CLEVELAND NICKNAMES AND SLOGANS reveal a cultural history of boosterism and varying local and national perceptions of Cleveland that was driven by economic, political, and social landscapes. The original names for Cleveland stemmed from Native American identifiers for natural landmarks and the history of Connecticut’s connection to the Northeast Ohio area. Cleveland’s first nicknames - FOREST CITY, Sixth City, and Fifth City - were early testaments to Cleveland’s forest environment in the mid-1800s and the population growth as the result of industrialization in the early 20th century. After WORLD WAR II, marketing Cleveland became relevant to continue to build the region economically; however, the mass movement to the SUBURBS in the 1950s and 1960s led to economic decline in the city of Cleveland, and thus, challenging the marketing campaigns. From the 1950s through the 1970s, Cleveland boosterism tried to put a rosy tint on a declining city, and was often in discord with the perceptions of those living in the city, especially the growing population of AFRICAN AMERICANS. The 1969 CUYAHOGA RIVER FIRE led to further image decline and manifested in the form of Cleveland jokes and negative nicknames. These nicknames, slogans, and jokes were further substantiated by the continued economic decline and accompanying political issues throughout the 1970s into the 1980s. The tactics for official slogans shifted in the 1980s to focus on Cleveland’s unique aspects, such as its history of ROCK ‘N’ ROLL and pride in its lakefront. A cultural revolution came about the 1990s and 2000s when the local populace began to generate and popularize nicknames, many of which came from the intersection of the black community and the hip-hop and rap scene. The more current marketing campaigns of the 2000s through 2022 have avoided the overt boosterism of the past and instead have attempted to align with popular culture as well as promoting the city’s changing ECONOMY and its environmental improvements. The LeBron James slogan “In Northeast Ohio, nothing is given. Everything is earned” and the nickname “Believeland” played a role in boosting pride in the city during and following the CLEVELAND CAVALIERS victory in the 2016 National Basketball Association (NBA) Finals after many decades of disappointments in sports. The following periodization of Cleveland’s nicknames and slogans provides an abridged history of the city’s character development.

Early Names

The first names to describe the area of the Cleveland and Northeast Ohio region were its greatest natural landmarks - Lake Erie and the CUYAHOGA RIVER. Both names are of Native American origin. Cuyahoga was supposedly derived from the Mohawk word for “crooked” and the Seneca word for “place of the jaw bone” - both referring to the sharp twists of the river. The name “Erie” came from the ERIE INDIANS who once populated the easternmost part of Lake Erie in modern Pennsylvania and New York. Erie was supposedly derived from a French understanding of the Huron-Native name for the Erie people that means “it is long-tailed,” which referred to the Erie people’s association with wild-cats. Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River are closely intertwined with the area’s history and identity both before and after European intervention.

The first European-given names for the region were New Connecticut and the Connecticut WESTERN RESERVE, or Western Reserve for short. Connecticut’s 1662 royal charter granted the land to the west of the colony “from sea-to-sea." Connecticut surrendered its western lands to the newly established United States government, as did other states. All the land states relinquished to the west became the Northwest Territory under the Ordinance of 1787, which was made up of modern-day Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and northeastern Minnesota. However, Connecticut retained the Northeast Ohio area, known as the Western Reserve, as compensation for the land the state relinquished or which had been infringed upon by other states such as Pennsylvania. The state of Connecticut then sold the 3 million acres of the Western Reserve to the CONNECTICUT LAND CO. on 2 September 1795 for $1.2 million. The “Western Reserve” name continues to appear in 2022 in some of the oldest institutions in the Cleveland area including the WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY and CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY.

MOSES CLEAVELAND, stakeholder in the CONNECTICUT LAND CO., led the first surveying party to the WESTERN RESERVE in the spring of 1796. The Cleaveland family name was said to have originated from Yorkshire, England with Saxon origins to a large landed estate that contained cracks in the landscape described as “cleves” or “clefts.” During the 1796 expedition, Cleaveland chose the current site of the city, as what might be considered the “capital” of the Connecticut Western Reserve, based on the potential economic advantages of being on the mouth of the CUYAHOGA RIVER. According to Harlan Hatcher’s The Western Reserve: The Story of New Connecticut in Ohio, Cleaveland planned on naming the settlement “Cuyahoga” because of the significance of the river to the new settlement; however, Cleaveland’s surveying party convinced him to name the settlement “Cleaveland” after himself. The “Cuyahoga” name was then later used in the establishment of Cuyahoga County in 1810 of which Cleveland was a part. In October 1796, Moses Cleaveland’s party headed back to Connecticut and Cleaveland never returned to the city that bears his name.

Cleaveland, named after the surveyor, eventually became Cleveland, minus the “a,” in a prolonged and unclear transitional period. Both spellings appear in the first maps of the area. The modern spelling of Cleveland, minus the first “a,” was made official on 23 December 1814 when the Ohio Legislature passed the official document to incorporate Cleveland as a village. However, “Cleveland” and “Cleaveland” were both used in the settlement until around the 1830s when two of Cleveland’s newspapers, the CLEVELAND ADVERTISER followed by the CLEVELAND HERALD AND GAZETTE, dropped the “a” from their masthead. The most popular story of why the “a” was dropped from The Herald was because of lack of space in the newspaper heading. Cleveland: The Making of a City by William Ganson Rose asserts, “Records of Cleveland Township show the “a” in general use until about this time [1830s].”

