Beyond the Silence was written by Ellen H. Brown for CWRU Magazine's Summer 2002 issue. The full article is also available in PDF format.

For readability, this article uses "gay" synonymously with "gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT)."

From a distance, they looked like any other swarm of college students, celebrating the first heat of spring. Sprawled out on the grassy oval outside Kelvin Smith Library. Most clad in shorts and T-shirts. Many barefoot. Some chatting. Playing Frisbee. Or paging through textbooks.

The only sign this group was "different" was the flier announcing their event: Live Homosexual Acts.

What are live homosexual acts?

Students reading and talking and flinging Frisbees. Students laughing and embracing and worshipping the sun.

If that answer surprises you, CWRU undergraduate Jean Broughton, for one, is pleased. Ms. Broughton, who quits a Frisbee match to be interviewed, says the name of the event, staged at colleges throughout the country, is intended to be provocative. Part of its premise is to obliterate the myth that "being gay is all about sex," she says. "The fact is that gay people do what everybody else does. We read. We hang out. We talk. We go to class. We do schoolwork."

Live Homosexual Acts was sponsored by Spectrum, the University-supported undergraduate student group for people who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) and their straight allies. Ms. Broughton, the driving force behind the event, had almost called it off. She was fearful that few supporters would show up and concerned that the group would face harassment from fellow students. But she's glad she persevered, thrilled that so many people—thirty—attended, and that others didn't hassle them.

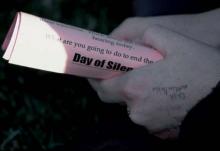

Ms. Broughton admits that the success of Live Homosexual Acts was a rarity on campus, where attendance at GLBT events is often scant. A week earlier, for example, Spectrum sponsored the annual Day of Silence, an event that promotes awareness of anti-gay harassment and discrimination. On that day, GLBT students and their supporters don't talk. Instead, they hand out cards that say, in part, "My deliberate silence echoes that silence which is caused by harassment, prejudice and discrimination. I believe that ending the silence is the first step toward fighting these injustices." Only four students turned up at the end of the day for the Break the Silence rally, a decompression session for participants.

By all accounts, very few gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students, faculty, and staff are "out" and visible on campus. This applies particularly to women, many of whom declined to be interviewed for this article or requested to remain anonymous. Many describe the environment as unsafe and isolating for people who are GLBT. And some suggest that a "don't ask, don't tell" mentality exists, which helps reinforce the impression that there isn't a gay presence at CWRU.

In September 2001, the CWRU President's Commission on Undergraduate Education and Life reported there are "signs that the campus environment is unsupportive of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students. Events sponsored by gay and lesbian students are, for example, routinely greeted with bigoted graffiti on the sidewalks." Examples of the graffiti have included "Hitler Was Right," "God Hates Fags," and "Die Fags."

The commission advised CWRU to increase the diversity of the undergraduate student body, in such areas as race and ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. The report also encouraged the Office of Housing and Residence Life to continue training resident advisors to be aware of GLBT issues, and suggested that the University follow the lead of other campuses that have implemented measures to address this problem. Noting that other institutions have offices to provide programs for people who are GLBT, the report recommended that the University create a liaison officer position for GLBT issues.

Though it's impossible to know how many people on campus are GLBT, most studies suggest that 10 percent of a population is typically gay, which means that about 1,500 faculty, staff, and students at CWRU could fit that category.

Jes Sellers, the director of University Counseling Services, believes there are a significant number of people on campus who are GLBT, but that few are out. Dr. Sellers, who co-founded the Cleveland chapter of PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) with colleague Jane Daroff in 1985, counsels a large number of students who are GLBT. And of the couples he works with, more are gay and lesbian than heterosexual.

When people are asked why they believe so few members of the campus community are out, a jumble of possibilities tumble out:

- The University administration isn't supportive enough of people who are GLBT;

- CWRU is a conservative University in a politically conservative state;

- Certain incidents make the campus appear unsafe or intolerant;

- People who are uncomfortable with their GLBT identity may be hesitant to come out, fearing repercussions.

Though a few people interviewed for this article insist that the campus is homophobic, perhaps Dr. Sellers best captures the sentiments of many GLBT people. "I don't think it's a mean-spirited campus," he says. "It's more of a benignly neglectful atmosphere. It's not what you'd call friendly or supportive; it's tepid."

Undergraduate student Sarah Baker notes that the campus is "friendly enough if you find the right people," but believes the University is reflective of Ohio's mentality—a mentality, she says, that is behind the times. "If a potential student were looking for a campus that is accepting [of people who are GLBT], they wouldn't choose Case," she says.

But what makes CWRU less than accepting, as Ms. Baker suggests? People point to signs of intolerance and hate. Consider these incidents, which occurred on campus:

- When a short-haired woman was walking across campus, a male student hurled these words at her across an open green: "You're a f***ing dyke!"

- Two years ago, a student who lived in a suite adjacent to Spectrum President Paul Valentine placed a poster on his suite's door that said, "Silly faggot, dicks are for chics." Though Mr. Valentine repeatedly removed the poster from the other student's door, he kept replacing it;

- When Sue Pearlmutter, an assistant professor in the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, requested that domestic partners be included in the school's directory, which lists the names, addresses, and phone numbers of faculty and staff and their spouses, her suggestion was ignored until a straight ally insisted on including the names of partners (regardless of whether the couples are heterosexual or homosexual);

- When Karl Hawkins (LAW '02) first arrived on campus, he met in neighboring Little Italy with a few fellow law students. Over drinks, he asked one of them why he chose CWRU's School of Law. His response? "Because there are fewer queers and fags at this law school than at other schools."

While such incidents are not unique to CWRU, they help shape people's perceptions of the institution.

According to Jane Daroff (SAS '85), a social worker in University Counseling Services, such incidents can also undermine the self-esteem of students who are GLBT or questioning their sexual orientation. Adds Dr. Sellers, "Being called a fag or dyke can impale students who are figuring out who they are."

