Case Western Reserve University’s School of Dental Medicine has educated several legacy families since its founding in 1892. Perhaps one of the longest-serving is the Cain Family, with roots at the school dating back to 1915. Remarkably, four direct generations of Cain family members have served in dentistry for 121 years, and nine family members attended the dental school.

Family patriarch Henry Oliver Cain graduated from the Cincinnati College of Dental Surgery in 1900, from where six of his brothers-in-law also graduated. Originally from southern Ohio, Dr. Henry Cain is credited with naming the town of Fly, Ohio, while serving as postmaster there and during the tenure of former President William McKinley as Ohio’s governor. Dr. Cain originally wanted to name the town “Cainsville” because of his family name, but this was not allowed due to the cities “Zainsville” and “Painsville” already existing in the state. Allegedly, Dr. Cain said the area was “no bigger than a fly,” thus its name. Following dental school graduation, he moved to Canton, the first industrial city north of the Ohio River. The location was fortuitous for starting Cain & Cain Dentistry, founded in 1915, as the area was growing with people moving from Appalachia to work nearby in the steel mills.

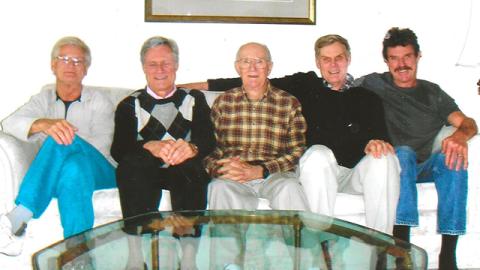

Dr. Henry Cain’s son, Joseph Marion Cain (DEN ’1915), graduated from Western Reserve University School of Dentistry in 1915. He then joined Dr. Henry Oliver Cain in the Canton office. His sons, Charles Cecil Cain (DEN ’42) and WWII veteran and Joseph Henry Cain (DEN ’52), graduated in 1942 and 1952, respectively. Joseph Henry served in the Navy during World War II, where he met his wife, a hygienist and graduate of Forsythe Dental Hygiene in Boston. They married, and four of their five children pursued dentistry, with three sons studying dentistry at Case Western: Joseph Robert Cain (DEN ’73), Paul Cain (DEN ’76) and David Cain (DEN ‘85). (Son Peter attended Columbia University’s dental school, and daughter Nancy earned her bachelor’s and master’s in teaching). Joseph Robert subsequently completed residencies in Maxillofacial Prosthetics and Prosthodontics in Houston and is a professor emeritus from the University of Oklahoma College of Dentistry. Sons Peter, Paul and David each pursued orthodontics, opening their own private practices in Connecticut, New York and California. Their cousin, Lyn Vandevere Bates (DEN ’72), graduated from the dental school in 1972 and opened his own orthodontics practice in Canton, Ohio. Other cousins, Patricia Whitney Hill (DEN ’40), graduated from Western Reserve University School of Dentistry in 1940, and Joseph Park Shai (DEN ’43) graduated in 1943.

Four members of the Cain family served Cain & Cain Dentistry: Henry Oliver, Charles Cecil, Joseph Marion and Joseph Henry, with at least two Cain dentists serving simultaneously. The family practice shuttered its doors in 1993, and the next generation of Cains are pursuing other professional interests. “Over 100 years of the Cain Dental Dynasty is done,” said Dr. Joseph Robert Cain (DEN ’73).

“A number of people over the years said because my brothers and I are fourth-generation dentists, we must have known all along what we wanted. You can watch someone doing dentistry all day long. Until you are doing it yourself, you have no idea what is going on,“ said Dr. Joseph Robert Cain. “I would never try to talk anyone out of going into dentistry. There are many options beyond general practice that can be pursued in the event that general practice is not right for you. I personally found Maxillofacial Prosthetics to be an especially rewarding way to spend my working career.”

Dr. Cain is grateful for his education at the dental school. “I was in a certain place, a door opened, and I chose to go through that door. The first door that opened for me was Western Reserve Dental School. It exposed me to health sciences and dentistry. I was doing things, and if I didn’t like it, I could segue off into something else. There were many good faculty who were good clinicians; they cared about the treatment patients got, and they worked with me and the patients to make sure I got a good education. This is when you could still flunk out of dental school! The fact that they accepted me and introduced me to the profession was the first of many doors that opened and led me to where I am today. When I look back on it, I don’t think I would change anything. There was never a day when I did not want to go to work.”