First Nicknames

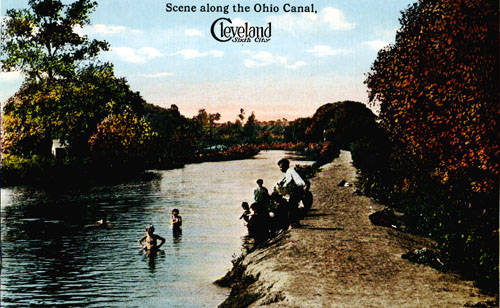

FOREST CITY was likely Cleveland’s first nickname and was coined in the 1850s. “Forest City” refers to a tree planting program initiated by Cleveland Mayor WILLIAM CASE in the 1850s, which came about from his interest in horticulture. Case was most often given credit for the nickname; however, TIMOTHY SMEAD, an early Cleveland printer, also claimed to be the source of the nickname. After 1850, numerous organizations and businesses took up the nickname and it is still used in 2022.

At the turn of the 20th century the city gained nicknames based on its substantial growth - “Sixth City” and “Fifth City.” Both nicknames stemmed from Cleveland’s pride in the early 20th century for being one of the largest city populations in the United States according to census reports. Cleveland boasted one of the top-ten slots for largest city population in the United States Census between 1890 and 1970. In the 1910 census, Cleveland rose to become the sixth most populated city in the United States by overtaking Baltimore. A PLAIN DEALER article from September 1910 described the celebration at the Chamber of Commerce (see GREATER CLEVELAND GROWTH ASSN.) upon receiving the news with the hopes of one “million in 1920,” which would have been monumental with Cleveland’s 1910 census reporting a population of 560,663. Another Plain Dealer article from July 1911 wrote, “The Chamber of Commerce of Cleveland asks the business men of the city to use the phrase, ‘Cleveland, Sixth City,’ in their correspondence and on all their commercial printed forms.” Throughout the next decade, “Sixth City” was proudly used in postcards, advertisements, and articles. There were frequent speculations about the city’s rise to the fifth slot in the 1920 census. It did, indeed, achieve the rank of “Fifth City” in the 1920 census behind New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Detroit. As “Sixth City” took off in terms of use in 1910, “Fifth City” was also regularly used as a point of pride throughout the 1920s. In the 1930 census, Los Angeles took over the fifth slot and Cleveland once again became the “Sixth City,” which was maintained in the 1940s census. After 1950, Cleveland’s population ranking steadily dropped and its rank no longer spurred any nicknames.

Marketing Cleveland, Part 1, 1940s-1970s

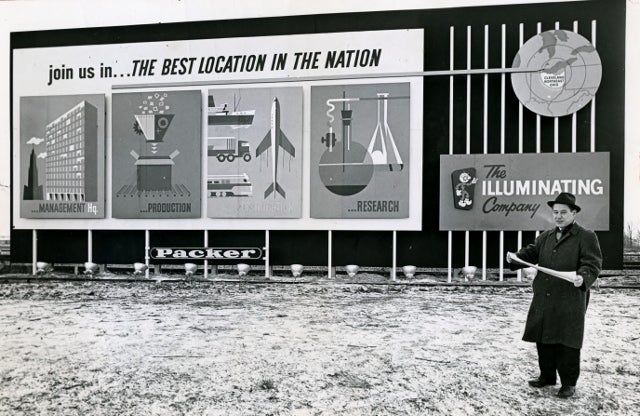

In 1944, the CLEVELAND ELECTRIC ILLUMINATING CO. (CEI) launched a marketing campaign to claim Cleveland as “The Best Location in the Nation” in order to take advantage of the post-war boom and expand business in Northeast Ohio. CEI during this period was the leader in the Northeast Ohio ELECTRIC INDUSTRY with a 1,800 square-mile service area, but was also a “producer of machine tools, electrical goods, metal products, and paints and varnish,” according to Carol Poh Miller and Robert A. Wheeler’s Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796-1996. Their strategy with this campaign was to create and expand their customer-base to capitalize on their multiple product lines. The campaign’s boosterism led to broader support from other local organizations including the Chamber of Commerce (see GREATER CLEVELAND GROWTH ASSN.) and newspapers.

CEI’s “The Best Location in the Nation” campaign was promoted in multiple channels including commercials, billboards, and media articles that emphasized Cleveland’s geographic and resource advantages. The campaign noted that within a 500 miles radius from Cleveland producers and industries could find a market comprising economic centers containing half of the people living in the United States and Canada. That area also included vast deposits of natural resources that were easily transportable by water, highway, railway, and air. These advantages combined with a large, regional skilled workforce made a compelling argument for the nickname CEI had created.

