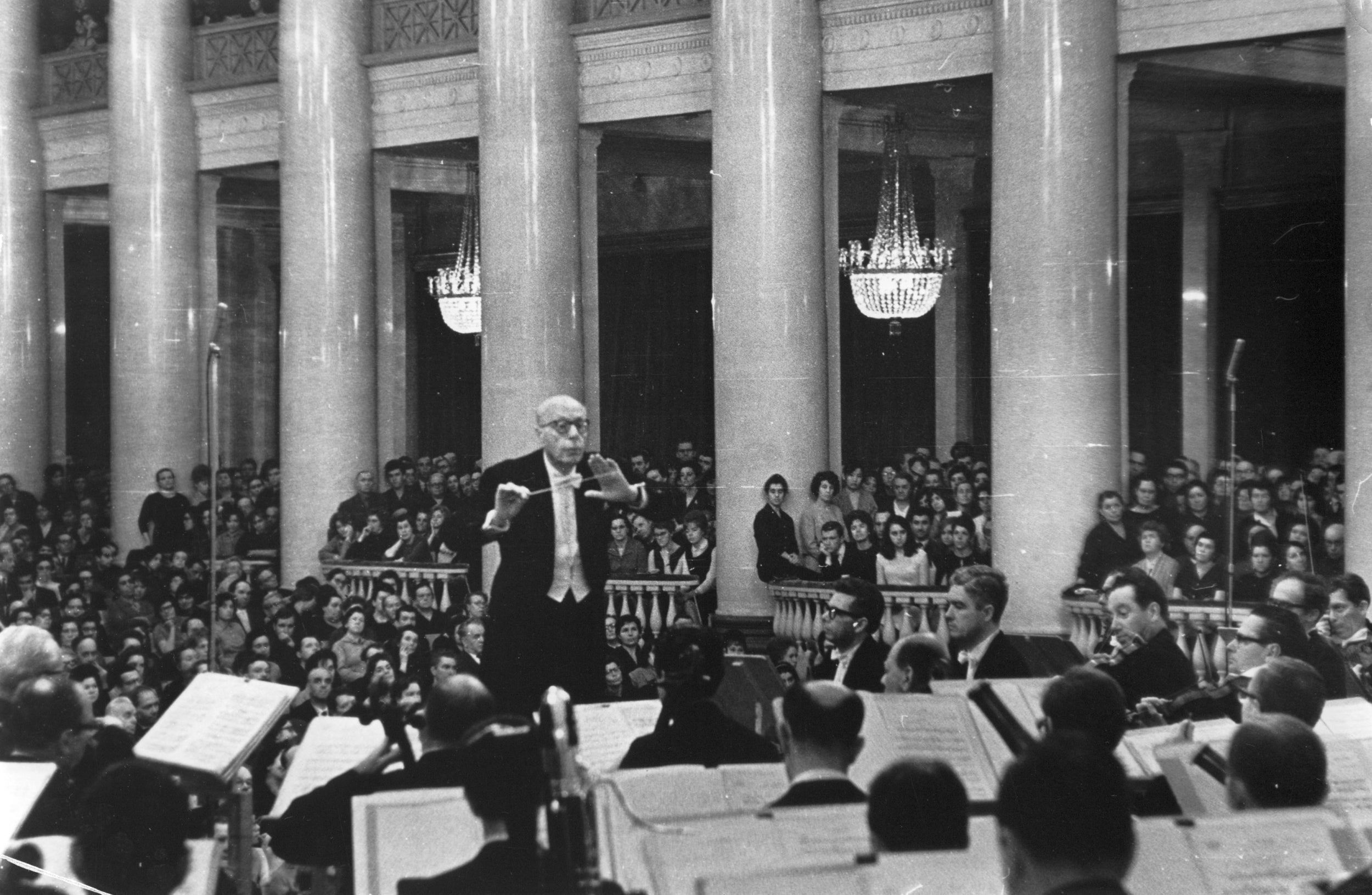

Traveling further north, the orchestra arrived in Leningrad (today St. Petersburg). Although visibly damaged by the war, the city was rebuilding, and Szell and his musicians were impressed by the post-war reconstruction efforts. "The capital of Peter the Great is as beautiful as we had heard it would be,” recalled Barksdale. In Leningrad, the orchestra performed at the Leningrad Philharmonia Bolshoi Hall to a rousing reception. “It was a glorious experience to play here, both visually and aurally, in what is truly one of the great halls of the world,” noted Barksdale, who also noted the meticulous effort by the Philharmonia’s musicians to save the hall’s crystal chandeliers from the Nazi onslaught. In earlier notes, Barksdale went even further and praised the hall as “by far the best hall in all of Russia and, as I look back over it, the best hall we played in anywhere on the tour [including Western Europe].” As in Tbilisi, Yerevan, and elsewhere, the orchestra was greeted by massive crowds of excited Leningraders packing the hall. When not performing in Leningrad, orchestra members were awed by the sites in and around the city, including the Hermitage (especially the Treasure Gallery), Peterhof Palace, and the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoye Selo (Pushkin).

The orchestra’s Soviet tour was a major success. However, as the orchestra departed the Soviet Union for their next stop, Finland, its members were somewhat sad to leave the enthusiastic Soviets. As Barksdale recalled, “after the enormous enthusiasm of the Soviet audiences, we had prepared ourselves for a letdown in Scandinavia, where there is supposed to be no less enjoyment but a great deal more reserve.” However, the subsequent Helsinki tour was to prove this concern unfounded. The orchestra’s Helsinki performance of Jean Sibelius’ 7th Symphony was met with a rousing reception by the supposedly reticent FINNS. “A wholly new type of ovation developed at that point,” recalled Barksdale, “and continued throughout, after encores had been played at the close of the program.” In attendance were three of Sibelius’ daughters, seated just behind the wives of Szell and Barksdale. The shuffling of their feet against the auditorium’s wood floor soon inspired the entire audience to do the same in imitation. “The result was a magnificent din,” remembered Barksdale.

From here, the orchestra went on to enjoy a successful performance in Stockholm and an equally successful tour throughout the Eastern bloc and Western Europe, delivering performances in Warsaw, Hamburg, Paris, Bergen, Berlin, Prague, Bratislava, Vienna, London, and finally Amsterdam. The orchestra’s tour was a major success and a stunning achievement in Cold War cultural diplomacy. It highlighted that, despite differences in the political realm, a common love of music could draw together both sides, forging a common musical dialogue between East and West.

Pietro A. Shakarian

American University of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia

With special thanks to Andria Hoy of the Cleveland Orchestra Archives for her input and assistance.

The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

“Triumph Abroad.” Time, May 28, 1965.

Barksdale, A. Beverly. A Report on the Tour of the Soviet Union and Western Europe Made by the Cleveland Orchestra Under the Auspices of the U.S. Department of State, April 13–June 26, 1965. Cleveland: Members of the Musical Arts Association and Friends of the Cleveland Orchestra, 1965.

Koppes, Clayton. “The Real Ambassadors? The Cleveland Orchestra Tours the Soviet Union, 1965.” In Music, Art and Diplomacy East-West Cultural Interactions and the Cold War, ed. Simo Mikkonen and Pekka Suutari (London: Routledge, 2016), 69-86.

Rosenberg, Donald. Second to None: The Cleveland Orchestra Story. Cleveland: Gray & Company, 2000.