The Science Behind Making Healthy Decisions

By Kristin Ohlson

“Lack of knowledge is not the problem,” says Shirley Moore, PhD, RN, FAAN, associate dean of research and the Edward J. and Louise Mellen Professor at the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing. “It’s not that people don’t know what happens when they smoke or that they don’t know the importance of diet and exercise. What we need to figure out is how they process that information to identify the factors that help them decide to take the right actions.”

To that end, Moore and collaborators from the Self-Management Advancement through Research and Translation (SMART) Center—where Moore is the principal investigator and director—have launched eight pilot research studies to investigate the connection between behavior and changes in the brain. While the studies are small—with around 30 patients in each—and the funding modest, the team from the School of Nursing and its Neuroscience Lab, the College of Arts and Sciences’ Brain, Mind & Consciousness Laboratory, and the School of Medicine’s Case Center for Imaging Research hopes this unique initiative will provide insights that lead to larger studies.

These efforts build on the SMART Center’s work over the past decade. Created in 2007 with a $2.23 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Nursing Research, the Center focused its research on the science of self-management by designing and testing tools and strategies for individuals and families that improve health. The Center received an additional $2.35 million NIH grant to dive deeper into this work by examining the neurologic basis for positive health behavior change.

The impact of the knowledge gleaned from this research could be huge. Around 80 percent of health care is self delivered—individually or with family assistance. We are responsible for taking our medications, monitoring our health, engaging clinicians, and reporting symptoms, as well as making critical daily decisions about food, exercise, sleep, stress, and danger. Figuring out how to help patients make healthy choices as they discharge this responsibility is, as Moore says, “the holy grail of health science” and could dramatically impact both the effectiveness and cost of care.

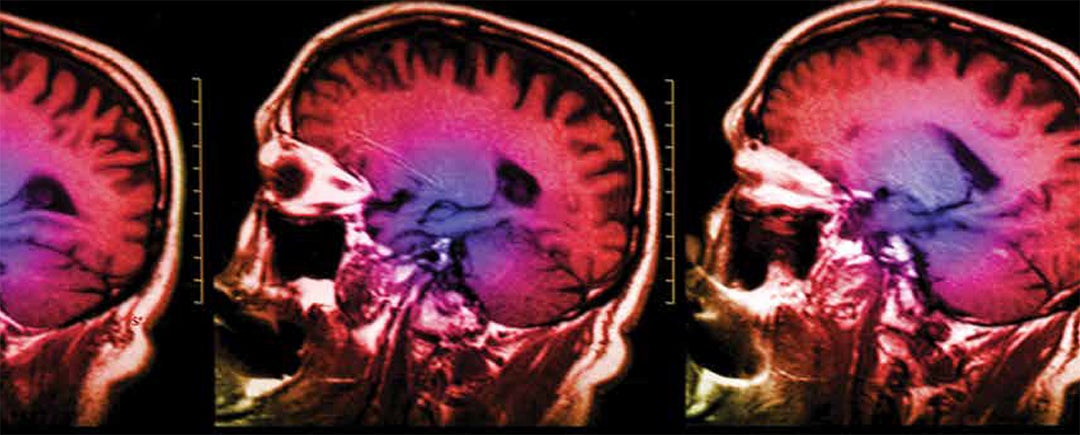

Each pilot study targets a different population that is either dealing with or at risk for a chronic illness. Within each study, participants are introduced to one or more self-management interventions and provided with basic information on how to control their illness. Before the intervention, patients undergo a functional MRI to establish baseline activity in two cortical networks that affect behavior: the default mode network (DMN), the more emotional and social part of our brains, and the task positive network (TPN), the analytical part of our brains.

“…My goal is to help parents and early-adolescent kids build the strength of their relationship and improve trust before the kids become skeptical.”

After the intervention is completed, the participants return for a second brain scan to see how activity in these two networks—demonstrated by increased blood flow—has changed. The studies will examine this change in brain activity with the participants’ behavior change. The working hypothesis is that our emotional network needs to be de-activated before our analytical, task-oriented network can be engaged to make changes in behavior.The impetus for this series of studies came from research showing that managers in the world of business who can switch rapidly between the DMN and TPN networks were more likely to make plans and take action on them.

“The whole idea of the SMART Center is to understand brain mechanisms that are involved in behavior change,” says Michael Decker, PhD, RN, RRT, Diplomate ABSM, associate professor of nursing and leader of the Center’s Neuroscience Core. “We are looking for patterns of brain activation that parallel changes in behavior. Nursing is just beginning to utilize neuroimaging to see how interventions affect brain functioning.”