According to Mark Souther’s Believing in Cleveland: Managing Decline in the Best Location in the Nation, CEI’s campaign and community-growth strategy encompassed not just Cleveland, but the Northeast Ohio region. Thus, CEI and other major utility and TRANSPORTATION companies encouraged industries to spread into the Cleveland SUBURBS with the goal of expanding the entire region economically. This strategy came with the assumption that Cleveland would naturally remain as the center for INDUSTRY. Throughout the 1950s, many businesses located within the boundaries of the city moved to the suburbs or out of state for economic reasons and to better support larger, more modern and efficient facilities. Cleveland’s industrial infrastructure was becoming increasingly out-dated and it became financially beneficial to build new plants. At the same time, the white workforce living in the city was moving to the suburbs because of increasing family size, the availability of better housing and amenities, the increasing ease of commutes due to highway systems and wider-use of cars, and racial bias. The growing AFRICAN AMERICAN population in the city resulted in a "white flight," which was impelled in large part by the REAL ESTATE industry utilizing "block busting" strategies based on a fear of decreasing values of homes within newly integrated areas. Because of the rapid movement to the suburbs, Cleveland was left in a state of economic decline. The declining results of the campaign in the early 1960s caused CEI to drop the “Best Location in the Nation” campaign.

The Greater Cleveland Growth Board (GCGB) (see GREATER CLEVELAND GROWTH ASSN.) took CEI’s place as regional promoter and continued the “Best Location in the Nation” campaign. The GCGB was created in the early 1960s to control the image of the city’s decline, promote the Greater Cleveland area to new business, and attempt to retain businesses other cities were actively recruiting. The GCGB ran multiple marketing campaigns including “The Greater Cleveland Growthland” slogan and continued to leverage the slogan and messaging of the “The Best Location in the Nation” campaign. It emphasized Cleveland’s future in space technologies with Cleveland’s research universities and the NASA JOHN H. GLENN RESEARCH CENTER AT LEWIS FIELD. With “Best Location in the Nation” becoming increasingly difficult to substantiate to business owners, the GREATER CLEVELAND GROWTH ASSOCIATION, which merged with the GCGB, retired the old campaign in the early 1970s in favor of a fresh concept.

The GREATER CLEVELAND GROWTH ASSOCIATION (GCGA) launched the “Best Things in Life are Here” campaign in 1974 to target the corporate elite by emphasizing Cleveland’s business advantages and the recreational and cultural amenities such as the CLEVELAND METROPARKS and the CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, according to Mark Souther’s Believing in Cleveland: Managing Decline in the Best Location in the Nation. Cleveland was the third-place ranking city in the United States for company headquarters and the space-age technology industry was supposedly developing. The campaign included promotional merchandise, ads in national media, and a brochure titled 15 Minutes outlining reasons why Greater Cleveland was a good place to live. However, the campaign had to tackle Cleveland’s declining reputation as economic, environmental, and social problems were gaining national attention through the advent of Cleveland jokes. While the campaign recognized the economic situation was much different from the “Best Location in the Nation” campaign, some of the elements were repackaged. Therefore, the “Best Things in Life are Here” campaign inherited the criticisms of the previous campaign such as ignoring the most pressing issues of the region and the focus on a narrow band of elite outsiders. Locals did not embrace the slogan and even openly criticized the campaign.

Cleveland’s Image Decline, 1960s-1970s

Cleveland’s economic woes, environmental problems, political turmoil, and systemic race issues in the 1960s and 1970s led to a steep decline in Cleveland’s local and national image to create a new nickname - “Mistake on the Lake.” The economic decline and racial tensions of the 1960s ended with the infamous 1969 CUYAHOGA RIVER FIRE that brought negative national attention that further resulted in what might be termed an inferiority complex among Clevelanders throughout the 1970s. Exacerbated by jokes, and other events such as Cleveland’s municipal DEFAULT in the late 1970s and the 1978 RECALL ELECTION of Mayor Dennis Kucinich (see MAYORAL ADMINISTRATION OF DENNIS J. KUCINICH), combined to create a persistent atmosphere of what might be called civic despair.

The phrase “The Mistake on the Lake,” sometimes referred to as “The Mistake by the Lake,” emerged in the early 1960s as a reaction to the bolsterism of the “Best Location in the Nation” campaign that focused exclusively on the good in Cleveland to attract new business and tourists, but ultimately ignored the wide-spread issues of the Cleveland populace. The growing population of AFRICAN AMERICANS living in Cleveland were experiencing economically-debilitating racial discrimination. In the 1950s, when the “Best Location in the Nation” slogan was the strongest, the African American population experienced REAL ESTATE housing issues on a systematic scale. As the African American population grew in East-side neighborhoods such as CENTRAL, HOUGH, and GLENVILLE, housing opportunities were declining due to “discriminatory bank and real estate practices,” according to Mark Souther’s Believing in Cleveland: Managing Decline in the Best Location in the Nation. As a result, neighborhoods became overcrowded as landlords subdivided houses and charged a premium. All the while, Cleveland schools remained de facto segregated. One CLEVELAND CALL & POST article from December 1953 said, “If Cleveland wants this title [Best Location in the Nation], deservedly, let these officials move boldly in the face of race hatred and bigotry, and build housing on every vacant foot necessary to house Cleveland properly.” The “Mistake on the Lake” nickname first appeared in print in a May 1964 Cleveland Call & Post letter to the editor written by a Glenville woman on a series of events involving the integration of a Cleveland mostly-white school. She said, “Instead of living in the ‘Best Location in the Nation,’ I now reside in ‘The Mistake on the Lake.’” The two nicknames regularly appeared in contrast to one another throughout the 1960s, mostly referring to deteriorating RACE RELATIONS. In July 1964 the nickname’s first mention in Cleveland Call & Post, Clarence Holmes, the president of the Cleveland chapter of the the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP), was quoted in the PLAIN DEALER for similarly contrasting the slogans “The Best Location in the Nation” and “Mistake on the Lake.”

