With a $3.99 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, biomedical engineers from Case Western Reserve University and the University of Chicago will begin testing an implantable device that restores the sense of touch to breast cancer patients after reconstructive surgery.

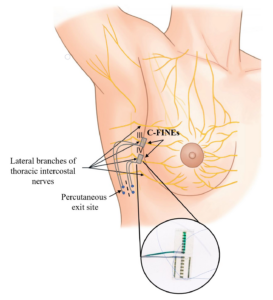

In this project, a medical device called a C-FINE will send touch signals to the nervous system. This type of technology has been used to provide a sense of touch to a prosthetic device after a limb is amputated.

But the study marks the first application of the C-FINE in intercostal nerves, which communicate signals from the breast. Once implanted, the research team will investigate how to stimulate the nerves to create the sense of touch on the breast and how to shape the sensory experience.

“Losing a breast to cancer can be a devastating experience,” said Emily Graczyk, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering, who is leading the work at Case Western Reserve. “In addition to facing the psychological challenges of mastectomy, such as grief and social stigma, breast cancer survivors also have to contend with lifelong numbness and pain that frequently results from having the breasts removed.”

Graczyk and her team have been studying nerve stimulation to restore sensation to people with limb loss and spinal cord injury for more than a decade. They will join their expertise in neuromodulation with the University of Chicago team’s clinical expertise in breast cancer treatment and surgery. The University of Chicago team is led by Stacy Tessler Lindau, professor of obstetrics and gynecology.

The work builds on research by Dustin Tyler, a professor of biomedical engineering at Case Western Reserve and consultant on the NIH project. His vast research has demonstrated that nerve stimulation can recreate the sense of touch for people who have lost limbs.

“We’ve conducted extensive studies over the past decade to understand how to provide useful information to the nerves,” Tyler said. “Because this technology has already shown a positive impact for people with limb amputation, we’re highly optimistic that similar benefits will be possible for breast cancer survivors.”

Clinical trials

To test the device, the team will recruit patients scheduled for a bilateral mastectomy for breast cancer in Chicago. The mastectomy and initial phase of breast reconstruction will occur concurrently with the implantation of the C-FINE device, which wraps around the intercostal nerve branches. Thin, flexible wires will exit the skin under the arm to connect to an external neurostimulation system.

In a lab, the researchers will test the system by sending small electrical signals to the implanted electrodes around the nerves. These electrical signals activate the nerves to create touch sensation. Patients will describe aspects of the sensations, including their location, intensity and how natural it feels. The stimulation can be adjusted to improve the sensations.

In the clinical trial’s initial phase, the devices will be removed when the patient returns for the second phase of reconstructive surgery. But the long-term goal is to create a permanent system patients can use in their daily lives.

The technology is still being developed to create this permanent, fully implanted system for patients to use outside the lab. Researchers at the University of Chicago are creating an implanted flexible sensor, which will be placed beneath the areola and nipple, to detect touches applied to the breast.

The device would then send an electrical output to the neural interfacing system. Future phases of the clinical trial will test the sensor, as well as fully implanted versions of the electronic components, for effects on sensation and pain over longer periods.

“Without sensation in the breast, cancer survivors struggle to know when clothing or people are touching their body, which can be distressing,” Graczyk said. “Imagine hugging your spouse or child and feeling nothing from your chest. The emotional connection could feel muted. We believe nerve stimulation will be able to provide realistic touch sensation to the breast, which will help women find a new sense of normalcy at the end of their fight against breast cancer.”

For more information, contact Patty Zamora at patty.zamora@case.edu.