The brain scans will also map neural pathways andcapture the unique anatomy of each participant’s brain.

“This research offers the opportunity to connect the basicanatomy and functional information from neuroimaging with behavioral changes,” says Chris Flask, PhD, associateprofessor and scientific director of the Case Center for Imaging Research. “My role is to figure out how we can bestuse the magnetic resonance technology and to develop new technologies if needed to sensitively track these changes.”

Six of the eight pilot studies have been designed by an early-career nurse scientist.

“We are looking for patterns of brain activation that parallel changes in behavior. Nursing is just beginning to utilize neuroimaging to see how interventions affect brain functioning.”

One of the pilots examines the impact of trust on health between children who are at risk for obesity and their parents. This study is designed by postdoctoral fellow Heather Hardin, PhD, RN, based on insights from her previous research. She had found that adolescents who reported higher levels of trust had healthier lifestyle behaviors. Knowing that the key to adolescent weight management lies in the home, and since parents contro lmost of their children’s diet and lifestyle choices, she wondered if building greater trust between parents andadolescents would lead to better weight management.

“At around the age of 14, kids become more skeptical and mistrustful,” Hardin explains. “They have cognitive abilities they didn’t have before and suddenly realize the world is very relative and that there are gray areas. They may have been taught X is always right and Y is always wrong, but they begin to realize this might not always be true. My goal is to help parents and early-adolescent kids build the strength of their relationship and improve trust before the kids become skeptical.”

Hardin’s study will assign 30 parent-child dyads to one of two groups. One will participate in eight weekly 90-minute trust-building sessions based on Rotenberg’s Framework of Interpersonal Trust, which focuses on honesty, reliability and emotional connection. The other group will receive enhanced usual care – a single dietary and physical activity counseling session and eight weekly follow-up phone calls.

In another study, assistant professor Valerie Boebel Toly, PhD, RN, CPNP is presenting two interventions to a population she knows well: caregivers of children with complex, chronic medical conditions that require medical technology such as mechanical ventilation or feeding tubes.

Toly has already tried the resourcefulness training in another study with great success, but she suspects that the combination may be even more helpful.

“I worked as a home health nurse with these families years ago, and the experience never left me,” says Toly. “The care for these children is so complex, with a number of therapies and treatments and doctor visits, and the caregivers do it 24-7, sometimes for years. What struck me was not only their stress but the fact that some families floundered while some thrived, even with nearly identical circumstances.”

In Toly’s pilot, thirty such caregivers will be randomly divided into two groups. One group will be given an intervention called ReMind, a package of daily mindfulness meditation delivered via smart phone along with individual training in eight resourcefulness skills, regular journaling about their experience with the skills, and weekly followups.The other group will only receive the mindfulness meditation app. Toly has already tested the resourcefulness training in another study with promising results, but she suspects that the combination may be even more helpful.

Across all eight studies, investigators will employ common data elements to ensure that they are all evaluating participants in the same way and can aggregate results.

“We want to make sure we’re measuring the samethings across different populations,” says pilot studies core leader Carol Musil, PhD, RN, FAAN, FGSA, the Marvin E. and Ruth Durr Denekas Professor of Nursing. “For example, we have to measure similar outcomes among adolescents, among people with AIDS, and among adults with hypertension.”

All participants must be cognitively intact. All are evaluated for depression and stress, the latter measured both in the hair and blood. Their ability to solve problems—executive function—is recorded, as well as their level of self efficacy, or the belief that they can be successful at something.Investigators record how much social support they have and gauge their capacity for compassion—not just for others, but also for themselves, especially when they need to forgive their own failures. Investigators will track their ability to decenter—to pull away from a situation and assess it with some objectivity. These common elements will likely give researchers a profile of the characteristics that influence self-management across all studies. But the breakthrough of this initiative is it will link all of the factors that nurses and other health professionals typically gather from patients – from their ability to regulateemotions to their level of compliance with health care—to the anatomy and function of the brain.

“We now have a way to look directly at the organ that determines whether and how you can change your behavior,” says Anthony Jack, PhD, associate professor of philosophy and leader of the Brain, Mind & Consciousness Laboratory. “We are not merely looking at the brain but are getting the kind of information that eventually will revolutionize our ability to intervene and help people.”