A brief glimpse of hope was found in the Cleveland mayoral campaign and subsequent administration of CARL B. STOKES, the first African American mayor of a major American city. The Stokes campaign contained a number of slogans, all promoting pride in Cleveland including “I Believe in Cleveland” and “Let’s Do Cleveland Proud.” The “Believe in Cleveland” slogan appeared in full-page newspaper ads with a letter from the Stokes campaign with hopeful messaging. Members of the Metropolitan Civic Club supported the Stokes’ election campaign with “Let’s Do Cleveland Proud” campaign signs while giving away campaign brochures, buttons, and posters at CLEVELAND MUNICIPAL STADIUM. The messaging resonated with the Cleveland community, particularly the AFRICAN AMERICAN community. When Stokes won his campaign, The CLEVELAND CALL & POST celebrated the victory in November 1967, noting a group of women prayed together, exclaiming, “Thank God, for peace and unity in Cleveland!” During his MAYORAL ADMINISTRATION, Stokes instituted the “CLEVELAND: NOW!” Plan that raised money for civic improvements that included urban renewal projects around housing and other visible changes to the city such as installing new street lighting. However, the comeback under Stokes was hindered by continued economic decline and racial unrest, particularly during the GLENVILLE SHOOTOUT.

The CUYAHOGA RIVER FIRE of June 1969 became an infamous milestone for environmentalism in Cleveland, but also evolved the meaning of “Mistake on the Lake” and ignited a long-stream of Cleveland jokes that would affect the city for years to come. The 1969 river fire did not immediately attract local attention because it lasted 20 minutes and caused less damage than previous fires due to deindustrialization and interventions to improve the river quality. About a month later, Time magazine published an article about the fire with a picture from the more severe November 1952 fire on Cuyahoga River, taken about 17 years earlier, since there were no pictures taken of the 1969 fire. The article and subsequent media attention sparked concern about ENVIRONMENTALISM, not just in Cleveland, but in the nation. As a result of the fire, the Clean Water Act of 1972 was passed by the United State Congress and Earth Day was held in April 1970 with Cleveland having some of the highest participation in the nation. All the while, the fire inspired a long list of Cleveland jokes, many of which poked fun at the city where the river catches on fire. Nicknames and slogans like “Pollution City,” “Welcome to Blight City,” “Greetings from Flammable Cleveland!,” and “The only city in the world with a river that caught fire” emerged. Even Randy Newman released the song “Burn On” in 1972 about the fire, “Cleveland, city of light, city of magic… Cause the Cuyahoga River goes smoking through my dreams.”

The fire sparked Cleveland’s national reputation for being a joke punchline. Most of the jokes stemmed from local Cleveland comics who worked for TV networks in Los Angeles. One of these Cleveland comics was Jack Hanrahan, who was the script supervisor for the NBC show Laugh In. The show received complaints about ethnic jokes, so Hanrahan and his writing team switched them out for Cleveland jokes. Jack Riley, another comedy writer, recounted that the 1969 CUYAHOGA RIVER FIRE was “a natural for laughs,” but there was not any “malice” intended. Other jokes were made about the city when Cleveland Mayor RALPH PERK’s hair accidentally caught on fire while he was using an acetylene torch to cut a ribbon for the opening of a metals show. Hanrahan received an Emmy Award in 1970 for his work on Laugh In. Hanrahan was quoted in a February 1979 PLAIN DEALER article saying, “So, I sat down at the typewriter and pounded out a few jokes about a city I dearly love and then things began to snowball. Soon every comic around was doing Cleveland jokes. That part I regret.” Cleveland jokes continued to appear in the media regularly, including the Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, throughout late-night stand-up routines and other media. The jokes started to ease sometime in the 1980s, but the effects of the jokes in the national psyche have lingered.

The “Mistake on the Lake” nickname gained wider use after the 1969 CUYAHOGA RIVER FIRE and became a regular nickname for Cleveland throughout the 1970s and 1980s. One letter to the editor in the PLAIN DEALER from December 1970 wrote, “National Geographic magazine came to the ‘Best Location in the the Nation’ to find the perfect example of foul water, in the form of a three page panorama of the inflammable Cuyahoga River… we should change our motto to ‘The Mistake on the Lake.’” The lakefront CLEVELAND MUNICIPAL STADIUM was also dubbed the “Mistake by the Lake” in the 1980s due to its old-fashioned design and the declining state of the historic structure. Sometime in the late 1980s and 1990s, Plain Dealer articles began to talk about Cleveland previously being the “Mistake on the Lake,” but no longer.

“The Mistake on the Lake” nickname, the 1969 CUYAHOGA RIVER FIRE, and the associated Cleveland jokes spurred a broad conversation about the city’s negative perception and whether or not it deserved it as well as the future of Cleveland. Each assessment ultimately depended on the topic and the writer. One PLAIN DEALER article from September 1975 interviewed industrial psychologist Dr. Erwin S. Weiss to assess Cleveland’s image issues. Weiss attributed Cleveland’s image issues to a lack of unified civic identity because of the rapid fragmentation between the SUBURBS and the city in the 1950s that has resulted in a sense of pent up frustration and hopelessness on all sides that Cleveland’s issues will improve. The article went on to explain how Cleveland residents stopped trusting in the GOVERNMENT and the ECONOMY to provide the necessary elements for prosperity. And those in the suburbs defended Cleveland by citing the “too few, and often irrelevant, civic features,” said Weiss, that do not “appeal to the masses.” Rather, “the masses” relate more to Cleveland sports for their sense of pride in the city. Weiss blamed the city officials for resolving problems with “superficial actions,” such as rosy-booster marketing, instead of taking concrete actions to unify Cleveland like making areas more accessible by public transit. Weiss’ assessment of Cleveland’s image was one professional’s opinion in a sea of civic opinions on Cleveland’s future. The discussion on Cleveland’s evolving, and what some might say as improved, image continues in the 2020s.