But the news is not all negative. There are positive stories to relate. For example, last year, during orientation, Jes Sellers noticed a small group of male undergraduates hanging out near Thwing Center, some on skateboards, some on bicycles, two holding hands. "I didn't observe a single person flinch as they walked by [the couple]," he recalls. "It was really amazing that they felt comfortable enough to do that."

Later that year, when undergraduate Fred Bachhuber came out to his fraternity brothers in Sigma Alpha Mu, they thought it was a joke, he recalls. But once they realized Mr. Bachhuber was serious, they were "fine with it," he says, "and I haven't suffered any repercussions."

While many GLBT activities are less than triumphant, others, such as this year's Live Homosexual Acts and the Lavender Ball—an annual spring dance, sponsored by Spectrum, for GLBT folks and straight allies—are, by comparison, grand successes.

At this year's Lavender Ball, the crowd was still sparse at 9 p.m. (attendance eventually topped off at 119) in the Thwing Center ballroom, but no one appeared to mind. "People seem to be loosening up," said one young woman, gesturing toward a few couples and threesomes who'd taken to the dance floor, their bodies shimmying against the spin of the rainbow light show. A few feet away, CWRU undergraduate Kristen Conrad and some female friends were seated at a round table, all volleying balloons. When Ms. Conrad was asked what she thought of this year's Lavender Ball, a serene expression appeared on her face: "There is so much positive energy here tonight," she said, acknowledging that the University isn't the most comfortable place to be out. "I feel very free here. It's a great feeling. The whole thing is like a burst of fresh air."

Around campus, a number of men and women interviewed for this article suggested that pockets of support exist. "I think the level of support depends a lot on where you are in the University," said David O'Malley last spring. Dr. O'Malley (SAS '01) was an assistant director of housing at CWRU who left in July to become an assistant professor of social work at Cleveland State University. "A lot of it is about leadership and who your dean or VP is and how supportive they are. My division [student affairs] is very welcoming, and I'm very grateful for that. Counseling services and campus ministries are also very supportive."

Karl Hawkins, who graduated from the law school in May, echoes Dr. O'Malley's sentiments. Mr. Hawkins, who was a resident director, offers nothing but praise for members of the residence life staff, who "make a substantial effort to talk about diversity," including issues related to being gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender. The staff's "openness makes it easier for me to be out and for students to come and talk to me," he said last spring. "Residence life has been my savior and safe harbor. Being an RD has been a lot of work, and they expect a lot, but Res Life has been a gift from God for me."

While Ellie Strong, a conservator at Kelvin Smith Library, believes the campus could be more supportive of GLBT students, she's "found it pretty easy to be a lesbian on staff at the library." She adds that she hasn't encountered any barriers or discrimination on the job.

In recent times, the University, as an institution, has shown signs of support. In 1989, CWRU added sexual orientation to its nondiscrimination policy, which states, in part, that the University "does not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, age, sex, color, disability, sexual orientation, or national or ethnic origin." Ten years later, the University decided to offer benefits to domestic partners (both same-sex and opposite-sex) of CWRU employees. Though some people on campus disputed the proposed policy in public forums, the benefits took effect in January 2000. Supported by the Staff Advisory Council, the Faculty Senate, and then-President Agnar Pytte, the policy made healthcare and dental insurance available to domestic partners (DPs).

Earl McLane, CWRU's associate vice-president for human resources, says the move "was part of the University's position as far as diversity is concerned. It was a collaborative effort across the whole University. And it was something whose time had come."

For their part, many GLBT people on campus believe that, after years of reticence and apprehension about how such a policy would be perceived, CWRU agreed under pressure to offer the benefits. Nevertheless, many gay faculty and staff express appreciation for the University's willingness to extend benefits. Among them is Ellie Strong, whose partner has been able to use the University's benefits plan.

Some people, meanwhile, believe the University should make the benefits equal to those available to spouses of University employees. A number of people noted that certain benefits such as tuition waivers and dependent life insurance—which are available to employees at some of CWRU's peer institutions—are not available to domestic partners of University employees.

Mr. McLane says the University is working to make benefits equal. Beginning this fall semester, domestic partners will become eligible for CWRU tuition waivers. And next year, he says, the University will attempt to identify life insurance carriers willing to cover DPs.

When members of the campus community are asked what would make CWRU a friendlier place for people who are gay, the answers flow freely. More services and support. A stronger commitment to educating students—and the entire campus community—about GLBT issues. More faculty members who are out and supportive of students. And a more powerful pledge on the part of the University administration to making CWRU a more accepting place, in general. (To learn more about the University's perspective, "A More Welcoming Place.")

Undergraduate Fred Bachhuber, like many of the students interviewed, insists that providing a "safe space," where GLBT students could gather, is key. He also advocates the creation of a Safe Zone program, in which faculty, staff, and students (homosexual and heterosexual) offer support to GLBT students, some of whom are questioning their sexual orientation or working through the coming-out process.

CWRU undergraduate students James Rodgers III and Edward Payabyab, on the other hand, are lobbying for the University to open a GLBT center, staffed with a person who would coordinate programming and offer guidance. The University talks about "being Ivy-League caliber," says Mr. Rodgers, "but if they want to be considered Ivy League, they need to develop programs that put them in that league."

Many contend the campus community needs to become better educated on issues of diversity, in general, and GLBT issues, in particular. The University, some suggest, should launch a comprehensive, ongoing effort to introduce members of the campus community to people from different cultures and lifestyles. "Part of what an education is all about is to learn about other people, to learn to be accepting and realize that people are different," says Jane Daroff. "This campus doesn't do enough to make that happen."

Kent Smith, director of Multicultural Affairs at CWRU, says that, in his experience, "Students here are above and beyond others in terms of maturity. But our campus isn't the most conducive to exposing our students to different cultures and lifestyles. Students, for the most part, operate within their own sphere and don't reach beyond their comfort zone, and that's too bad."

