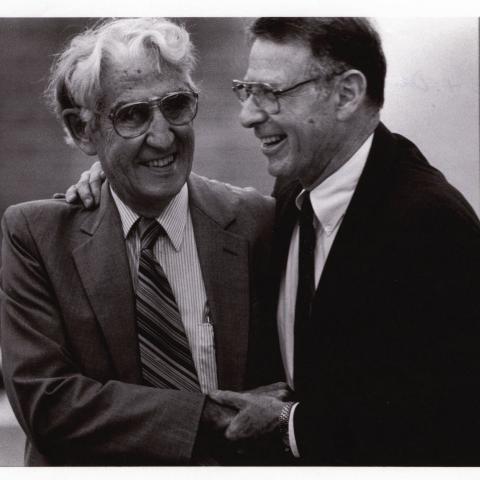

Paul Berg, PhD [GRS'52], Nobel Prize winner and pioneer in the field of genetic engineering, who earned his PhD in biochemistry from Western Reserve University in 1952, died last month.

Berg became the university’s first Nobel Laureate in Chemistry in 1980 when he was awarded the prize “for his fundamental studies of the biochemistry of nucleic acids, with particular regard to recombinant-DNA.” He was one of three scientists to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for work in recombinant DNA in 1980, joining Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger, who were honored for “their contributions concerning the determination of base sequences in nucleic acids.”

His pioneering research on the insertion of DNA from E. coli bacterium into the animal virus SV40 which became the first known instance of recombinant DNA was a milestone in scientific discovery. This discovery launched the field of genetic engineering, resulting in numerous medical advances, including hepatitis vaccines, synthetic insulin and human growth hormone.

His intellectual curiosity is what brought him to Western Reserve University, and it was his experience as a student that solidified his path in academic research.

During his last year as an undergraduate majoring in biochemistry at Pennsylvania State University, Berg became fascinated with emerging radioisotope technology. Most of the literature on the subject, specifically “how compounds labeled with isotopic carbon and/or heavy nitrogen atoms could be tracked during their conversion from foodstuffs to cellular materials,” was authored by Harland Wood at Western Reserve University.

Although he had never heard of Western Reserve University, Berg knew he wanted to go there to continue his studies.

“That was a fortunate choice; in fact, it changed the course of my career,” he shared in his Nobel Prize biography. “Because of its pioneering work in this new field, the department had by the late 1940s become one of the important biochemistry centers in the country. Harland Wood, the department head, was an inspiring scientist and teacher, but he was also devoted to his students and colleagues.”

But when he arrived, Berg learned he would not be a student in Wood’s newly formed biochemistry department as he had anticipated but instead in the clinical biochemistry department.

During this unexpected detour, Berg worked on developing the artificial kidney and learning surgical skills. It wasn’t until Wood approached him and asked if he would be interested in transferring to biochemistry that he could actualize his research ambitions.

It was in the Wood laboratory where Berg could focus on the research that initially drew him to study at Western Reserve.

The opportunity to innovate and make scientific discoveries during his time in the Wood lab solidified his career path in academic research. He abandoned his original plan to pursue a career in the pharmaceutical industry.

Berg’s doctoral thesis illustrated “ the conversion of formic acid, formaldehyde and methanol to the fully reduced state of methyl groups in methionine.” Later, he expanded upon these findings and was among the first to “demonstrate, in vitro, that folic acid and vitamin B12 cofactors participated in these processes”.

After completing his PhD, Berg continued research in Copenhagen and at Washington University in St. Louis. In 1959 he joined Stanford University to help establish a new department of biochemistry and later the Beckman Center for Molecular and Genetic Medicine.

Throughout his career, he was a pioneer and is, most notably, recognized for discovering the utility of recombinant DNA that led to genetic engineering, which is now routine in any biomedical research lab. His contributions continued into the late 1990s, where his laboratory continued to shed light on how DNA repairs itself.

Berg also had a humanistic side and led the way in creating a framework for regulating the use of technology by organizing the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA. Although the conference was held 40 years ago, it serves as a blueprint for a modern-day conference to consider the implications of artificial intelligence.

As an early leader in biotechnology, his vision of bringing the utility power of recombinant DNA to market with an eye towards the open and free sharing of science was realized with DNAX Research Institute. This model allows scientists to continue to publish their work while developing the technologies.

Berg also recognized the greater impact of science could be achieved with collaboration between basic scientists and clinical researchers, prompting him to establish the Beckman Center of Molecular Research in 1985.

As an early leader in biotechnology, his vision of bringing the utility power of recombinant DNA to market with an eye towards the open and free sharing of science was realized with DNAX Research Institute. This model allows scientists to continue to publish their work while developing the technologies.