Ironically the result of the “Mistake on the Lake” mentality of the 1970s, resulted in Clevelander’s adoption of a new narrative focused on being tough and having thick skin. In the late 1970s and 1980s, Dan Gray, known as Daffy Dan, created a popular t-shirt printing business that brought about the slogan, “Cleveland: You’ve Got to Be Tough!” The slogan was printed on t-shirts and sold at the chain of Daffy Dan’s t-shirt stores around the Cleveland area. The t-shirt was reportedly worn around the city and the slogan appeared among the “5 Best T-Shirt Slogans of 1978” in the PLAIN DEALER.

Marketing Cleveland, Part 2, 1980s-1990s

Official Cleveland marketing campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s had to take a different approach due to the negative press and jokes from the previous decades. Two campaigns of the 1980s promoted the unique aspects of Cleveland - “America’s North Coast” and “The Rock’n’Roll Capital of the World.” The slogan “Cleveland is a Plum” took another approach - a highly creative slogan that captured the public’s interest. They created more approachable marketing campaigns that appealed to wider audiences than previous decades.

The nickname “Cleveland: America’s North Coast” was popularized in the early 1980s by a local ad agency owner and was eventually used as the official tourism slogan for Cleveland. Describing Cleveland as America’s “North Coast” first appeared in a 1963 Greater Cleveland Growth Board (see GREATER CLEVELAND GROWTH ASSN.) ad, “a new North Coast of America,” to promote Cleveland as a port city. In the late 1970s, James Semsak, a local ad agency owner, sought to create a slogan that Cleveland locals could embrace that was not directly aimed towards economic development as were previous campaigns. Semsak’s firm developed a simple, but impactful t-shirt design of a lighthouse and seagulls that was quickly embraced by locals. This captured the attention of the GCGA and the CLEVELAND CONVENTION AND VISITORS BUREAU who used the slogan for a tourism campaign in early 1980. The campaign included a billboard near CLEVELAND HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT saying, “Welcome to America’s North Coast!” It also included newspaper and magazine ads, a jingle, and merchandise. The nickname was embraced by local businesses and media alike throughout the 1980s. In 1987, the newly developed lakefront area was named “NORTH COAST HARBOR” after the name won The PLAIN DEALER naming contest. The official marketing campaign faded away in the early 1990s.

Around the same time “America’s North Coast” was becoming popular, The PLAIN DEALER also put forth the slogan “Cleveland is a Plum.” The Plain Dealer’s Thomas Vail and Alex Machaskee created the slogan for the 1981 NEW CLEVELAND CAMPAIGN. The slogan played off of the expression of something being plum or “something superior or very desirable” as defined by Merriam-Webster Dictionary as well as to play off of New York’s branding as the “Big Apple.” The slogan was first introduced to a Cleveland audience at a May 1981 Cleveland Indians (see CLEVELAND GUARDIANS) baseball game when Mayor George Voinovich (see MAYORAL ADMINISTRATION OF GEORGE V. VOINOVICH) made the first pitch with a plum. “New York may be the Big Apple, but Cleveland is a Plum” bumper stickers were given out to Plain Dealer subscribers. Buttons, t-shirts, and more were given out in public places such as Cleveland Indians games. Contests and events were based on the slogan including a limerick contest, an ice skating show, and a concert called the Cleveland Plum Festival. The campaign was supported by businesses, sport teams, and local groups such as the Opera League. The campaign slowed to a stop around the mid-1980s.

Although Cleveland supported the rise of ROCK ‘N’ ROLL throughout its beginnings in the late 1940s, the city did not fully receive the credit as the “Rock’n’Roll Capital of the World” until it won the bid to build THE ROCK AND ROLL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM in May 1986. Cleveland was first given the nickname, “The Rock’n’Roll Capital of the World,” in 1972 by Billy Bass, WMMS program director. Bass credited the city after reading The Sound of the City—The Rise of Rock & Roll by Charlie Gillett who attributed the naming of the rock’n’roll genre to Clevelanders LEO MINTZ and ALAN FREED in the late 1940s. Mintz, owner of Record Rendezvous in Cleveland, noticed white customers enjoying Black rhythm & blues albums in his store and decided to rebrand the genre to rock ‘n’ roll to change the racial perception of the music. The term “rock’n’roll” was originally in blues songs to infer sexual intercourse dating back to the 1920s. Mintz convinced Freed, a disc jockey for WAKR-AM in Akron, to play rock ‘n’ roll music on the radio. Freed popularized the phrase “rock ‘n’ roll” for his radio program "The Moondog Rock & Roll House Party," on station WJW-AM (see WRMR). Freed’s event, the "Moondog Coronation Ball," held at the CLEVELAND ARENA in March 1952 was the first rock ‘n’ roll concert. Mintz and Freed’s contribution to the music genre served as the centerpiece of the bid to build The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland. The museum opened in September 1995 near the lakefront, and Cleveland has been since known as “The Rock ‘n’ Roll Capital of the World.”