Most people interviewed insist that CWRU should take a stronger stand when anti-gay incidents occur.

Says staff member Ellie Strong: "I think it would be helpful if, when there are derogatory chalkings or harassing comments made, the University would take a stand and say, 'This is un-acceptable' or 'We do not want this type of behavior on our campus.' That would go a long way in making people here feel supported, especially students, who are the ones who really need that support."

Shan Mohammed (MED '97) is one of several people who believe the University has an important role to play. A clinical instructor in the School of Medicine, Dr. Mohammed says, "I think the University's role should be to create an environment in which people can be who they are and to create a community in which people can be challenged and supported, and can grow and be nourished. It takes commitment and energy, but it makes the University a greater place for everyone."

Associate Editor Ellen Brown thanks the people willing to be interviewed for this article. Though many of their names were not included, all their perspectives helped shape the story. Photography by Janine Bentivegna

It's 1:30 on an April afternoon, and Glenn Nicholls has just returned to his office after breaking bread with incoming President Edward Hundert and a group of CWRU students. During the informal luncheon, explains the vice-president for Student Affairs, an officer from Spectrum talked about what the University could do to make the campus more welcoming for GLBT students. The student, he says, described the environment as "pretty good" but claimed it would be friendlier if GLBT students were provided with a safe space and a liaison. The response of President Hundert "was very affirming, just as you'd expect," says Mr. Nicholls.

While Mr. Nicholls concedes that the campus isn't especially "gay friendly," he insists that it isn't a hostile place, either, pointing to the University's anti-discrimination policy and domestic partner benefits as signposts of its support. Still, Mr. Nicholls says that CWRU could listen more attentively to students' concerns. "It makes sense," he says, to assign a liaison from his staff to help GLBT students. And it makes sense to create a Safe Zone program, which would serve as a reminder of the University's support, he adds. In programs at some colleges and universities, faculty, staff, and students are trained to offer support to GLBT students. Given the concerns raised by students and the recommendations of the CWRU President's Commission on Undergraduate Education and Life, he believes both of these notions merit an examination this academic year.

Mr. Nicholls notes that a number of staff members in student affairs have already placed "safe space" posters on their doors, announcing that it's a safe place to talk about a variety of topics, including homosexuality. But a Safe Zone program would be more comprehensive.

On a similar note, Mr. Nicholls and Mayo Bulloch (GRS '80, education) support the idea of establishing a place on campus that would provide staff, programming, and advocacy for GLBT students. "It's a group that's isolated and could benefit from having a place" where they could congregate, says Ms. Bulloch, director of educational enhancement programs at CWRU.

She admits that it's difficult to teach students to accept differences in other people "without seeming preachy and turning people off." But she believes it's a crucial endeavor, and one that needs to begin when students come together at freshmen orientation. Orientation, she says, also allows CWRU to discuss academic freedom and freedom of speech.

A campaign called Share the Vision, launched in 1990, has also played an important role in educating students, according to Ms. Bulloch, chair of the Share the Vision committee. Originally part of an orientation program introducing students to values embraced by the University, such as diversity and mutual respect, Share the Vision works toward building a humane campus community.

Four years ago, the committee began sponsoring programs throughout the school year, as well as during orientation. One such event, a candlelight vigil in memory of Matthew Shepard, was fueled by a nationwide reaction to the brutal murder of the gay college student in Wyoming. The turnout for the vigil was high. "People talked very personally about how they had been touched by his death," says Ms. Bulloch. "I think because he [Matthew] was their age, it really captured the spirit of the student body." In recent years, the committee has planned other GLBT-related events, including a forum focusing on law, religion, and homosexuality.

The residence halls provide another venue for discussing sensitive topics, according to Sue Nickel-Schindewolf, associate director for residence life. The Office of Housing and Residence Life does its best, she says, to integrate GLBT-related perspectives into programs. Sometimes, though, those discussions take another shape, she notes, referring to a recent incident in which students defaced a poster with hateful speech, some homophobic. Oftentimes, the residence hall assembles students to discuss such matters. "You can't necessarily change people's ideas," she says, "but we have a responsibility to challenge hateful speech."

As for the hateful chalkings that appear on the pavement, Mr. Nicholls says, "We try to get someone out there to remove them as quickly as possible." But, he adds, the University is also obligated to protect free speech, even if that speech is hateful. And striking that balance, he concedes, can be difficult.

I have been on many college campuses in Ohio as well as in other states and have come in contact with many gay people on those campuses. However, the one thing that is noted on this campus is the lack of openness of gays. Even though there is an active gay group on campus, the lack of participation of gay students on campus vs. active member gay students within the organization is astounding. For some reason, there seems to be a personal suppression that does not seem evident elsewhere.

—Excerpt from an editorial by John T. in the October 9, 1973, edition of The Observer, the Case student newspaper.

Through the years, gay and lesbian life on campus has represented a rich but often quiet part of the university's culture. In the early 1970s, the Gay Activist Alliance was established at Case, as the gay liberation movement gained momentum across the country following the Stonewall Riots in 1969. In June of that year, police raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in New York's Greenwich Village, sparking a violent uprising. Though such tavern raids were not uncommon in those days, patrons rarely resisted. But on that night in June, the crowds in the Stonewall Inn fought back, and violence erupted in the street.

It was also in this period, in 1973, that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its new diagnostic manual of mental disorders.

The first sanctioned group on campus devoted to gay people, the Gay Activist Alliance, was both an activist and social organization sponsoring seminars, dances, and other events and publishing a newsletter called theLavender Pages.

Composed of students, faculty, staff, and members of the Cleveland community, the group also provided a hotline for gay people. In the early 1970s, numerous articles, editorials, and letters to the editor, which discussed the GAA and its activities, appeared in the Observer. One editorial, which ran on September 15, 1972, stated, in part: "We mark the surfacing of a gay organization at CWRU as a sign of the times that is long overdue. We will support their efforts, as liberating actions for a minority long suppressed and harassed. We hope the students here have the maturity to do the same."

