Making the Nursing Profession More Accessible to Everyone

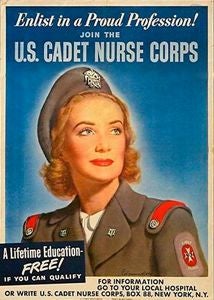

It’s been called “the most significant nursing legislation in our time” and played a significant role in supporting the U.S. war effort during the final years of World War II. The Bolton Act of 1943, sponsored by our school’s namesake and benefactor Frances Payne Bolton, introduced the nation’s U.S. Nurse Cadet Corps and, at the time, was considered the largest experiment in federally subsidized education in the history of the United States.

As a U.S. representative, she saw the need to boost the ranks of nurses for the war. The Bolton Act, enacted on June 15, 1943, accomplished this by appropriating $160 million in federal funds ($65 million in the first year alone) to 1,125 nursing schools all over the country, including those that educated African Americans. It created the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps, which, over the next five years, produced 124,065 graduates out of 169,443 enrollees. The Corps united American nurses from diverse backgrounds to work for a common purpose. By 1945, 85 percent of all nursing students in the country were Cadet Nurses, and the Corps’ funding represented more than half of the entire U.S. Public Health Service budget.

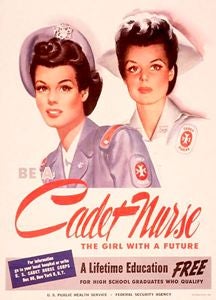

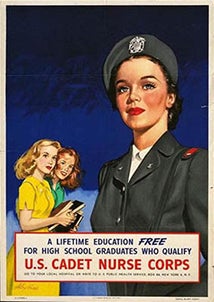

Nursing, Mrs. Bolton declared, was the “number one service for women, not only in a time of war when hundreds of thousands of men’s lives depend upon nursing care, but also in peacetime—for the nurse is not only caring for the sick but also teaching health.” Introducing an unprecedented non-discriminatory clause, the Bolton Act opened up the nursing profession to all women between the ages of 17 to 35 who had completed high school and were in good health. For minority women in particular, the act was their best opportunity to not only receive a nursing education but also to respond to their country’s patriotic call to service at an urgent time in history. With assistance from the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, more than 3,000 African American women answered that call, in addition to 350 Japanese Americans and 40 Native Americans.

All members of the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps received tuition scholarships, monthly stipends and payment of all other education fees, including the cost of books and uniforms. The act “designate[d] student nurses as having answered the call of their country for this vital work” by stipulating only that they complete their education within 30 months and pledge themselves to serve in “military or essential civilian nursing throughout the war.”

Although the Corps’ last cadets graduated in 1948, the Bolton Act had a profound effect on nursing education. The Corps’ emphasis on an academic approach over apprentice-style training led to increases in course offerings and faculty sizes in the ensuing years. The respect and authority that nurses gained via their wartime experiences gave women more opportunities for both undergraduate and postgraduate education, integrated previously white-only institutions and diversified nursing into areas such as convalescent care, public health, pediatrics, tuberculosis and psychiatric care.

As Mrs. Bolton declared in a radio speech for the announcement of the Bolton Act, the program that it created would bring nurse education from “Crude apprenticeship to scientific preparation for a broad and contributive professional career.”