Inspired by Cleveland’s legacy of ROCK ‘N’ ROLL, British rockstar Ian Hunter released the city’s anthem “Cleveland Rocks” in his 1979 album You’re Never Alone with a Schizophrenic. The song begins with a sound byte from Alan Freed’s radio show that made the term “rock’n’roll” famous. While the song was initially released as “England Rocks,” Hunter wrote the song about Cleveland. A cover of the song was done in 1997 by the band The Presidents of the United States as the theme song for The Drew Carey Show. The song contributed to Cleveland’s momentum to being recognized as “The Rock’n’Roll Capital of the World” by being the unofficial anthem and slogan for the city’s bid for THE ROCK AND ROLL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM. One 1985 PLAIN DEALER article on the bid for the museum was titled “Cleveland Rocks!” The song “Cleveland Rocks” remains relevant in 2022 by being played at local events, particularly sporting events. The slogan “Cleveland Rocks” also regularly appears in the city’s media including music events and t-shirts.

Locally-Made Nicknames, 1990s-2010s

While previous decades of Cleveland slogans were largely created by boosters and organizations who sought to place the city in a more positive light, between the 1990s and 2022, more nicknames and slogans emerged from the populace which were then picked up by mainstream media. Some of the most popular nicknames of this era came from abbreviated synonyms for the city, such as “216” and “CLE,” as well as a variation of spelling Cleveland, such as “The Land” and “C-Town.” The later names originated from the intersection of Cleveland’s black community with the emerging hip-hop, rap scene of the 1990s. Other slogans emerged from popular culture of the 2000s.

“The Land” was used in the 1990s hip-hop and rap community, and was popularized by Bone Thugs-N-Harmony’s 1995 album E. 1999 Eternal where “The Land” was featured in the song “East 1999,” among other references to Cleveland. Ever since, “The Land” was used in the hip-hop and rap genre until the nickname made it into mainstream media around 2015 when CLEVELAND CAVALIERS’ basketball player LeBron James started using the nickname on social media and named his Nike-branded sneaker “The Land.” In the same year, popular rap artist Machine Gun Kelly used the nickname in the lyrics “I’m from The Land, Till I Die” to show his pride in Cleveland in his song “Till I Die.” The Land has been regularly used for Cleveland Cavaliers and the “This is Cleveland” campaign.

“C-Town” was also popularized in the 1990s rap and hip-hop scene, but the nickname was sometimes used in the context of music from the 1960s through the 1980s. This included a local 1980s band called The C-Town Four, a quote in a break-dancing and rap article from 1984, and a reference in a rock’n’roll article from 1987. Hip-hop artists such as Kurupt and Jay-Z in the late-1990s have used “C-Town” in interviews and concerts to refer to Cleveland. In 1999, R&B group Smooth Approach released the song "C-Town Here Comes the Browns" about the CLEVELAND BROWNS football team. In 2007, the hip-hop and rap artists Bone Thugs-N-Harmony and Twista released the song “C-Town” about Cleveland and Chicago. While less common than “C-Town,” “C-Land” was also sometimes used, such as Bone Thugs-N-Harmony’s 2000 song “C Land I.A.” “C-Town” was further adopted into mainstream media around the early 2000s, appearing in PLAIN DEALER sports articles.

The cultural use of 216 or “The 216” has mixed origins because of its initial utility as an area code. The 216 area code was assigned to Cleveland and surrounding suburbs in 1947 through the Bell System. Throughout the first decades of area codes, 216 was usually referenced only in the context of phone calls. One exception was the “216 Club” at the HOLLENDEN HOTEL, first mentioned in the PLAIN DEALER in 1952, which was a high-end spot for drinks and music performances. Around the 1990s and early 2000s, 216 started to be referenced outside the context of making phone calls and became a synonym for “Cleveland” or “Greater Cleveland” within popular culture. In the 2000s, “The 216” was another nickname for Cleveland in the hip-hop and rap community. Around the same time, the small business, craft retail community frequently used the nickname for events and initiatives to support local Cleveland artists and small-business owners such as “Made in the 216” and “Shop the 216.” Cleveland Indians (see CLEVELAND GUARDIANS) baseball player Nick Swisher used the nickname “216” in interviews and wore shoes with “216” and the Cleveland skyline during the 2014 season.

Similarly to the 216 nickname, the “CLE” nickname came from the 3-digit International Air Transport Association (IATA) airport code for CLEVELAND-HOPKINS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT. The use of the airport code in popular culture likely stemmed from the “CLE: Going Places” (pronounced C-L-E) slogan and marketing campaign by Cleveland Hopkins International Airport in 2006. The abbreviation now appears regularly in city culture including events and organizations. This includes LESBIAN/GAY COMMUNITY SERVICE CENTER OF GREATER CLEVELAND’s yearly LGBTQ PRIDE IN CLEVELAND event, rebranded in 2016 as “Pride in the CLE,” and the popular CLE Clothing Co. retail stores founded in 2008.