In the late 1970s, the name of the GAA changed to the Gay Student Union, and the late anthropology professor, Charles Callender, served as the faculty advisor for the organization, which met regularly and featured a number of social events, including an annual dance.

Through the years, the group has waxed and waned, depending on the level of student involvement and leadership--as has been the case with other GLBT-oriented groups on campus, including those based in the School of Law, the School of Medicine, the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, and the School of Graduate Studies, some of which are not currently active. And, depending on the students involved, the Gay Student Union took on slightly different forms. In the 1980s, the group also held weekend-long conferences that featured workshops, films, national speakers, and parties. Although the conferences were free for students, very few students attended, possibly for fear of being identified as gay or lesbian. Many of the people who participated in the conference were members of the Greater Cleveland community.

In the 1980s, the Gay Student Union was renamed the Lesbian Gay Student Union to recognize the identity of lesbians. Though the name of the group has changed over the years to become more inclusive (to the Gay Lesbian Bisexual Alliance and Spectrum), its purpose has typically been social, educational, and political.

As an alumna of Case and a former longtime administrator, Patricia Baldwin Kilpatrick possesses a wealth of personal knowledge on university history. When she is asked what the climate was like for people who were lesbian or gay when she was a college student at the Flora Stone Mather College for Women, she lets out a thunderous laugh. "I can tell you that, until 1970, the subject was never mentioned. It was like the military," says Mrs. Kilpatrick (FSM '49; GRS '51, physical education), vice president and university marshal emerita. "Don't ask, don't tell." When she was a college student, she recalls, "There were more rumors than anything else." But if women were athletic or had their hair cut short, people would make derogatory remarks. "Consequently, some people were always on edge."

In the 1970s, when Mrs. Kilpatrick worked with students as a freshman and dormitory advisor, she says students and peer counselors came to talk to her about their feelings, and some admitted to being lesbians. "I was very fortunate in developing, over time, a feeling of openness with kids," she says. "Students felt good about talking to me, and I developed a warm relationship with them."

She remembers one student, in particular, who once came to her in a despondent mood. She and Mrs. Kilpatrick talked at length, and the student revealed she was a lesbian. Through the years, the woman has kept in touch with Mrs. Kilpatrick; and the two have developed a lifelong friendship, she says.

In those days, she notes, "It was so hard because it was something you couldn't talk about with anyone. You'd just expect rejection. Today it's different. People are still bigoted, of course. But at least some people are willing to talk about it."

What follows are accounts from Case alumni who were willing to talk on the record for this story.

Robert Daroff, Jr. (WRC '86, MED '90)

For Rob Daroff, attending Case as an undergraduate and a medical school student was like living in two different worlds. As an undergraduate, "I felt very isolated," recalls Dr. Daroff, now a staff psychiatrist at the San Francisco Veterans Administration Medical Center and the son of Jane Daroff, a social worker in Case's Counseling Services office. "It felt like a big, cold place." As he'd walk across the Case quad, he remembers "feeling isolated and alone and feeling like a marked man, because I was 'out.'" As time went by, he became involved in what was then known as the Lesbian Gay Student Union, where he befriended some students who were a "great support to me."

Another source of support was the anthropology professor, Charles Callender, who served as a mentor to Dr. Daroff and many other students (GLBT and straight). Professor Callender taught a course called the "Anthropology of Sexual Deviancy." Though the title of the class left something to be desired, says Dr. Daroff, with a laugh, the premise of the class was great. Professor Callender, who didn't come out until later in life, would chain smoke in class using a big jar as an ashtray, pacing back and forth "and talking about the variety of sexual expressions through time. He helped us reexamine our assumptions about what's normal and how a culture comes to define deviant behaviors." Over time, Dr. Daroff remembers, "I developed a wonderful relationship with him. He was the ideal professor. He helped me academically and helped me come out and flourish. He was an incredible force in my life."

While the Case double alumnus doesn't remember encountering much overt hostility on campus, he does recall one incident that, he says, "really scared me." At the time, he was volunteering on a local gay hotline, and he'd placed an ad in the Observer informing students that he'd be staffing the hotline on a specific time and day. "There was one student who called several times and seemed to be having a hard time coming out," he recalls. When the student asked Dr. Daroff to meet him on campus to continue their conversation, he agreed. But the man never showed up at the designated time and place. "So I figured he got freaked out and didn't show up," Dr. Daroff says. When the man called the hotline the next week and told Dr. Daroff, "I saw you there, you f***ing faggot. I know who you are now," Dr. Daroff remembers being "very freaked out. Quite paranoid that that guy was going to hurt me."

When Dr. Daroff continued on to the School of Medicine, however, he remembers his experience being very different, recalling that the "medical school was like an island unto itself, and it felt very safe there." In his first year, there were twelve other GLBT students in his class who were out, so he and a fellow student launched and became active in the Case chapter of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered People in Medicine. Though some people wouldn't associate with Dr. Daroff because he was gay and out, "We were certainly tolerated, and I felt very safe and supported," he says. "We had a good quorum [of GLBT students] in our class."

Today, as an assistant clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California at San Francisco, Dr. Daroff serves as a mentor for gay students. He stated that "I know that kind of support can make such a difference in students' lives, even in San Francisco, where being gay isn't that big of a deal."

Timothy Downing (LAW '88)

In his first semester of law school at Case, Tim Downing recalls trying his best to compartmentalize his life and rarely socializing with other students. "Law school is hard enough, especially in the first year," says Mr. Downing, now a partner with the law firm of Ulmer and Berne, LLP in Cleveland. Back then, he was afraid to be out because he wasn't confident about who he was. Fearful that his sexual orientation would affect his grades and how people--particularly faculty members—would perceive him, he chose to stay "in."

