Interview with Ellen Hargis by Anna O’Connell

What brought you to historical performance practice? What interested you about it?

Well, I started out as an instrumentalist. I was playing in my college collegium, pretty much for fun. I thought I might want to be a choral conductor someday, but I also thought I might want to be a French teacher. And I was just doing my basic courses as a freshman when I began playing recorder in the Collegium and got completely fascinated by other Renaissance instruments, baroque instruments, and then eventually singing. And long story short, by the time I finished university, I was 99% in the singing world. I found that Historical Performance really complemented my equally strong interest in languages, because the repertoire is so text-based. So that was a great way to have my cake, and eat it too.

Where did you do your Undergraduate?

I did my undergrad at Oakland University, which at the time, was the only place in the States where you could study early music as an undergraduate.

After you were at Oakland, what projects were you working on? Did you continue your education?

I started to work professionally at some level right away, primarily as a singer (very occasionally playing instruments), but mostly I was singing and doing a lot of chamber music, and eventually doing more baroque solo work with orchestras. There was a time when I returned to my interest in languages and began a graduate program in historical linguistics at the University of Michigan. I never completed the degree because I started to get more singing work and I felt that I should take that opportunity when it was presented to me. But the interest in historical linguistics has never left me and I’ve never regretted one moment that I spent studying that material, because it has served me well. Now, I do a lot of translating of cantatas and songs, first by just doing my own translations for my programs. When I began to feel capable of doing that kind of work in French and Italian. I began to be asked to do translations of librettos for opera productions. So it was a great complement to singing and a wonderful way to learn the score.

In this production of Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie, you are the stage director. How long have you been directing baroque operas, and do you specifically direct opera from the baroque period, or others as well?

No, baroque opera has been, by choice, my niche area. I think I started, maybe 10 or 12 years ago. A friend of mine was the general producer of a performance of Monteverdi’s Orfeo for a humanities festival in Canada, and he said, “Would you like to direct Orfeo, please say yes!” And so [chuckling] I dutifully said, “Yes,” figuring I’d just jump in with both feet. So that was my first experience, and it really hooked me. It’s a fantastic job, this mis en scène, this putting the staging together, because it involves music, it involves language, and it involves movement, all of which I’m really interested in. I’m a terrible dancer, though I’ve taken baroque dance, and I’ve studied baroque gesture. I’m fine at gesture, but the feet never cooperated. So staging operas was a way of really investing myself in what I believe is the key to unlocking this repertoire, which is an aesthetic consistence between physicality, sound, and visuals.

In Hippolyte et Aricie, where does your inspiration for this opera staging come from, and what resources have you found along the way that have helped in that process?

It’s an interesting piece. It was tremendously popular in its own time and had many revivals over several decades, and the piece was changed each time it was revived. It’s interesting to see what survived all those changes, and what people saw as the strength of the piece. It’s fairly standard stuff in terms of the struggle between humans and the gods, between virtue and desire, and love is at the center of everything with all of its ramifications: jealousy, vengeance, misunderstandings, all of those kinds of things.

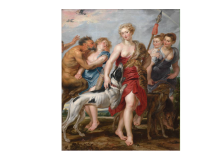

I take a lot of my inspiration for the staging of this work from art. There are lots and lots of pictures of the characters in this opera that were painted contemporaneously in the mid-eighteenth century. So we have loads of pictures of the goddess Diana, who was such a popular character that many noble ladies of the period had themselves painted in the guise of Diane. She’s wearing animal furs, and she’s carrying a spear. This sort of fierce, independent image is one that I thought was interesting for this opera, in an opera full of strong women.

We also have our antagonist, Phaedre, who is famous from Greek tragedy. In fact, a play written by Racine on the story of Phaedre, was the basis of the libretto for this opera. Her struggle is very much at the center of the opera, the personal struggle of this woman who is at once in love with her stepson and horrified at her own transgression of social norms. She’s another very interesting character that we have lots of pictures of, as well as Theseus, a mythological hero, and his son, Hippolytus, who is most famous for his hideous death, which thankfully, we don’t have to see in this opera! So, I looked at a lot of paintings for ideas about how to see how to recreate the pictures on the stage, but I read the play of Racine for ideas about the psychology of Phaedre.. Then I looked to the libretto, of course, for further inspiration for what the tensions are between the characters, and that really translates to where they are on the stage.