The most popular nicknames for Cleveland in 2022 are “216,” “CLE,” and “The Land.” All three appear in organization names, events, media references, t-shirt designs, and social media hashtags such as #ThisIsCLE from the 2014 Destination Cleveland “This is Cleveland” campaign to encourage social media posts of the city. “C-Town” has continued in 2022 to be used in the media to reference Cleveland, mainly in the music industry, as well as adopted for the names of local businesses and organizations centered around music and art.

While not an immensely popular slogan, the “Flee to the Cleve” slogan was briefly popular in 2007 when the NBC television show 30 Rock coined the phrase. In the episode, the main character, played by Tina Fey, goes on a brief vacation to Cleveland to escape the hustle of New York and sees the positive elements of Cleveland in a brief montage. While the episode was upbeat on Cleveland, the episode was praising Cleveland as a parody, as noted in one quote, "If the whole world moved to their favorite vacation spots, then the whole world would live in Hawaii and Italy and Cleveland." When Fey’s character returns to New York, her boss, played by Alec Baldwin, remarks, “We’d all like to flee to the Cleve.”

Other Cleveland slogans from popular culture of the 2000s derived from the infamous and comedic 2009 Hastily Made Cleveland Tourism Video: 2nd Attempt made by local comedian Mike Polk. The upbeat, catchy tune of the video created quotable phrases referencing pieces of Cleveland’s history. “See our river that catches on fire” alluded to the phrases associated with the 1969 CUYAHOGA RIVER FIRE. “At least we’re not Detroit” concluded the video, which alluded to the rivalry between Cleveland and Detroit stemming back to the sports rivalries of the 1940s and, more likely, the close distance and similarities between the two rustbelt cities. The video went viral for its sarcastically upbeat tone and devastating critiques of Cleveland, which threw a spotlight on Cleveland’s self-deprecating humor as well as its history of economic struggle.

Marketing Cleveland, Part 3, 2000s-2022

Official Marketing campaigns for Cleveland have continued into the 2000s through 2022, all of them promoting Cleveland in more authentic ways that speak more to locals than in the past and aspire to improve Cleveland in multiple ways. The “Believe in Cleveland” slogan sought to show the positive developments in Cleveland to convince the populace to believe in the future of the city. The “Green City on a Blue Lake” slogan and initiative sought to improve the environment in Cleveland, particularly on the lakefront. Finally, the “This is Cleveland” slogan and campaign sought to highlight Cleveland in authentic ways and bring a better perception of the city to a younger demographic. All of these campaigns seek to bring about a perception change in Cleveland that are better grounded efforts to improve the city.

The “Believe in Cleveland” slogan, first popularized by the mayoral campaign for Carl Stokes, was revived by The PLAIN DEALER’s Alex Machaskee and Stern Advertising’s Bill Stern in 2005. The slogan appeared on merchandise, billboards, and media throughout Cleveland to counter the negative perceptions of the city. The campaign featured local public figures discussing the positive developments in Cleveland during the mid to late 2000s including efforts to revitalize struggling areas. The campaign faded out within years of its release.

“A Green City on a Blue Lake” was coined by David Beach, head of EcoCity Cleveland in 2004. Beach said to The PLAIN DEALER, “Just imagine if people around the world had an image of Cleveland as the green city on a blue lake. It has to be more than just a marketing slogan, it has to be more than a brand… that we are organizing ourselves according to principles that protect water, that we think of ourselves as a green city.” Beach went on to discuss how Lake Erie was Cleveland’s greatest asset and young people want to live near the water in a sustainable city. The phrase then became the slogan for the City of Cleveland’s 2009 Sustainable Cleveland initiative which aspired to make Cleveland “a Green City on a Blue Lake” by 2019. The idyllic imagery of this slogan directly addressed the long-lingering image of the Cuyahoga River fires. Post-2019, the continuing initiative strives “to build economic, social, and environmental well-being for all,” according to its website.

Destination Cleveland, formerly the CONVENTION AND VISITORS BUREAU OF GREATER CLEVELAND, INC. and Positively Cleveland, launched the “This is Cleveland” marketing campaign in 2014 with the ThisIsCleveland.com website. The campaign, still in use in 2022, seeks to boost local pride and advertise Cleveland as a tourist destination for a younger demographic who are less affected by Cleveland’s history of negative press. The focal points of “This is Cleveland” campaign are its interactive website, social media including the hashtag #ThisIsCLE, and physical branding around the city including the Cleveland script signs and other photo opportunities. The giant Cleveland script signs were installed around the most photogenic parts of the city starting with the first three in 2016 with a total of 6 as of 2020.

The Sports Comeback Narrative, 2016 NBA Finals

Cleveland sports have always influenced the city’s level of pride. The CLEVELAND CAVALIERS overcoming the 3-1 game deficit in the 2016 NBA Finals against the favored Golden State Warriors generated positive feelings in the region that would further reinforce Cleveland’s “You’ve Got to Be Tough!” mentality and a concrete reason for pride in Cleveland. Since his NBA draft to the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2003, Lebron James, basketball legend from Akron, played a huge role in influencing the Cleveland sports narrative. Cleveland’s pride took a hit when James announced in 2010, in a live ESPN broadcast known as “The Decision,” that he was leaving the Cleveland Cavaliers to play for the Miami Heat. James returned to the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2014 by posting an open letter on the Sports Illustrated website that concluded with, “In Northeast Ohio, nothing is given. Everything is earned. You work for what you have. I’m ready to accept the challenge. I’m coming home.” The phrase, “In Northeast Ohio, nothing is given. Everything is earned,” struck a prideful nerve in the region that echoes Daffy Dan’s iconic t-shirt slogan “Cleveland: You’ve Got to Be Tough!” James coming back to the city and the resulting NBA Finals victory had led Clevelanders to embrace the inspirational phrase and the message behind it.