But by the second semester, Mr. Downing began venturing out to gay clubs on weekends, eventually realizing that some of the people he saw at the clubs were also law school students.

"I realized I wasn't alone," he says. Slowly but steadily, he began talking with and befriending some of those people. "We had a sort of secret club going," he says, laughing, noting that "it helped to have a group of students to hang out with."

But the group was closeted, for the most part. Many, including Mr. Downing, were afraid of how faculty members and future employers would react if they knew the students were GLBT.

Mr. Downing acknowledges that some of his fears stemmed from being uncomfortable about being gay. "Because," he admits, "the more comfortable you are with who you are and being gay, the more willing you are to be out."

As time went by, Mr. Downing became more and more confident about who he was, he began "taking baby steps," he recalls. "I didn't lie about where I'd been over the weekend, if it came up."

In his second year of law school when he met Kenneth Press (WRC '84), who would later become his life partner, he accepted who he was and realized that he wanted to live an open, honest life. "It didn't cause me to wave a rainbow flag through the law school," he says. "But I pledged to myself that I would be true to myself and honest about who I am."

When asked what the climate was like for students who were GLBT, he sighs. "In the mid-eighties, I wouldn't say the climate here was particularly hostile, but it also wasn't very welcoming," he says, noting that his assessment refers only to the law school. "There was a sort of 'don't ask, don't tell' policy." While he heard whispers and rumors about certain faculty and staff who were GLBT, he explains, no one talked about "so and so in a particular department who was openly gay."

Barry Rice (CWR '91)

When Barry Rice reflects on his years at Case, he remembers them being a catalyst for his growth, both personally and academically. "It seemed like the university was a pretty easy place to be out," says the formerObserver editor, who is now a professor and acting chair of the journalism department at Columbia College Chicago. He recalls, "It was generally an accepting place."

That was particularly the case in the Department of Theater Arts, remembers Mr. Rice, who came out in his junior year after switching his major from biomedical engineering to theater arts: "It was a pretty open crowd that I hung out with."

Mr. Rice also found the Office of Counseling Services and the Office of Housing and Residence Life to be supportive. When he first came out, he remembers meeting with a therapist in the counseling center who was helpful, he says, unsuccessfully searching his memory for her name. The residence life staff was "very progressive," he remembers. Mr. Rice, who served as a resident assistant during his junior and senior years, recalls that there was a "very progressive diversity-training program for resident assistants" and that the staff tried to sensitize students to many different issues in residence life programming, including GLBT-related concerns.

"I had a positive experience at CWRU," he says. "I had good faculty members. I had a good social experience. I have good feelings about Case Western Reserve, in general. It's where I figured out what I wanted to do with my life. And it's where I figured out my sexual orientation."

Shan Mohammed (MED '97)

Though Shan Mohammed was never out to his whole class as a medical student at Case, "There were clearly signs of support," recalls the clinical instructor in the School of Medicine. One such sign was the presence of a group sanctioned by the School of Medicine called Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered People in Medicine, which is a chapter of a national group sponsored by the American Medical Student Association. While Dr. Mohammed never joined the group, he found it comforting to know it existed, he says, noting that he chose instead to create his own network of support, which included a group of GLBT physicians in the region called the Northeast Ohio Physicians for Human Rights, who invited students to participate in their meetings and served as mentors.

A situation during his first year also had a strong impact on him. A student a year ahead of him was making a transition from being a woman to a man. The student sent a letter to fellow students explaining his transition process, so everyone would know what was going on, says Dr. Mohammed. "I think that student made a big impact on many students. That took a great deal of courage, I thought."

Another indication of the school's sensitivity to GLBT issues was a program, affectionately known as Gay Day, sponsored by the medical school. In the half-day program, students talk in small groups with gay and lesbian physicians, learning not only about the physicians' experiences as GLBT doctors but about the importance of being sensitive and alert to patients' concerns and sexual histories.

Though Dr. Mohammed remembers it being difficult hearing derogatory comments made about GLBT patients on the hospital wards, he considers his experience, overall, a positive one.

These days, Dr. Mohammed helps ease the way for medical school students who are GLBT. "Some of them aren't out and are suffering," he says, "which can be hard to see." On the other hand, he meets with a number of students "who are out and doing a lot better than I was doing when I was their age," he notes. "So I see hope and change and progress."

Brian Thornton (CWR '97; GRS '99, civil engineering)

During his years as an undergraduate student at Case, Brian Thornton recalls being disturbed one day when he came across chalkings for a Gay Lesbian Bisexual Alliance event that had been defaced, making him even less likely to come out of the closet.

The pink triangles announcing the event had been slashed with black painted lines. And Mr. Thornton recalls that several weeks passed before the defaced messages were removed, noting that the incident made a powerful impression on him.

For the first two years of his college career, Mr. Thornton never dated, concentrating instead on his studies as an engineering major. In his third year, however, he had a relationship with another male student. "We were totally in the closet about it," he says. "We couldn't tell anybody about it."

It wasn't until the summer between undergraduate and graduate school that he came out to his friends and attended his first gay-pride parade. Though he "embraced the whole gay scene," he couldn't bring himself to come out in the Department of Civil Engineering, he says, because he was well liked and worried about how he'd be perceived if people knew about his sexual orientation. So he chose to keep that part of his life secret. That's no longer the case today, as Mr. Thornton works as a community health advocate for the Lesbian/Gay Community Service Center of Greater Cleveland.

Valerie Molyneaux (CWR '99)

When Valerie Molyneaux attended Case in the mid- to late-'90s, she remembers being the "big lesbian on campus," she says, laughing, "I was one of the only lesbians here, it seemed." In her classes, and in the residence halls, where she eventually served as a resident director (when she was pursuing her master's degree at Kent State University), she often brought up GLBT-related issues. And because she was also involved in a feminist organization on campus ("and everybody assumes that feminists are lesbians"), and she and her partner held hands and embraced in public, she says, "People figured out I was a lesbian." Her partner, then and now, is Courtney Bryant (CWR '01), whom she met when both were students at Case.

