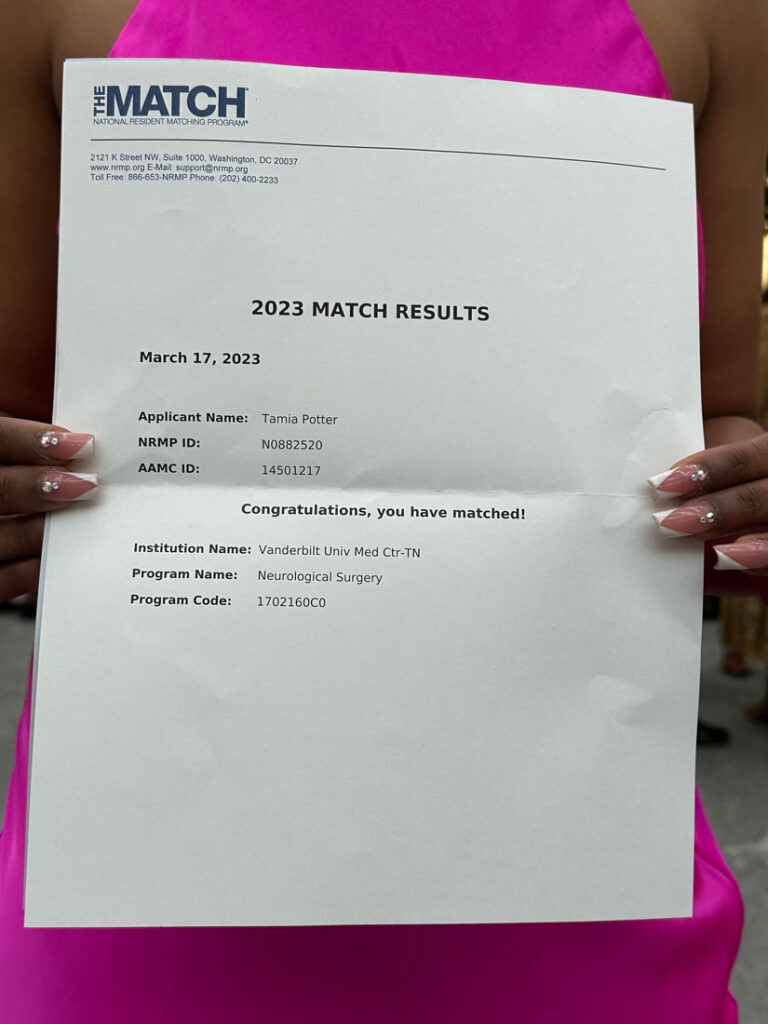

When Tamia Potter opened her envelope at Match Day—the day medical students nationwide learn what residency programs they will join following graduation—she discovered she was one step closer to achieving her goal of becoming a neurosurgeon. She also was among the first to realize she had just made history.

Upon graduation from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in May, Potter will become a neurosurgery resident at Vanderbilt University—and the first Black woman to join the program in the school’s nearly 150-year history.

Only about 5.7% of physicians in the United States identify as Black or African American, according to recent data from the Association of American Medical Colleges. And a 2019 association report showed there are just 33 Black women neurosurgeons in the country.

Potter’s match to Vanderbilt generated news stories nationwide, from outlets such as cleveland.com and News 5 in Cleveland to CNN and Yahoo! News. The stories came within days of her announcement on Twitter, which has more than 500,000 views and counting.

Initially, Potter was gratified, thrilled and relieved to begin the next phase of her training to become a neurosurgeon at a school she selected as her No. 1 choice. Like her peers, she had reached the end of an incredibly competitive process for which she’d been preparing since entering medical school.

The significance of her personal accomplishment hit later.

A lifelong pursuit

“You read about how people make history,” Potter said. “You don’t think that’s going to be you.”

But this was a moment she had been planning for from a young age when her fascination with the human brain and its inner workings first sparked.

“As a child, watching my mom, a nurse, care for patients—I was always questioning why the body works the way it does,” said Potter. “I knew [then] I wanted to learn and understand how the brain and nervous system worked; I wanted to be a neurosurgeon.”

This curiosity led Potter to earn her certified nursing assistant license at age 17, while still in high school. She spent her nights during college working at a nursing home as she earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. Caring for those with dementia only fueled her curiosity to understand and solve the mysteries of illness that plague those with neurological diseases and injuries.

A community of support

According to Potter, the rigor of Case Western Reserve’s medical school curriculum, along with its opportunities to conduct research on neurosurgical trauma and recovery and the depth of clinical exposure at the university’s affiliated hospital systems, not only prepared her for residency but also for a career as a neurosurgeon.

But she stresses the importance of the many mentors who have been just as instrumental throughout medical school.

“It takes a village,” she said.

Emeritus faculty member Robert L. Haynie, MD, and his wife Edweana Robinson, MD, have been part of her village, providing her support and encouragement during the everyday challenges of life as a medical student and being away from her family.

Another of Potter’s mentors, associate professor of neurological surgery Krystal Tomei, MD, introduced her to Tiffany Hodges, MD, one of the first Black women neurosurgeons to work at University Hospitals. Having never met a Black woman neurosurgeon until coming to Cleveland, Potter describes her encounter with Hodges as her point of realization that “this is possible.”

Mentorship from School of Medicine society dean Todd Otteson, MD, and Cleveland Clinic neurosurgeons Pablo Recinos, MD, and Varun Kshettry, MD, has also been crucial in helping Potter to achieve her goals.

“It does take a village to mentor our medical students, and we have amazing, dedicated faculty members who are there for our students to help them achieve their academic goals,” said Lia Logio, vice dean for medical education at the School of Medicine. “Mentorship is at the core of how we as a medical school prepare the next generation of physicians.”

Looking to the future, Potter recognizes her responsibility as a mentor for other students. “I didn’t get here by myself,” she said. “Whoever comes behind me, I want to make sure they have help, too. This field [neurosurgery] is amazing—no one should be boxed out due to a lack of support or resources.”