“Believeland” was a popular nickname during the 2016 NBA Finals that goes back to the mid-1990s and perhaps earlier. “Believeland,” the hopeful message for Cleveland sports, first appeared in The PLAIN DEALER in 1995 as a sign a fan was holding at a Cleveland Indians (see CLEVELAND GUARDIANS) baseball game. The nickname gained prominence in Cleveland sports in 2007 when the CLEVELAND BROWNS created “Believeland” t-shirts. In 2016, ESPN’s 30-for-30 documentary series featured Believeland. The documentary highlighted the unrelenting hope of Cleveland sports fans despite over a half-century-long drought of major sport titles. Directed by Andy Billman, Believeland was aired on television on 14 May 2016, just a month before the CLEVELAND CAVALIERS’ 2016 NBA Finals victory. The documentary ending was rewritten and released on 30 June 2016 to include the victory and bring the Cleveland sports-drought narrative full-circle. While winning the NBA Finals did not fix any socioeconomic problems, it gave Clevelanders a reason to believe in the city. The good feelings about the city since 2016 and the positive national attention it attracted was a tangible piece of the comeback narrative that boosters have been trying to create since World War II.

Modern Relevance of Nicknames and Slogans

Cleveland slogans and nicknames derived from two very different sources in the 20th century and into the 21st century. Official marketing and advertising initiatives with specific ends were challenged by locally-derived nicknames, such as “The Best Location in the Nation” and then “Mistake on the Lake.” Subsequent campaigns show how these official and locally-sourced nicknames and slogans have continually been at odds with one another. Locally-derived nicknames and slogans generally align with the feelings and beliefs of the local populace. While the nicknames and slogans generated from boosters all clearly have an agenda to positively promote Cleveland, more recent local campaigns show an increasing awareness of the need to pay attention to the ideas and feelings of the general population to be successful. Over time, Cleveland boosters have learned that campaigns prevail when either the local populace is the original source of the nickname or a message that local populace can agree with, or are at least neutral towards.

The Cleveland nicknames and slogans that remain relevant in 2022 are nicknames and slogans that are locally sourced and represent Cleveland authentically. They are classic, non-divisive, and represent a broad spectrum of origins. CLE, 216, The Land, C-Town, and The North Coast all fit in this model, as do other slogans. “Cleveland Rocks,” both the Ian Hunter song and the slogan, strongly reflects the area’s pride in its role in popularizing ROCK ‘N’ ROLL. “You’ve Got to Be Tough” represents Cleveland’s history of hardship as a rustbelt city and the need for thicker skin to be from the region. Cleveland-area sports fans felt immense pride in bringing home the title “NBA Champions” in 2016 because it was hard-earned, wrapped in the spirit of believing, and seemed to be an antidote to the community’s reputation as a rustbelt city that had endured possibly some of the worst press of any American city in the 1970s. The locally derived and earned nicknames and slogans for Cleveland, in large part, has made Clevelanders immune to the over-the-top marketing campaigns of the past.

Katie Kuckelheim

Last Updated: 2/27/2023

View Cleveland Tourism Videos at Hagley.org

View "Cleveland Sixth City" Image at Cleveland Memory

View "1952 Cuyahoga River Fire" Image at Cleveland Memory

View Image at Cleveland Historical

"Best Location in The Nation..?" Cleveland Call and Post (1934-1962), Dec 19, 1953.

Dawson, Lois. "The Mistake on the Lake?" Call and Post (1962-1982), May 2, 1964.

Hatcher, Harlan. The Western Reserve: The Story of New Connecticut in Ohio. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press in cooperation with the Western Reserve Historical Society, 1991.

May, Jon D. “Erie.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Accessed on April 18, 2022.

"Mets Campaign for Stokes." Call and Post (1962-1982), Nov 04, 1967, City edition.

Miller, Carol Poh and Robbert A. Wheeler. Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796-1996, Second Edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Ohio General Assembly. An Act to incorporate the village of Cleveland in the county of Cuyahoga. Ohio History Connection, SAS 577 Box 4. Columbus, Ohio, 23 December 1814.

Rose, William Ganson. Cleveland: The Making of a City. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1990.

Souther, J. Mark. Believing in Cleveland: Managing Decline in the Best Location in the Nation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017.

Souther, J. Mark. “‘The Best Things in Life Are Here’ in ‘The Mistake on the Lake’: Narratives of Decline and Renewal in Cleveland.” JOURNAL OF URBAN HISTORY 41, no. 6 (November 1, 2015): 1091–1117.

“Sustainable Cleveland.” Sustainable Cleveland. Accessed on April 18, 2022.

![Photo caption reads “George Voinovich throws out the first plum at an Indians-Yankees game, launching a campaign [Cleveland is a Plum] to sweeten Cleveland’s image nationally.” Courtesy of The Plain Dealer.](/ech/sites/default/files/2022-05/Voinovich%20Plum.jpg)