With the exception of receiving some harassing phone calls, related to her sexual orientation, she doesn't remember experiencing any repercussions. The fact that she was comfortable with her identity and "didn't present an aura of being afraid," she believes, made a difference.

Though Ms. Molyneaux was involved with what was then the Gay Lesbian Bisexual Alliance (now called Spectrum), which was supported by the Undergraduate Student Government, she didn't find the university administration to be especially supportive of GLBT people. For several years, there were anti-gay chalkings in response to GLBA-sponsored events; and, she says, "basically the administration didn't take a stand on it. And because of that, there was the sense that gay students were tolerated but not supported."

Still, Ms. Molyneaux, who now serves as an area director at Emory University, finds hope in the fact that the university agreed to extend benefits to domestic partners of Case employees.

The University supports GLBT people in the campus community through a variety of policies, groups, services, and programs. Listed below is a rundown of some of those signposts of support:

Policies

- In 1989, the University added sexual orientation to its anti-discrimination policy;

- In January 2000, CWRU began offering benefits to domestic partners of University employees.

GLBT Groups*

- Spectrum: a social and activist group for GLBT undergraduate students and straight allies. Holds weekly meetings, and plans social and activist events, including the Lavender Ball, National Coming Out Day, and the Day of Silence;

- Queer Society – A newly formed social group for GLBT people at CWRU;

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered People in Medicine: a political and social organization for students in the School of Medicine that aspires to conduct community service projects and advocate for GLBT health-policy issues;

- Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences Group for GLBT Students: a social and activist group for students in that school;

- FLAG Law (Friends, Lesbians, and Gays in Law): a social, political, and activist group for students in the School of Law that aspires to cosponsor GLBT-related lectures, conferences, and other events with student organizations on campus and in the community.

Services and Programs

- Office of University Counseling Services: offers individual counseling for GLBT students (and all students) designed to help them through the coming-out process, and also offers couples counseling (for homosexual and heterosexual couples). The office also provides staff support for events such as National Coming Out Day and sponsors an annual pizza party, welcoming graduate and professional students to the University. The event, held in August, allows students to meet faculty, staff, and students who are GLBT;

- Office of Multicultural Affairs: houses CWRU’s Spectrum group and offers members of Spectrum the chance to interact with other students from under-represented and under-served groups on campus;

- Office of Housing and Residence Life: sponsors programs in the residence halls that incorporate GLBT issues and provides staff support for GLBT-related events. Also provides an intensive training program for resident assistants and resident directors that focuses on diversity and incorporates GLBT issues;

- Gay Day: a half-day-long program in the School of Medicine in which GLBT physicians talk to medical students about the importance of being sensitive to the needs and issues of people who are GLBT and the value of taking sexual histories so patients can be best treated.

Events

- Sex, Drugs and Rock and Roll Conference: a University-sponsored event that seeks to promote responsibility in relationships, prevention of substance abuse, and the discussion of popular music and culture in relation to the lives of college students. Some discussions include GLBT-related topics;

- Freshmen Orientation: This introduction to life at CWRU covers a variety of topics such as campus safety, student life, and diversity, which touches on GLBT issues. For the past three years, a reception for GLBT students and their families has been held during orientation. It is sponsored by University Counseling Services, PFLAG-Cleveland, and Spectrum.

* In the past, there have been other University-funded groups on campus, including one for graduate students. In the past couple of years, however, students in this school have not requested funding.

The information below, gleaned from resources described on college and university websites, offers an abbreviated listing of the programs, groups, and activities that some of CWRU's peer institutions provide for GLBT people on their campuses. No attempt was made to determine to what degree these services are used or how active the groups are. All of the colleges and universities listed in this section make available some form of benefits for domestic partners of employees. Some also extend benefits to the domestic partners of students.

Dartmouth College

- Coordinator of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Advocacy and Programming in the Office of Student Life: This staff member provides advising to individual students and the Dartmouth Rainbow Alliance, organizes gay-related educational and social events, provides training and workshops, and represents the needs and concerns of GLBT students to the college administration;

- Dartmouth Rainbow Alliance: a student organization for people who are GLBTQ (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning);

- Queer Peers: a listing of students, faculty, staff, and administrators who are willing to be resources and supportive of GLBT members of the Dartmouth community;

- Gay Straight Alliance;

- Coalition for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Concerns: the organization for faculty, staff, and administration;

- Green Lambda: An GLBT group for graduate and professional students;

- DGALA: Dartmouth's Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Alumni Association.

Duke University

- Center for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Life: Staffed by full-time faculty and staff, it offers advocacy, support, education, and space to the GLBT and straight-allied community;

- In and Out and In Between: a group for people across the spectrum;

- SpeakOut: panel discussions in which GLBT people and heterosexual allies share their stories and respond to audience questions;

- Queer Grads: a group for graduate and professional students;

- Out Law: a student group in the School of Law;

- Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Alliance in the School of Business;

- Triangle Queer Buddhists: a group for GLBT people interested in learning about Buddhism.

Emory University

- Office of Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender Life: staffed by full-time professionals and by students who work part time. Offers programs and services designed to "improve the campus climate and create an open and welcoming environment for LGBT students and employees";

- President's Commission on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Concerns: an advisory board to the president that meets once a month to consider university-wide policies and procedures that will improve the overall campus atmosphere for LGBT faculty, staff, and students;

- Safe Space Program: Participants in the program attend a short orientation session conducted by members of the Office of Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender Life Speakers Bureau, then receive a logo to display that shows they support the right of LGBT people to study and work in a safe and welcome atmosphere;

- Emory Pride: open to all students, staff, faculty and their allies;

- Emory Gay and Lesbian Advocates: a group for GLBT law students.