What makes this music exciting?

That’s a good question. I think this is an odd thing for a singer to say, but what makes Rameau exciting is the orchestra. The orchestrations are extravagant. They are at least as dramatic as anything in the voice parts. When you compare Rameau, say, to Lully, which is a comparison a lot of people like to draw, I think they’re equally wonderful writers for the voice. But Lully is much more conventional when it comes to the orchestration, and Rameau just pulls out all the stops. There are sound effects in the orchestra, there are harmonies which you can scarcely believe are really true on the page because they’re so exotic. Plus, the number of instruments in the orchestra is fantastic. We have oboes and bassoons, but also horns, also trumpets, and harpsicords, theorbo, all kinds of strings, and “folky” instruments as well.

That said, this is not to slight the singers, because the vocal writing is staggering! It’s highly dramatic, highly evocative; and sometimes playful. One of the things about this opera which is going to make it accessible to everybody whether they like “opera” or not, is this structure which involves drama relieved by something called Divertissements, which are little diversions plopped in the middle of every act. So just when you think you can’t take any more tragedy, you get a scene with dancing sailors, or dancing trees, and animals, or shepherdesses who sing about love. So there’s this wonderful entertainment quality which, of course, was demanded by the rich patrons who were seeing these operas, or paying for their production. But today, it also helps us enjoy ourselves through what is essentially a very sad story; though it all ends well at the finale.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about the opera?

One of the interesting things about this production is that for this anniversary of the collaboration between CIM and Case Western Reserve University, the two schools were decided to do a historically informed production of a baroque opera. We’re not, as is so often done with early opera, plopping this into Central America in a drug war, or into a high rise in New York, starring the Trumps and the Clintons. This is really going to be produced with historical performance practice. So we have a set designer and a costume designer who are working very hard to create the kinds of costumes and sets they would have had in a baroque theater. Similarly, we are using baroque instruments, we are doing baroque dance, and our singers are employing the conventions of vocal ornamentation, stage movement and baroque gesture. This brings everything into an aesthetic whole. They just help us to have a nicely blended picture of the whole thing. It’s a been a great learning experience for the performers. For the audience, it just means a really magical evening of opera, like they may not have seen it before.

What advice—as many of our singers and instrumentalists are not yet fully fluent in the languages of baroque opera, gesture, performance—what advice would you offer, words of encouragement in order to help them along that path?

Well, for singers, certainly start with the text. Find good translations of the poetry. There are good books that can help you understand the rudiments of French declamation, which is at the root of how the text is set to music. Once you understand how it was constructed in the first place, it suddenly makes so much more sense. There’s a lot on the page to help you, because the French were so careful about notating every little detail. It can be a little daunting to look at the score, because it’s full of little signs and additions and notes and it seems like a lot to wade through. But in fact, it’s all there a kind of code, to help with the interpretation. To learn historical performance in general, if you’re not lucky enough to be enrolled in an HPP program like the one here at CWRU, there are a lot of summer programs where you can go and immerse yourself in early music for one or two weeks, working with experts in the field. There are some specifically for opera, there are some that are for instrumental work, some that mix them both. And I think they all have a great function, and are a great aid in getting you familiar with the style, and also helping you establishing a network of resources and people who can be resources for you if you continue to explore.

Lastly, who has been a mentor for you? And what is something they have said, that sticks with you to this day?

I think my mentor as a stage director is definitely the man who is in Stage Director in Residence for the Boston Early Music Festival, Gilbert Blin. I met him while I was singing the lead romantic role in Lully’s Thésée. Through working with him, I learned so many keys to working with text and bringing it to life on the stage as an actress, that it really opened my mind to what it meant to work as an actress in an opera. And I have been his assistant now for six productions at the Boston Early Music Festival, and I learn something new every time we work together. He’s just got one of these great intellects that is also multidisciplinary, and he really understands how to connect the dots between the various disciplines to make something that is compelling on the stage. And I think his message to me that has really stuck with me, over and over, is that we have to get to the heart of the emotions of the characters we portray. We have to really understand and love, and have sympathy for the characters, in order to bring them to the stage in a stylized way, and not have them appear two-dimensional. That third dimension comes from the artist really understanding their text, really understanding their feelings of their character, and expressing it through this language of the baroque.

I think that’s all we have time for today. Thanks so much!