Johns Hopkins University

- Gertrude Stein Society: an organization for LGBT members of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, including the Schools of Nursing, Public Health, and Medicine;

- Diverse Sexuality and Gender Alliance: a political, social, and support organization committed to promoting visibility, equality, and a sense of community for transgender, bisexual, lesbian, gay, and straight allies.

New York University

- Office of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Student Services: The office is intended to create campus environments that are inclusive and supportive of student diversity in terms of sexual orientation and gender identification. Offers weekly discussion groups for students. Features a lending library and publishes a newsletter for the campus community. Also features a Safe Zone project, which identifies a network of students, faculty, and staff who provide support and information to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students;

- Bisexual Gay and Lesbian Law Students Association: a group with a political, social, and educational mission;

- Queer Union: NYU's social, support, and political organization for undergraduate and graduate GLBT students;

- Keshet: a GLBT group for Jewish students;

- Fluidity: a group for people who are bisexual and transgender;

- CampGrrl: a social group for lesbian, bisexual, and transgender women;

- Queers and Allies: a group for allies interested in supporting their LGBT peers;

- T-Party: a group for transgender students and their allies.

Northwestern University

- Bisexual, Gay and Lesbian Alliance: a social and support group primarily for undergraduate students;

- OUTLaw: a group for Northwestern law students;

- Gay and Lesbian Management Association: provides professional and social support for gay and lesbian students;

- GLUU: primarily a social group for graduate students, faculty, staff, and alumni who identify as GLBT;

- GLBT and Greek: a support group for sorority women who identify as lesbian or bisexual or are questioning their orientation. Sponsored by the Women's Center;

- Safe Space Program: a network of people who provide support, information, and a safe place for GLBT people within the campus community.

The University of Chicago

- Pritzker School of Medicine's Chapter of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual People in Medicine;

- The Pritzker Medical School has a Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Medical Student liaison who answers questions and places students in contact with other students at the university;

- Queers and Associates: a university-wide GLBT organization open to graduate and professional students and undergraduates;

- Lesbian and Gay Faculty and Staff Organization;

- Outlaw: an organization that provides a supportive atmosphere for gay and lesbian law students;

- Gays and Lesbians in Business: provides a social and educational network for GLBT members of the Graduate School of Business.

The University of Rochester

- Gay Pride Network: provides a supportive environment and social activities for students and other constituencies on campus;

- Safe Zone project: provides support and information to GLBT students.

Vanderbilt University

- Vanderbilt University Office for GLBT Life: coordinates GLBT activities and offers support to students;

- VGPLBG (Vanderbilt Graduate and Professional Lesbian/Bisexual/Gay Student Association): an organization for gay, straight, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender graduate and professional students, graduates, faculty, and staff of the Vanderbilt community;

- Office of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Concerns in the Divinity School: addresses the issues of homophobia and heterosexism in religious life, society, and the academy;

- Gay and Lesbian Law Students Association;

- Vanderbilt Lambda Association: an organization for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and straight students.

Washington University in St. Louis

- Spectrum Alliance: a social and political group targeting the GLBTQ (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning) population as well as straight allies;

- Safe Zone.

I applaud the magazine for publishing the article on the realities of being gay at CWRU. However, there was a point with which I must take issue. Glenn Nicholls was quoted as saying that hate speech or graffiti with anti-gay content requires a balancing act, as the University is obligated to protect free speech. I have to ask: If someone used a more familiar epithet concerning a person of African-American heritage, or of the Jewish faith, would the response be as tentative? I am saddened that the University apparently believes that some hate speech is less harmful than others. We need to educate the young people of our country that intolerance against anyone who is different from ourselves is not acceptable under any circumstances. Universities and colleges have a moral responsibility to treat anti-gay bias as aggressively as any other bias.

John Bradley (GRS '88, theater), New York City

I agree that we would like to see CWRU, as well as universities across the country, become more tolerant of LGBT issues (and other issues). However, I do not agree that we can tolerate "hate" messages on campus as a means of allowing for "free speech." Although free speech is a well-known American right, should we have a lax response to hate crimes or hate messages sprawled across campus? My opinion: absolutely not.

Feel free to have a different opinion than mine, and express it in a non-hateful manner. I will listen. Don't ask me to look the other way when someone behaves badly, all in the name of freedom. My definition of freedom does not exclude the concept of respect. And I certainly cannot advocate that our campus adopt such a definition.

A strong message ought to be sent. Our vice-president for student affairs is not sending that message. He is promoting the hostility he insists does not exist. Hate is not freedom.

Mary Beth Lipka, Staff member, CWRU

"When a short-haired woman was walking across campus, a male student hurled these words at her across an open green: 'You're a f***ing dyke!'" As a homosexual, I feel obliged to ask: What would the reaction have been, and what disciplinary action taken, had the word been "nigger" or "kike"? From their omission in the listing of this assault, I am left to conclude there were neither from other students, faculty, etc., who witnessed this example of homophobia.

How is it the University still tolerates this kind of behavior? One of my most pleasant memories of WRU's graduate school was a relationship I had there. Was it because I lived with the more mature, or more diverse, population in the Graduate House that I was spared such abuse? This is not childishness; it is pure, unadulterated hatred. It has no place anywhere, but most particularly not in a university of CWRU's caliber.

Possibly more alarming is the story of the law student who chose the law school because there were "fewer queers and fags than at other schools." A law student. One can only hope he flunked out and is not going to be able to practice law against us. What kind of representation could we expect at his hands?

CWRU has the obligation to protect all of its students and to ensure that all have equal opportunity. It should set the standard, leading by example. Punishing such behavior as the woman was a victim of, and showing that homosexual faculty and staff are treated equally are two obvious ways to do so. I was active in the New York Alumni Association for many years, trying to encourage prospective students to attend CWRU. I can only hope they weren't exposed to such intolerable behavior.

John H. Turner (GRS '64, theater), Indianapolis

Glenn Nicholls, vice-president for student affairs, responds: I applaud CWRU Magazine for publishing "Beyond the Silence," as well as the letters in this section. Both serve to reinforce the importance of this issue and the value of open dialogue on our campus. The three letters above identify numerous points with which I agree completely, including fostering understanding and tolerance, the responsibility to ensure all of our students are valued and treated equitably, and that responses to anti-gay bias should be just as firm as responses to any other harmful bias.

I regret that my choice of words at the end of the article gave the impression to some readers that this is not the case. Hate crimes and hateful behavior should be and are responded to as what they are, unacceptable on this campus. It is also true that our campus is committed to the free and open exchange of opinions and ideas. In those exchanges, it is inevitable, and at times invaluable, that there will be disagreements and even conflict. Ideas that some cherish will be unimportant to others, and some strongly held opinions will even be offensive to others. When speech is restricted, the result is usually negative. For example, one prominent campus adopted a speech code and found the vast majority of complaints were filed against the very group the code was designed to protect. The balance to be struck is to address hateful behavior while protecting free speech, even speech that we disagree with.

What a wonderful piece, "Beyond the Silence." I must say that I am happy to see some progress has been made on this issue since I was at CWRU. I am happy to hear that the University is attempting to do something. But mostly, I wanted to acknowledge you for taking the time to publish this.

Richard Wortman (LAW '87), Los Angeles

The good news of the new leadership at CWRU, which the summer edition of CWRU Magazine brought to us, was, in my opinion, more than offset by the article "Beyond the Silence." As this article states, it is about "what the University is doing to make the campus a more accepting place" for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender students, faculty, and staff.

Since the magazine is a publication of the University, I assume the article expresses the position of the University and the new leader—President Hundert. If the article was to welcome these students and to say that every effort was being made to turn them away from antisocial and anti-Christian behavior, I would be writing to applaud the University's efforts.

However, the article indicates that efforts are and will be made to welcome, recognize, and make them comfortable.

In light of this, please remove my name from the alumni contributors and do not in the future call me.

James S. Price (ADL '46), Advance, North Carolina

After I finished reading my copy of the spring 2002 CWRU Magazine back in May, I was excited to find that the next issue would have a story on the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered community at CWRU. I anxiously awaited the next issue and was not disappointed. As a past president (1993 to 1995) of the Gay Lesbian Bisexual Alliance (now Spectrum) at CWRU, I can't tell you how much a story could mean to so very many people--students, faculty, staff, and alumni alike. It has been my impression that, while the administration of CWRU has always been tolerant and protective of the GLBT students, staff, and faculty, the issues surrounding the GLBT community's needs for equality also so often get pushed under the rug.

While I was a student, I tried hard to make the GLBA a recognized and respected group on campus, among both students and the administration. We worked to establish a presence, so that people in the CWRU community who were just coming to grips with their own sexuality, as it may differ from others, would have somewhere to turn, so that they would know there was a safe and accepting place for them. I believe we made a good start, and it is my impression that the current leaders of the Spectrum group have done very well indeed. We worked often with the Dean of Student Affairs and President Agnar Pytte and found willing ears; although, as far as policy goes, nothing ever seemed to truly get accomplished. In particular, we worked to bring domestic partnership benefits to the faculty, staff, and students of the University. I graduated without seeing that come to fruition, but was gratified to see in the article that, two years ago, the University began to offer such benefits. It is my hope that they will soon equal the benefits of the spouses of heterosexual students, faculty, and staff of CWRU.

If CWRU wants to be on the leading edge of higher education, it must recognize that tomorrow's students and faculty will require of it leading-edge thinking. I'd like to encourage and challenge the CWRU administration to take those steps in attempts to bring equality to all its faculty, staff, and students; to make bold statements that will allow gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered people to feel that CWRU is a safe place for them; and, in doing so, to challenge CWRU's peer universities to do the same.

Christopher J. Hinkle (CWR '96)

"Beyond the Silence" touched me deeply. I graduated in 1975 as an undergraduate at CWRU. I began to come out to myself in my senior year (and at the same time was "pinned" to a woman). That the University acknowledges, let alone discusses, that there are GLBT students is a huge step forward.

Back in the day, we were actively working to stop the Vietnam War, we embraced environmental causes, we stood against racism—in short, we were good Midwestern liberals. However, when it came to being out, to embracing gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and questioning causes, the University was not so progressive. The '70s may have been all about bringing in everyone under the big tent, but the tent did not seem to have a rainbow section. I was not out at CWRU. My friends, some of whom, like me, realized their gayness later in life, were not out. There were brave brothers and sisters who were out in the '70s, and I, like most "straight" students, steered way clear of them and their cause.

How sad and ironic that the period in life in which the most phenomenal growth in my spirit and my world occurred, also was a period when I felt utterly alone in, and frightened of, my sexuality.

Even though I live with a partner of twenty years, even though I am out on the job, out in a supportive church, out to my family, out to my other GLBTQ brothers and sisters, I look back on my University days as a great lost opportunity. The truth lies somewhere between history, geography, and personal dynamics, and the truth is that what might have been a time of real coming to terms with me was more a time of total escape from who I was. I still suffer the negative effects of living large and in the closet—transparent as it might have been—while at CWRU.

Your article and website touched a raw nerve. For that I am eternally grateful.

David J. Habert (WRC '75), San Francisco

I enjoyed reading "Beyond the Silence." I think this is an important place for the University Health Service to play a role as well. A number of years back, when I was asked to see a transgender student for a complication of her gender reassignment surgery, I found that I needed to learn much more about this area--and so I did. I embarked on what turned out to be a fascinating learning experience for me. Then, I felt obligated to go further and put this to use, by giving a talk titled "The Primary Care of the Transgender Student" at the Annual Meeting of the American College Health Association. I still think that sensitivity to trans issues is not as far reaching as for other GLB issues.

Eleanor Davidson, Director, CWRU's University Health Service